Aaron's Law: new bill aimed at fixing 'flawed' US hacking legislation

Bipartisan bill named after Aaron Swartz - the internet activist who committed suicide earlier this year

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

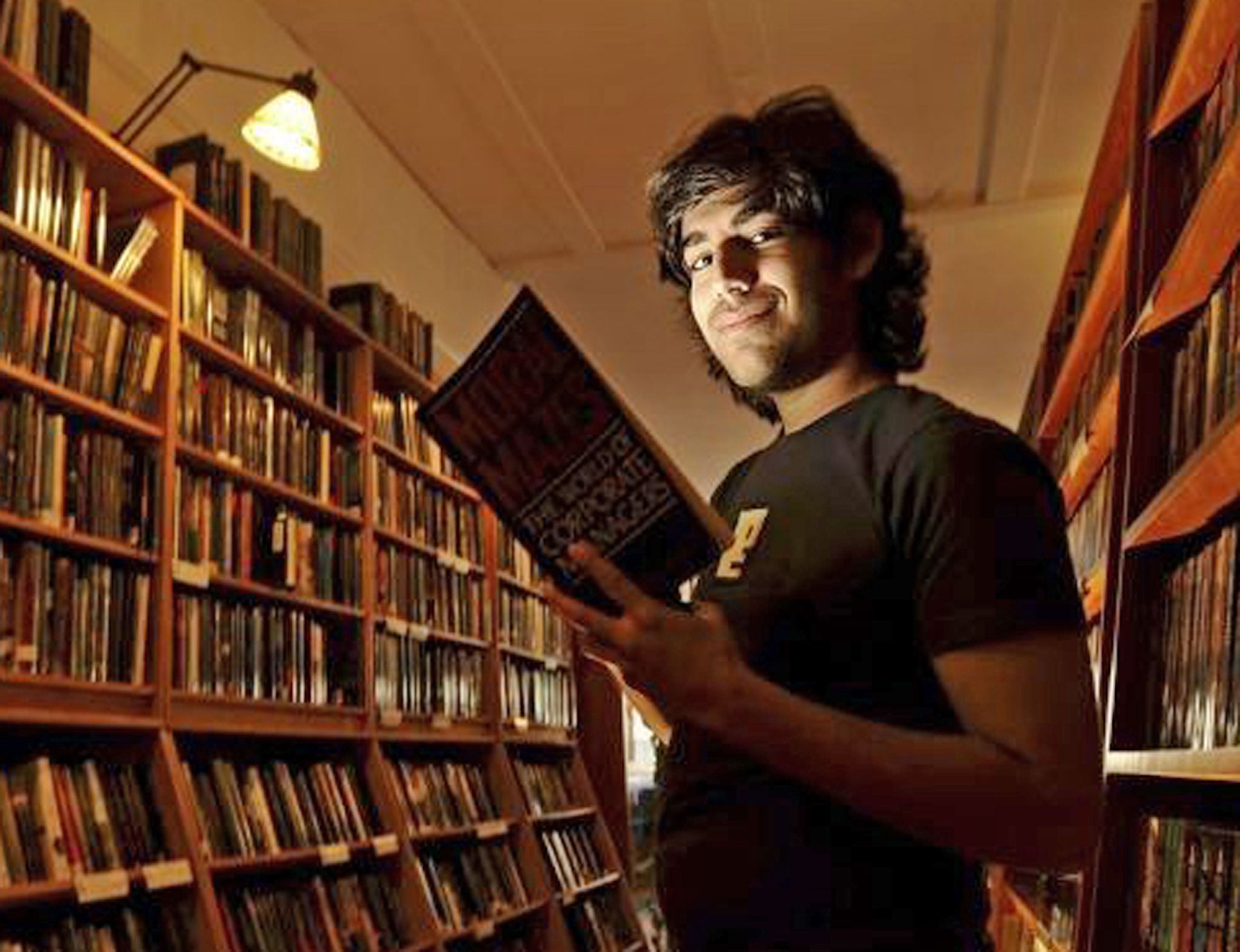

Your support makes all the difference.Two US representatives have introduced Aaron’s Law – a bill named after the late internet activist Aaron Swartz that proposes to amend American computer law that is currently “flawed and prone to prosecutorial abuse.”

In a joint statement published by Wired magazine, two of the politicians responsible for the bill – Zoe Lofgren and Ron Wyden; a Democrat representative and Senator from Califronia and Oregon respectively – have detailed the creation process behind the bill.

Lofgren and Wyden take aim at the current Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA), a set of “sweeping internet regulation that criminalizes many forms of common internet use” and that “allows breathtaking levels of prosecutorial discretion that invites serious abuse.”

“Vagueness is the core flaw of the CFAA. As written, the CFAA makes it a federal crime to access a computer without authorization or in a way that exceeds authorization. Confused by that? You’re not alone. Congress never clearly described what this really means.”

Current American law means people can be prosecuted for a range of technical infractions, including “lying about one’s age on Facebook or checking personal email on a work computer”. Other flaws in the CFAA include the fact that individuals can be punished multiple times for the same crime.

It was these flaws, and the actions of American prosecutors that contributed to the death of Aaron Swartz – an internet activist who was involved in the development of the RSS format and the Creative Commons licence.

Swartz was arrested in 2011 for computer hacking offences as defined under CFAA. Swartz had downloaded a large number of articles from JSTOR – a digital library for academic journals – and was subsequently facing up to a $1 million fine and a 35 year jail sentence. He committed suicide in January this year after which prosecutors dismissed the charges.

However, as Lofgren and Wyden make clear:

“Aaron’s Law is not just about Aaron Swartz, but rather about refocusing the law away from common computer and Internet activity and toward damaging hacks. It establishes a clear line that’s needed for the law to distinguish the difference between common online activities and harmful attacks.”

The main proposals contained within the bill include distinguishing violations of the CFAA from breaches of terms of service, employment agreements and the like; removing redundant portions of the CFAA that allow individuals to be charge multiple times for the same offense; and bringing “greater proportionality to CFAA” – ie, making finer distinctions between levels of offense.

For the bill to become law it will have to pass through Congress and then Senate. Lofgren and Wyden predict that correcting the CFAA will take “a significant amount of time” but that without action current law will become “an obstacle to the innovations of tomorrow”:

“Today, there’s an entire generation of digitally-native young people that have never known a world

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments