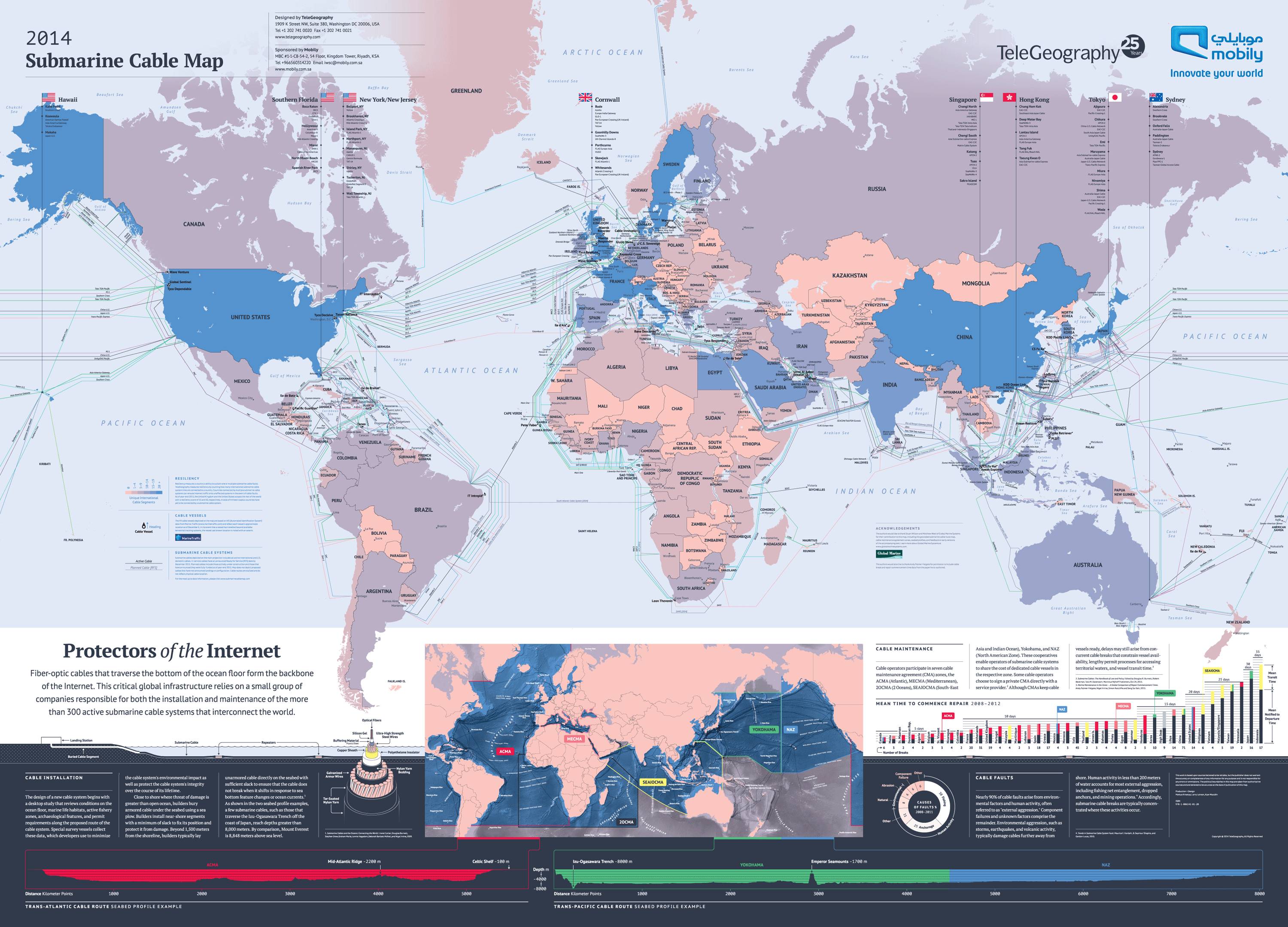

Mapping the tubes: The hidden world of undersea cables that make up the internet

Click through the gallery below to see details from the map or click the image above to see the full sized map

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When former US senator Ted Stevens described the internet in 2006 as a “series of tubes” he was mocked mercilessly, but as this map of the vast network of undersea cables that the internet runs through is anything to go by, he wasn’t too far off.

Created by telecoms data company TeleGeography, the map shows the paths, junctions and by-ways of the more than 300 fibre optic cables that exchange internet traffic across the globe.

Click through the gallery below to find out more about the undersea cables that make the internet a reality

Although we often think of the internet as something that is transmitted via satellites, in reality more than 99 per cent of international communications are delivered by undersea cables. Satellites are certainly good at broadcasting things but when it comes to exchanging data, cables are simply less fuss and much, much cheaper.

The foundations of the global map of cables you see above actually began with the invention of the telegraph in the 19th century. The first succesful transatlantic cable was laid in 1858 (it was nothing more than coppper wire insulated by gutta percha) and the first ever message sent over it was a congratulatory letter from Queen Victoria to US president James Buchanan on 16 August.

The message itself read “Europe and America are united by telegraphy. Glory to God in the highest; on earth, peace and good will toward men” and took around 17 hours to send. This oddly lengthy communication time was due mostly to the inefficiency of the copper cables used - but it was still a vast improvement compared to the ten days it would have taken to deliver the message by boat.

Paul Brodsky, a senior analyst with TeleGeography, says that by comparison, the typical transatlantic cable currently in use has a potential capacity of over 10 terabits per second - enough to transmit the entire English version of Wikipedia (minus images this is about 10GB) more than 7,500 over in a minute.

"The cables themselves are a bit of a Russian nesting doll," says Brodsky, "with the optical fibers themselves (each no wider than a human hair) embedded inside matrix of silicon gel, which is itself encased in a plastic casing, inside steel wires, inside a copper sheath, inside yet more armored cable, all wrapped in tar-soaked nylon yarn to protect against the undersea environment."

At the time of the first ever transatlantic message in 1858, the public was fully aware of the momentousness of the occasion and in New York they even celebrated with a 100-gun salute the morning after. Buchanan himself described the technological feat as “a triumph more glorious, because far more useful to mankind, than was ever won by conqueror on the field of battle.”

Even if Buchanan does sound as pompous as - well - as only a 19th century US president can, it does seem a shame that our understanding of international telecoms is now overshadowed by the grubby surveillance practices of various spy agencies - rather than the still-amazing reality of being able to talk to pretty much anyone in the world, at any time.

Click here to explore the original infographic from TeleGeography

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments