Malicious software hijacks your phone’s microphone and camera to record your PIN

New software could threaten the security of mobile banking

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A research paper from the University of Cambridge has outlined how PIN numbers used on smartphones can be recorded by hijacking the device’s camera and microphones.

The news is especially worrying as the rise of mobile banking means that PIN numbers entered into smartphones are often used to secure more than just the phone’s basic functionality.

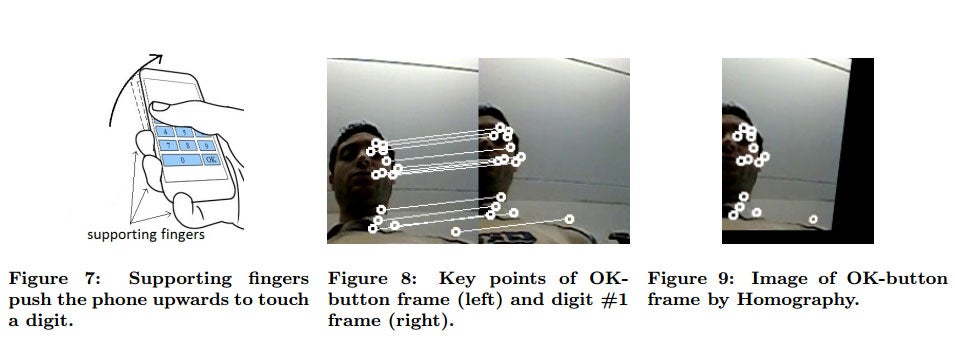

The researchers, Laurent Simon and Ross Anderson, used a custom piece of software called PIN Skimmer to grab the PIN numbers. This program hijacks phones’ microphones to detect when you tap the touchscreen and then syncs this with data from the camera to work out where on the screen you pressed.

For example, when right-handed individuals press a button in the top left hand corner of their phone’s screen they often tilt the phone towards their thumb with their supporting fingers. This changes position of the user’s face as recorded by the front-facing camera, giving the program a unique marker that corresponds with a number on screen.

The research was carried out on a pair of Android-powered smartphones, a Nexus S and Galaxy S3, and under test conditions PIN Skimmer was able to work out more than 50 per cent of four digit PIN numbers after five attempts and 60 per cent of eight digit numbers after ten attempts.

One step in the malware’s process even presents users with a game where they have to match pairs of icons that appear onscreen. The program can record data from the camera during the game and then use this as a reference guide, matching how the user appears in the camera to where they’ve touched the screen.

The researchers suggested methods of obstructing the malware, but noted that randomising the order in which numbers appear on an onscreen keypad would “cripple usability” whilst employing longer PIN number would affect “memorability and usability”.

More “drastic” solutions included getting rid of passwords altogether in favour of face recognition or fingerprint scanners, although neither of these methods are yet common.

"If you're developing payment apps [for mobiles], you'd better be aware that these risks exist," Professor Anderson told the BBC.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments