The Googles of tomorrow

From a book club taking on Amazon to the loans firm shaking up banking – Tim Walker meets the creators of the next digital superbrands

Zopa

Where do you want to go today? The future's bright. I'm lovin' it. These are the mantras with which our brands have mesmerised us. Microsoft and McDonald's aren't just consumer products – they're lifestyle choices. But all that is about to change. Or so says Robert Jones, director of brand consultancy Wolff Olins. He and his colleagues recently identified some of the next generation of brands. "The creation of myths around 20th-century brands is under threat," Jones explains. "We're too well-informed and too sceptical to believe in image. What brands have to do in the future is not create a big idea that people buy into, but be useful for people. The days of pure consumerism in the classic economic sense are over. Consumers are also creators, who interact with brands such as YouTube, and who make ethical rather than purely financial decisions when they're buying things. This is the age of the post-consumer. There's a French word for it: 'consommacteur'."

We consommacteurs are going to need a place to put the money we plan to plough into these new brands, and Zopa, one of those chosen by Wolff Olins, might just be that place. An alternative to traditional banking, Zopa became the first online lending and borrowing marketplace when it was launched in March 2005, financed by the same venture capitalists who were the original investors in eBay. "We took a practice that has been going on in communities around the world for centuries and created an online opportunity for it," says Giles Andrews, managing director of Zopa's UK operation, based in London. "We connect creditworthy borrowers with people who have some money that they would otherwise have used as investment funds or savings. By connecting the two parties directly, rather than via a bank, we can offer significant economic savings."

Zopa boasts around 185,000 members. While not all of them have made financial use of the platform yet, Zopa has nonetheless watched borrowing transactions of around £20m pass between customers since its launch. Without the unwieldy infrastructure of a traditional bank, the company can charge very low fees to its customers – about 1 per cent on average. The brand has launched in the US, and has plans to move into at least one major Asian market in 2008.

Often referred to as P2P lending, Zopa's structure is similar to that of a P2P, or peer-to-peer file-sharing system. "We diversify a lender's funds by dividing the full amount they want to lend into lots of mini-loans, and every loan a borrower receives is made up of contributions from lots of lenders," Andrews explains. "We've probably built a better-performing credit model than anyone else in the country because our bad debts are so minimal – less than 0.1 per cent."

Bookmooch

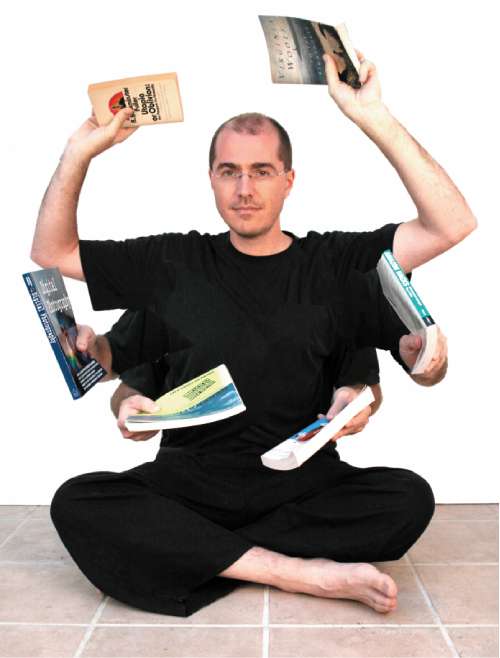

BookMooch is a simple but attractive concept: an online book exchange. John Buckman, the founder and CEO (right), had his eureka moment in Norwich. "I was in a community centre, with a bookshelf that had a big sign saying, 'Leave a book, take a book.' People were socialising and recommending books to each other. I thought: 'Could I recreate that feeling on the internet?'" Now he has his answer, with about 50,000 BookMooch users worldwide.

When you log on to BookMooch for the first time, you list the books you want to give away. For every 10 you list, you can ask for a book from someone else. Every time someone takes you up on the offer, and someone takes a book from you, you can ask for a book from someone else.

There are some 750,000 titles to choose from. If you send a book abroad you can claim three books in return. This sounds like bad news for publishers, but, says Buckman, "publishers are usually very excited by the idea of fans interacting directly with some sort of book site. They're happy to hear people are passionate about books. People correspond when they pass books along. When you read a book that you love, you want to give it to someone else so that they can experience it."

The personal touch is one of the keys to BookMooch's success: "BookMooch asks you to do something in the real world," says Buckman, "which makes it meaningful and emotional."

OpenMoko

If you think you've personalised your mobile phone, think again. "You can put rhinestones on it," says Steve Mosher, the vice-president of OpenMoko, "but you can't customise the operating system. If you wanted to turn your phone into something that controlled your TV, you couldn't." Until now, that is. OpenMoko has produced the first completely open-source handset. That means the software that makes everything work is developed by volunteers from across the world.

In 2007, OpenMoko sent its prototype handset – and the software source codes – to around 10,000 amateur developers. These outside contributors were asked either to submit improvements to the controlling software, or post new add-on applications online for other users to download to their handsets.

Mosher suggests the phone could be used to download medical records and organise prescriptions. It has found favour with archaeologists at the British practice Oxford Archaeology.

World66

Using Google to organise a trip abroad can be a test of endurance. Countless middleman websites provide unsatisfactory information on hotels, restaurants and flights. Which is where World66 comes in. A Wikipedia for travellers, World66 contains 80,000 articles on 20,000 destinations written and edited by fellow travellers. "All the brands we've chosen were designed to create a network effect, meaning the more people who get on that platform and use it, the better the whole thing works," explains Robert Jones of Wolff Olins (see "Zopa"). "They are brands people take part in rather than partaking of.

"World66 has that independent, Wikipedia spirit to it," Jones continues. "There are sites like TripAdvisor, which is a good place to go for the lowdown on a particular hotel, but it isn't really a travel guide. World66 goes a step beyond what Trip Advisor can do, because it's about all the things you might want to do while travelling rather than simply the organisational stuff like hotels, flights and restaurants."

Lulu

Lulu is a DIY publishing house. You write your book, upload it to the site, choose your cover, fonts and binding. Hey, presto! You're a published author. With no editors, Lulu has tiny overheads. Bob Young, Lulu's founder, says, "In traditional publishing, selling less than 20,000 copies isn't profitable. We thought there had to be a way to create a publishing opportunity for speciality authors who would only sell a few thousand copies a year."

Hence Lulu publishes anything technology textbooks to "the world's largest collection of bad poetry". Lulu has produced more than half a million titles, and there are more than 100 writers on the Lulu roster making a full-time living from the royalties. Lulu's bestseller, with 70,000 copies sold, is a how-to book for cancer patients facing chemotherapy called Putting the "Can" in Cancer.

Lulu's website has a recommendations system much like Amazon's. "On Lulu, you might find the only book ever published on the planet on a given subject," says Young, "because we make money, and the author makes money, on a single copy of a book."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments