Jaron Lanier: 'Web 2.0 is utterly pathetic'

He pioneered virtual reality and is a leading light in digital culture. So why does Jaron Lanier believe that the internet is killing creativity? Clint Witchalls meets him

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

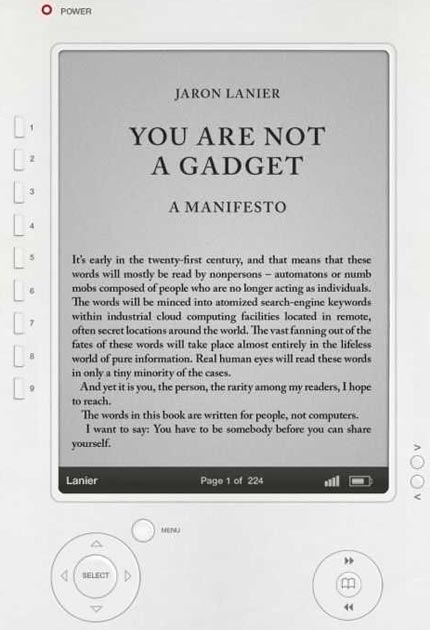

Your support makes all the difference.Jaron Lanier's book, You Are Not A Gadget: A Manifesto, has ruffled feathers in the US. The book takes a swipe at Web 2.0, accusing it of destroying individuality, destroying creativity and destroying middle-class professions. On the cover of the book are these portentous words:

"It's early in the twenty-first century, and that means that these words will mostly be read by nonpersons-automatons or numb mobs composed of people who are no longer acting as individuals. The words will be minced into atomised search-engine keywords within industrial cloud computing facilities located in remote, often secret locations around the world. The vast fanning out of the fates of these words will take place almost entirely in the lifeless world of pure information. Real human eyes will read these words in only a tiny minority of cases."

These are the sort of words you'd expect from a Luddite, not from the man who pioneered the development of virtual reality and continues to work at the bleeding edge of technology. But then Lanier is an oxymoron personified. He is a hippy, but he agrees with Rupert Murdoch that content should be paid for. He is one of the world's leading intellectuals – according to Prospect magazine's Top 100 Public Intellectuals Poll – yet he never managed to complete a university degree. He bashes big software firms, yet he provides consultancy services to them.

On the morning of my interview with Lanier, I enter the One Aldwych hotel lobby with some trepidation. The photograph on the dust jacket of his book shows a brooding man with a lion's mane of dreadlocks and a piercing stare. I'm quite unprepared for the animated, friendly person I meet. I'm instantly reminded of Professor Denzil Dexter, the hair-flicking Californian scientist from the Fast Show.

Lanier starts by ribbing me about journalists who automatically reach for Wikipedia as a first port of call. He wishes he could train journalists to be more sceptical.

I change the subject to Lanier's landmark birthday. "It's my 50th in May?" Lanier says. "Wow! I guess so."

"At least, that's what Wikipedia says," I add.

"In that case, I'm going to change my birthday."

In person, Lanier is a playful, upbeat person. It's hard to square this with the doom and gloom manifesto he has just published, even if Lanier insists that it is, overall, an optimistic book.

"Isn't Web 2.0 just a bit of harmless fun?" I ask.

Lanier looks bemused. He wants to know if I've read the book.

My question is only half in jest. Sometimes it's hard to get through the fog of Lanier's mystical denouncements of Web 2.0. About Wikipedia, he tells me: "It takes away from what it has given, so the usefulness and uselessness are interwoven." You're left to figure out the riddle for yourself.

I would agree that a lot of Web 2.0 is tedious piffle, but is it really a catalyst for the apocalypse?

"Web 2.0 ideas have a chirpy, cheerful rhetoric to them," says Lanier, "but I think they consistently express a profound pessimism about humans, human nature and the human future. Embedded in the Web 2.0 idea is a pessimism that people really could live off their brains. That's why it's OK for people to give their stuff away free because so few would have anything to offer that they'd have to have some other way to support themselves."

Lanier doesn't like the passivity of human nature that's implied by Web 2.0 – that people are mere receptacles for advertising. He is especially scornful of Facebook: "Lenin said, 'Property is theft.' [It was actually Pierre-Joseph Proudhon.] Facebook says, 'Privacy is theft,' because they're selling your lack of privacy to the advertisers who might show up one day."

There is an assumption that kids "get" Facebook and adults don't. But Lanier believes it's the opposite. Adults get it. Kids don't.

"If you're old enough to have a job and to have a life, you use Facebook exactly as advertised, you look up old friends," says Lanier. "I don't think you're doing anything wrong. If you're 17 you're caught up in reputation maintenance in a way that's really unhealthy. You have to constantly be on guard. It's like you're running for office. The degree to which you have to be on guard is so total and so clinically precise that you're not given any off-time to try another persona."

In order to create a persona, people need to be able to forget, but nothing is forgotten online. There is no space for young people to invent a new persona and try it out.

Lanier looks back fondly on the early days of the internet, when anything and everything seemed possible, not only in terms of the variety of technologies and architectures being explored, but also in terms of the variety of business models that were being discussed and tried out. It was a time of pioneers, mavericks and dodgy html. So where did all of the enthusiasm and idealism go?

Lanier writes: "Let's suppose that back in the 1980s I had said, 'In a quarter century, when the digital revolution has made great progress and computer chips are millions of times faster than they are now, humanity will finally win the prize of being able to write a new encyclopaedia and a new version of UNIX!' It would have sounded utterly pathetic."

Today, the web is a fairly bland place. It's all user-generated content – silly clips on YouTube, spiteful anonymous comments on blogs, endless photographs of people down the pub with their mates or up a mountain with an ironing board.

Despite the myth of the internet being a launch pad for aspiring musicians and journalists, it is actually killing music and killing newspapers. A couple of weeks ago, the International Federation of the Phonographic Industry (IFPI) warned that countries like Spain could become cultural deserts because of rampant online file-sharing. Sales by Spain's local artists have fallen by an estimated 65 per cent between 2004 and 2009.

"Musicians and journalists are the canaries in the coalmine," says Lanier, "but, eventually, as computers get more and more powerful, it will kill off all middle-class professions."

Speaking at an earnings call last week, Rupert Murdoch said that e-readers and tablet computers are "empty vessels" without creative content. Murdoch is going to try and get people to pay for News Corp content, but it's difficult to convince people to pay for something they've been getting free for years. Newsday, a New York-area newspaper, with the 11th-highest circulation in the US, began charging for content in October 2009. According to the New York Times, by 26 January 2010 Newsday had 35 subscribers.

The fact that no one wants to pay for digital content these days is evidenced by the fact that most of the internet's bandwidth is taken up by copies of pirated music, games, films, books and TV shows. Lanier suggests they should go.

"There'd be far less waste and far less carbon spewed by massive data-centres doing nothing but moving illegal files around," he says. "The internet is a huge device and it's being wasted."

And when something new is created on the web, it's often a banal "mashup" of old culture. Lanier likens the people who create these mashups to salvagers picking over a garbage dump. It is only in the old-world economy – the world of books, films and newspapers – that original content is being created. But Web 2.0 is steadily undermining the old-world economy in favour of one based on free content and selling social graphs to advertisers.

Lanier's big question is: will we be able to live off our brains in the future, or will we just have to give our creative works away for free? If we can't live off our brains then we need a form of socialism in order to survive. But Lanier's worst-case scenario is where only the elite get to live off their brains in which case society eventually splits into two species, as in HG Wells's The Time Machine, with its Morlocks and Eloi.

It's a grim vision.

"I've occasionally been wrong about certain things," says Lanier, "which is in a way more delightful than being right." I truly hope that the next decade brings Lanier lots of delight.

You are Not a Gadget: A Manifesto by Jaron Lanier is published by Allen Lane (£20). To order a copy for the special price of £18 (free P&P) call Independent Books Direct on 08430 600 030, or visit www.independentbooksdirect.co.uk

Heal the world wide web: Lanier's expert advice

* Don't post anonymously unless you really might be in danger.

* If you put effort into Wikipedia articles, put even more effort into using your personal voice and expression outside of the wiki to help attract people who don't yet realise that they are interested in the topics you contributed to.

* Create a website that expresses something about who you are that won't fit into the template available to you on a social networking site.

* Post a video once in a while that took you one hundred times more time to create than it takes to view.

* Write a blog post that took weeks of reflection before you heard the inner voice that needed to come out.

* If you are Twittering, innovate in order to find a way to describe your internal state instead of trivial external events, to avoid the creeping danger of believing that objectively described events define you, as they would define a machine.

Extract printed with permission

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments