Cyberclinic: The slot machine you carry in your pocket

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

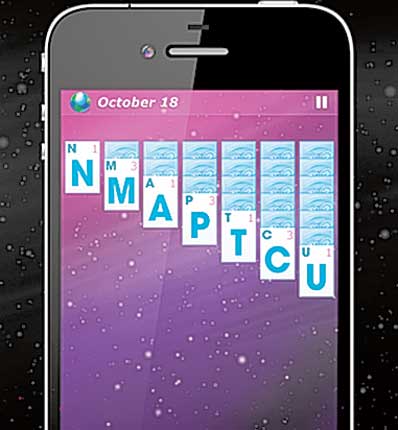

Your support makes all the difference.I'm sufficiently au fait with my own weaknesses to know that I ought to steer clear of computer games. I've had lapses that have verged on obsession over the years; Doom about a decade ago, World of Warcraft a couple of years ago – thanks to an assignment for this newspaper that got out of hand – and, more recently, Word Solitaire Aurora for the iPhone, which is like a never-ending episode of Countdown without the weak puns. But while playing these games I felt, however misguidedly, that I was undergoing some process of self-improvement. Doom enhanced my talent for blasting monsters into the ether.

Warcraft bonded me with fellow players in collective pursuit of some amulet or other. Word Solitaire transformed me into an anagram ninja. I don't regret spending time playing any of them. But a newish breed of social media game is being criticised within the gaming industry for requiring no skill and featuring tasks that are repetitive, tedious and shallow – the gaming equivalent of washing the dishes. Nevertheless, these games cleverly keep people playing and crucially, spending money.

Perhaps the best example is the Facebook-hosted game, Farmville. This game has inspired millions to spend far more time on Facebook than they would have done; around 10 per cent of the site's membership plays it. That's well over 50m people who have been persuaded – usually by their Facebook friends – that it would be a great idea to spend a lot of time cultivating imaginary crops. The makers of Farmville, Zynga, along with competitors such as Playfish, have perfected this gaming model that requires limited talent but maximum dedication, while also being supremely addictive. And while it costs people nothing to play initially, true devotees can enhance their experience by paying hard cash – often to speed up gameplay. (Impatience is just one of the human frailties that these games do their best to exploit.)

The model is spreading to phones. Smurfs' Village has been in the news for featuring heavily in several players' credit card bills come the end of the month; it joins games like Petville and Mafia Wars that appear in headlines such as: "Teenager spends family Christmas money on stuff that doesn't exist." These games are the 21st century slot machine: optimised to get us to shove as much money in as possible for a reward that will probably be fleeting and insubstantial. Obviously we're not all predisposed to slot-machine addiction, but the statistic that 90 per cent of revenue from these games tends to come from 10 per cent of its players is worrying, and one that gaming companies should probably be morally obliged to monitor.

Of course, we spend our money on all kinds of intangible junk of questionable value; who's to say that downloading a Michael McIntyre series from iTunes will give any greater pleasure to its recipient than if they bought a toolshed in Farmville? But some in the industry worry that if compelling games are replaced by purely addictive, money-generating timewasters, we'll become alienated from the medium as a whole. Especially when we realise that we've become little more than rats in a plastic box, repeatedly hitting a lever in return for a pellet.

A story surfaced at the weekend about an online spectacle vendor in New York who bullishly claims that he's found the perfect way of effectively promoting his business on the web: offer appalling customer service. When confronted, Watchdog-style, about his scamming of customers, he replied that he'd never had it so good. Because when people complain about his company online and link to his website, it ascends Google's page ranking for any searches for certain spectacle brands. And the more popular the website people use to complain, the greater the kudos Google bestows.

You see the same thing in the political blogosphere; irate left-wingers urge each other to follow links to a right-wing blog they find outrageous, ensuring said blog becomes even more prominent. Because until search engines are able to parse the English language properly and discern between a link of complaint and a link of praise, all links equal popularity. Paradoxically, we're in a situation where if we want to complain about a company on the internet, it's best not to mention its name. So beware this Christmas; if you want to buy something, don't blindly use a search engine – while they're brilliant pieces of engineering, they don't know everything.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments