Weak pound heaps food price inflation on poorest households

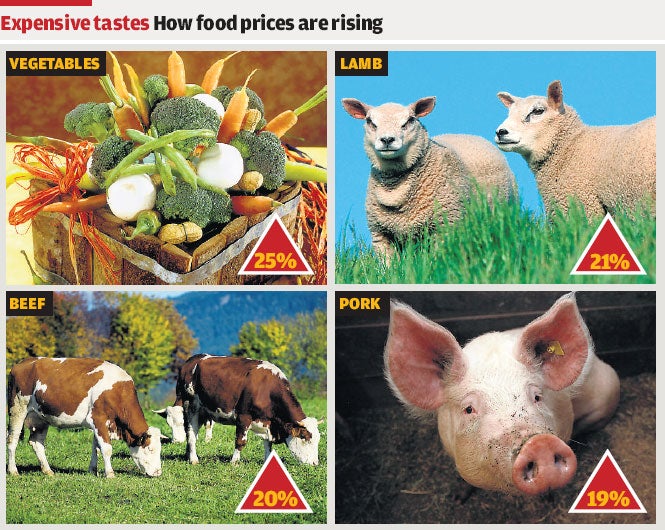

Soaring cost of imported goods sees grocery bills up by as much as a quarter

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The collapse of the pound on the foreign exchanges is keeping food price inflation at painful levels, with the heaviest impact falling on poorer households and pensioners.

The British Retail Consortium (BRC), which represents most major shop chains, reported yesterday a 9 per cent rise in the price of food in the shops in the year to March, against a fall in the prices of non-food items of 1.5 per cent. Prices were up 0.4 per cent month-on-month. Despite a general fall in inflation – the annual rise in the Retail Prices Index (RPI) hit zero last month – food prices remain stubbornly high, and rising.

Imports of fresh vegetables from eurozone nations such as Spain have become especially dear – up by around one quarter. Other foods that have seen double-digit price rises since 2008 include lamb (21.3 per cent), beef (20.6 per cent), pork (19.7 per cent), cereals (16.1 per cent) and milk (11.5 per cent). British lamb is becoming an expensive delicacy, up 26.7 per cent, the largest jump of any food item in the RPI.

Because so many food prices are determined globally, home produce prices have also been pushed higher by the fall in the pound, as the price of otherwise comparatively cheap UK produce has been bid up by foreign buyers.

The BRC said: "Although around 60 per cent of food consumed in the UK is sourced domestically, the grocery industry is a global market place and hence exchange rate fluctuations affect the price of produce and production. The farm gate price of UK-produced foodstuffs has increased markedly as sterling has depreciated, to maintain parity in the price of similar goods sourced in other currencies in the global market place."

Those households where food prices and utility bills (which are rising even faster) represent a big proportion of the budget are seeing little benefit from the much-heralded onset of deflation. The Institute for Fiscal Studies recently found that the richest fifth of households had an average inflation rate of minus 1 per cent; the poorest fifth had an average inflation rate of 5.3 per cent. The least-well off pensioner households, usually with no mortgage and no benefit from the cut in Bank rate, are still coping with inflation at 6.9 per cent.

World food prices, while some way off their peaks of 2007 and 2008, remain very high by recent historical standards, about double where they were in 2003, according to the UN's Food and Agriculture Organisation.

The same sort of pressures that pushed up food prices during the boom are largely still there: rising populations; changes in diet in fast-emerging societies such as China (where resource-intensive meat and poultry is replacing efficient rice); pressure on land use from biofuels and human settlement and growing shortages of water. Climate change is also liable to adversely affect food production. The World Bank estimates that higher food prices have increased the number of undernourished people to close to one billion, out of a global population nearing seven billion.

A report prepared for the forthcoming get-together of G8 agriculture ministers in Italy – the first "food summit" of its kind – hints at the possibility of food wars in the future, or, as the report phrases it, "serious consequences not merely on business relations but equally on social and international relations, which in turn will impact directly on the security and stability of world politics".

The long-term problem of meeting a doubling of food demand by 2050 from a world population of nine billion is moving up the international political agenda. Some nations, such as Korea and Taiwan, have been buying huge swaths of arable land in the developing world as a way of assuring food security. Around 73 million people now depend on the UN's World Food Programme for their sustenance.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments