Veuve Clicquot Rich: How sweeter, softer champagnes are attracting younger drinkers

Samuel Muston raises his glass

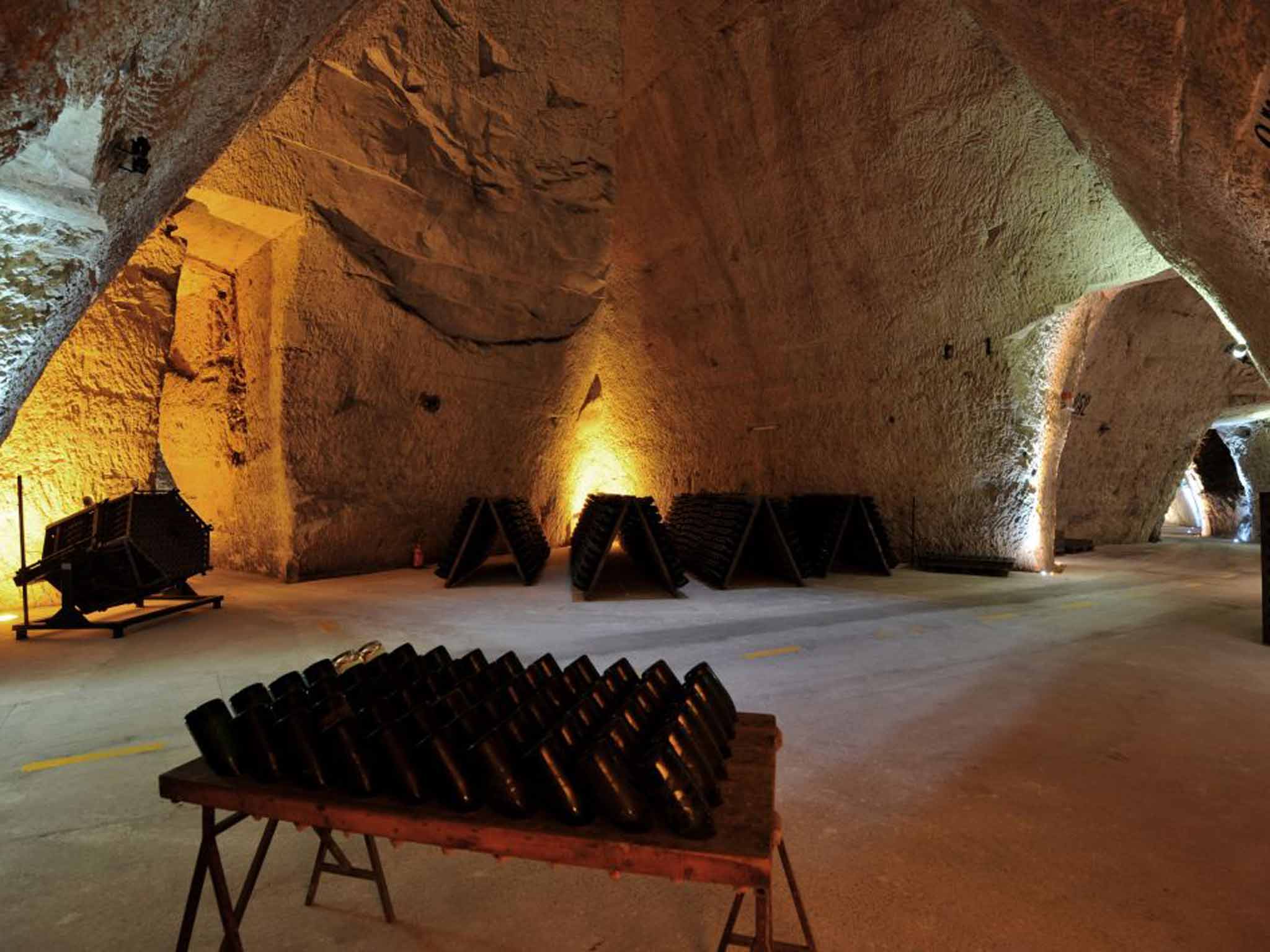

When you are 20m underground in a chalk quarry dug out by the Romans, it's hard to imagine you're going to come face to face with the future of anything. Quite the reverse, in fact – it seems like the sort of place where futures end. And yet here I am, in Veuve Clicquot's limestone cellars, staring at a bottle that may represent the future of this 243-year-old house.

The green glass is at this point unmarked by labels. It is hermetically sealed with the sort of silver metal top you see on stubby bottles of lager, a necessary step before the cork goes in after the sediment goes out. It is indistinguishable from the tens of thousands of other bottles that fill the 24km of caves which reach out like tendrils underneath the champagne town of Reims.

Yet, when its three years of maturation are over in the sloping pupitres [racks] created by the house's founder, Madam Clicquot, and long after a 60g dosage of sugar has been added, the bottle will be taken away and coated in a reflective, disco-ball silver coating.

Now, anyone familiar with how champagne is made – and marketed – will know that two things are unusual about this. First of all, the amount of sugar that is added in the dosage – your common-or-garden champagne has around 9g; the Richer Veuve demi-sec has 25g. Secondly, and perhaps the more pressing question, when did Veuve start going all disco? Since June, to be exact, when its Veuve Clicquot Rich was released. The company's president, Jean-Marc Gallot, said at the time, “tradition is good in life, but in this challenging world, we have to push the boundaries”.

And push the boundaries they certainly have. What is really surprising about Rich is that it is made to be mixed with another ingredient, and ice, to make a cocktail – or, as a Veuve winemaker says firmly when I use the c-word, “Rich is for mixology.” The presentation, too, is unusual. When champagne is sold to us it is usually on the basis of the house's heritage, its obsession with quality, and all accompanied by a cocktail umbrella of holier-than-thou reverence for the fizzing golden stuff. Essentially, it's marketed as if buying a bottle will suddenly transpose you into an Evelyn Waugh novel.

The 10-second YouTube advert for Rich, on the other hand, features a pumping Noughties nu-rave tune over images of 20- to 30-year-olds cavorting, variously, in a Parisian park, a smart club (you can tell it is smart – people are in suits), on a New York rooftop, and by a swimming pool, which may or may not have some kinship to David Hockney's pool. Veuve has also teamed up with evergreen fashion photographer Nick Knight to curate a Hallowe'en event and exhibition called The Widow Series. You don't need to be Roland Barthes to unpick the underlying message here: this a new drink, for the young, the moneyed (it retails at £59.99) and the fashionable (it's currently available exclusively at Selfridges).

Veuve is the third major champagne house to plough this furrow. Two years ago at Wimbledon, Lanson released a white-label champagne similarly made to be served with fruit, though not over ice. Moët entered the fray with a version, which is served on its own in a balloon glass filled with ice, and was launched at a roof party at a modish central London hotel in June. Called Moët Ice, it is now a familiar sight in upscale nightclubs and beach bars.

All this cuts so far against the grain that it raises the question why. And why now? The answer, says Edwin Dublin, a champagne specialist at Berry Bros and Rudd, is what one might term the prosecco effect. “They aren't trying to convert existing [brut champagne] customers, rather bring more people into the category. It is a new demographic – mainly younger, as they recognise this age group generally prefers sweeter and softer styles of wine, such as New World wines and prosecco. As Michelle Cherutti-Kowal of the Wine and Spirit Education Trust points out, ”The trend among champagne-lovers is for less sugar – zero dosage and brut nature“.

While the target market for the drink is new, this style of sweet wine actually harks back to something much earlier. As we make our way out of the cellar to go to a tasting, we pass a bottle that seems to have been imprisoned – the undulating green glass is held behind bars in a secure section of the cellars. This 170-year-old champagne – still, apparently, drinkable – was part of a haul recovered from a wreck found off Finland's Aland Islands. It was one of 40 bottles of Veuve bound for the tsar's court. The sugar dosage in this bottle is a dentist-scaring 150g, two and a half times that found in Rich. As our guide says, with some understatement, “the Russians had a sweet tooth”.

Sweet champagne, in fact, dominated for centuries. Drier brut-style champagne was created initially only for the English market, though it has since attained a certain, throat-ripping hegemony. When you taste Rich, you are not immediately hit by the tsunami of sweetness you might expect. That probably shouldn't be much of a surprise given that the wine, a blend of pinot noir (45 per cent), meunier (40 per cent) and chardonnay (15 per cent) is fine-tuned by a 12-man blind-tasting committee and the Chef de Caves Dominique Demarville. What it tastes of is the things it is mixed with – Veuves suggest serving it with grapefruit or cucumber or a cold silver-leaf tea. It is this attribute that makes it popular with bartenders. Champagne has long been used in cocktails, of course – Mrs Beeton's 1861 Guide to Household Management had a recipe for one involving seven ingredients and a silver chalice – but champagne was generally seen as showy and not particularly agreeable in a cocktail.

“The sugar in Rich balances a cocktail,” says Tawa Tanye, bar manager at Café Royal's club. “When you add another ingredient – I use green tea – it acts as an enricher, bringing that flavour out.” Cherutti-Kowal agrees. “The higher sugar levels mean the mixologist does not need to add sugar. Sugar does not integrate well, so a sweeter base works better. It also re-introduces champagne's versatility into the mindset”.

The real question is, will it change the world of champagne? Probably not. Purists will always want their wine unmolested by fruit and ice and brut champagne is the style du jour, and probably the day after du jour, too. But what Veuve Clicquot Rich and the other styles like it do is open up the world of champagne to a new audience. What its bottle and just about everything else about it is saying is: you can enjoy me on a beach, at 2am in a nightclub or anywhere you choose – you don't need to worry about posing as a connoisseur, you just need to have a nice time drinking me.

In the world of champagne, where pretentiousness often comes by the case, it is a welcome message.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies