Think more, eat less: the dangers of emotional snacking

Snacking that is triggered by anger, grief or frustration is an eating disorder in itself, according to Dr Jane McCartney, an expert in emotional eating. She tells Lena Corner how she learnt to stop feeding her feelings

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A couple of summers ago, psychologist Dr Jane McCartney booked herself and her family on an all-inclusive holiday. While she was there, she seized all the endless eating opportunities with both hands, and by the time she arrived home, she had ballooned.

"I came back and thought, 'Why have I done this?'" she says. "I was so used to listening to other people in my practice that I was ignoring what was going on with myself. So I sat down and thought, 'What is really going on here?'"

She started writing down what she was eating and when, and realised that there were other things at play. She was having a pretty bad time generally in her life. She had recently been involved in a car crash and her grandma had just died. McCartney concluded there must be a connection – grief and despondency were causing her to eat unnecessarily.

For the best part of a decade, McCartney has treated people for anxiety, addiction and relationship difficulties. It became apparent to her that weight issues and problematic relationships with food were very often associated with these things, and often a symptom of them. These people were turning to food, not because they were hungry but because a specific emotional chain of events caused them to reach for it whenever stress or anxiety set in. She looked around for something to read on emotional eating and besides a couple of American books, there was nothing. So she set about writing her own, entitled Stop Overeating.

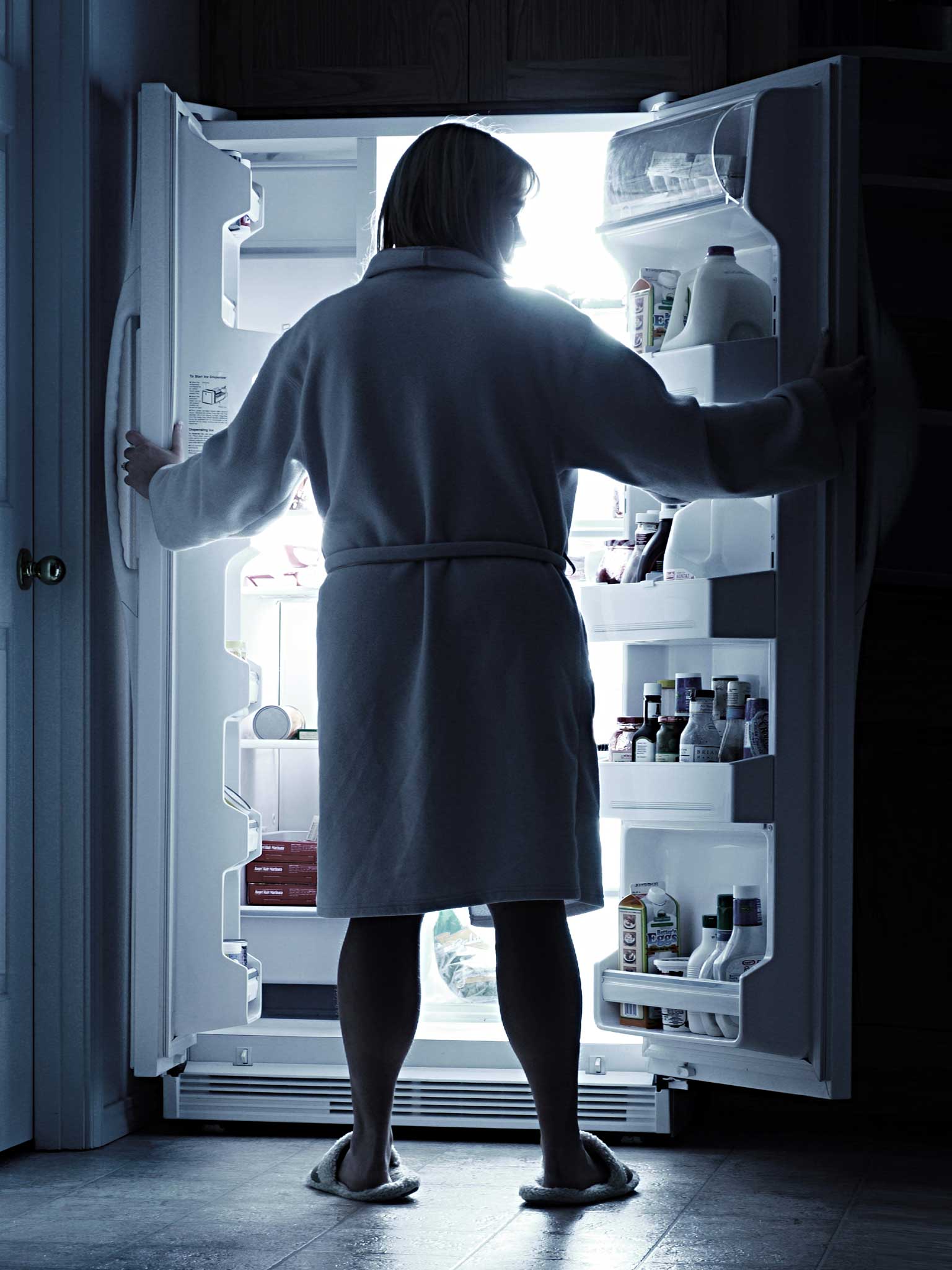

"People would come to me saying, 'I've got depression', or whatever, and pretty soon it would emerge that one of the most significant things that was linked to their mood was their eating habits," she says. "I have been an over-eater myself, so I know where they are coming from. There's been many a time I have found myself standing in front of the fridge, thinking, 'What am I doing here? I'm not even hungry'. When your eating habits are tied to your emotions in this way, it can become all-consuming, like a classic eating disorder."

And we've all been there. We've all reached for that chocolate bar when we're not remotely peckish, or demolished a packet of biscuits without knowing why. We may casually brush it off as comfort eating, but McCartney's book recommends taking a deeper look. She suggests exploring what may be causing these episodes of over-eating, or emotional eating, by asking questions about what influences these urges. And to do this, she says, we need to ask what's going on in the background – both short-term and long-term – with our relationships, our working lives, our self-esteem; everything.

"These are the things we look at in the first instance," she says. "We need to be aware of what's going on for that person. All of these things send emotional messages and then we need to explore that message – where it comes from, who is influenced by it and who maintains it. If it's constantly problematic, you have to do something about it. Unless you are looking at the why you eat, not so much the what you eat, then you are going to go round in circles."

McCartney accepts that our relationship with food is formed from a very early age. Her father was a typical war child and insisted that everything was finished on plates and nothing was eaten between meals. "There was no sense of pleasure from food. It was, 'This is yours and if you don't eat it you'll go without'," she says. "The moment I got my first Saturday job in a hairdresser, all my money used to go on crisps and milkshakes, because it was suddenly my little bit of freedom. My relationship with food wasn't good from the start. When it is imbued from so early on, it's difficult to change it, but you can learn to manage it."

"One of the things that I encourage people to do is to work out long you are going before you have something in your mouth. I don't mean just food. I mean drinks such as tea and coffee, too. It's amazing how many people will actually realise often it's barely 40 minutes. We've got into the habit of permanent grazing. And once you are aware of that, you can challenge it."

Many of us also need to break the cycle of self-blame, and not give ourselves too hard a time if we over-indulge. "Instead of going down the self-sabotage route, where you think you've blown it – so you might as well blow it for the rest of the day, which will lead to self-loathing – just forgive yourself and pick up where you left off."

Passing on good habits to children is really important, too, so that they don't grow up with the same issues. She advises not to impose blanket bans on anything; allow burgers and chips once in a while and just encourage moderation. Also, she says parents should never use food as punishment or praise.

"If you start saying, 'If you don't do your homework you won't get pudding', it will build up a skewed relationship with food," she says. "Food can become a weapon of control, which is classic in people who have eating disorders." McCartney is now down to a regular size 12. No longer does she feel the need to hide the size 16 label on her cardigan when she hangs it on the back of her chair at work. And she's hovered roughly around that same weight for a while now. It's clearly worked for her and she's never had to starve herself or follow a particularly restrictive menu. In many ways, it's a radically new take on dieting – after all, if we didn't overeat, we wouldn't have to diet in the first place.

"Diets may work for a few people, but dieting alone – restricting what you eat as a standalone thing – is always going to be difficult, because your emotions are heightened and you are grumpier because you are hungry," she says. "And those are exactly the danger times."

At the back of the book, McCartney provides a 28-day eating plan to get people started. It's just simple, affordable recipes she cooked up with her family in her kitchen at home.

And it's definitely not a diet.

"We can't change the past," she concludes. "I don't have magic wand or a time machine, but a little bit of acknowledgment and awareness of the issues that trigger you to eat too much goes a long, long way. It can stop you from dwelling on things and give you the tools you need to move on."

'Stop Overeating: The 28 Day Plan To Stop Emotional Eating' is published by Vermilion this Thursday, £10.99

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments