Samuel Muston: The Pauper's Cookbook - delicious revival of Jack Monroe of the 1970s

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It was the gravy that did it. Dribbling lazily down the pot on the front cover, it looked so slovenly. So unlike the other cookbooks on my parents shelves. Elizabeth David and the other heavyweights of the kitchen bookcase wouldn't have stood for that gravy.

By the time I came across it in the 1990s, my parents' copy of Jocasta Innes's The Pauper's Cookbook was in the evening of its days – stained, torn and singed at the edges – but it drew me in like a bowl of cake mix. It was perfect for a child, assuming little prior knowledge and not aiming for an ethereal, Frenchified vision of perfection. It was a good friend to my family, that book.

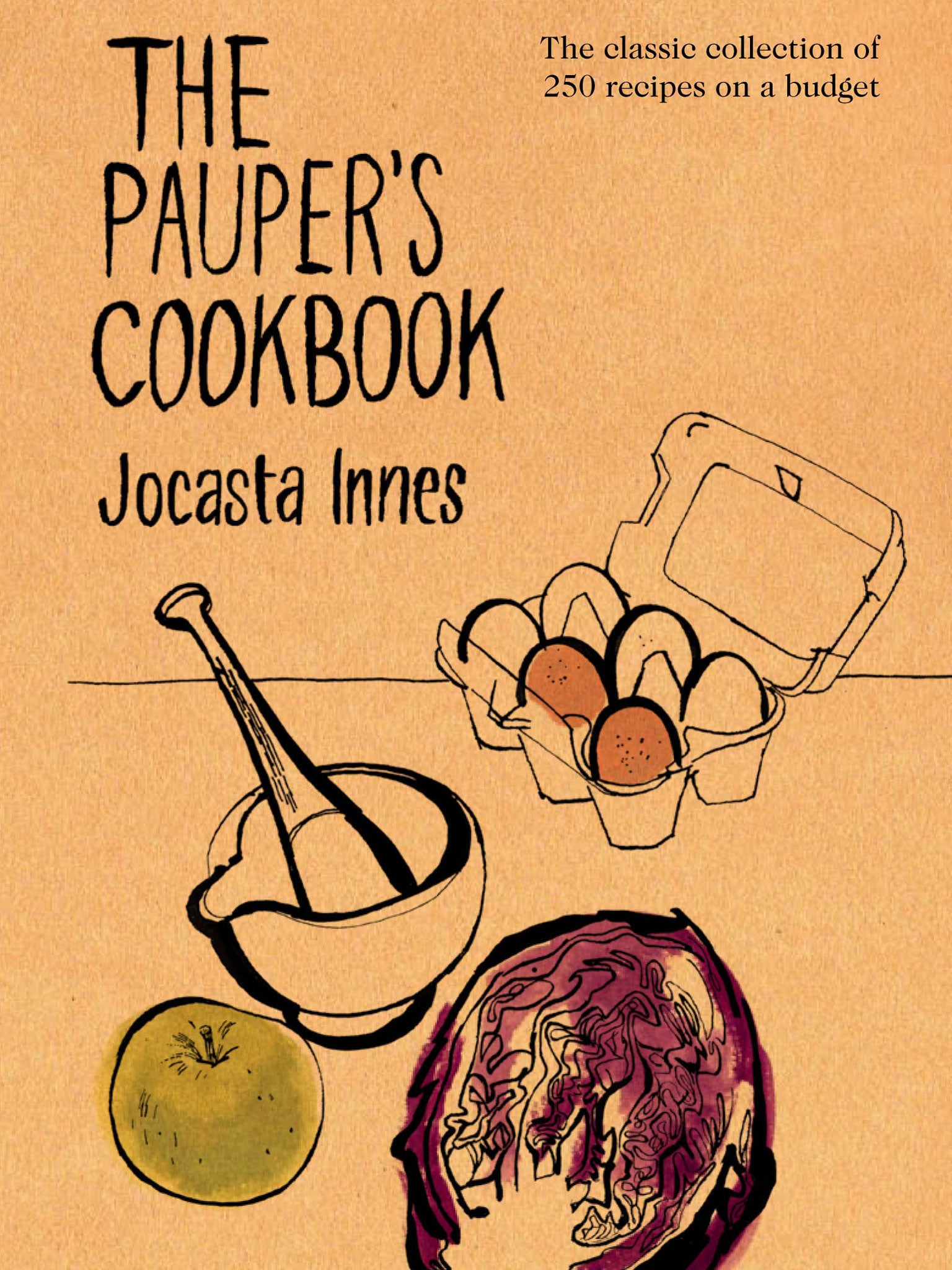

I must admit, though, I had quite forgotten it: it had long ago slipped into that pit in my brain where my knowledge of GCSE chemistry and pure maths lives. This week, though, Frances Lincoln publishes an updated version of Innes's 1971 classic (below). The cover may have changed, though there is still a touch of the flaired trouser about it, but the contents are largely untouched. And that's a boon.

It was, in its day, quietly revolutionary. The book's conceit was both simple and attractive: it aimed to help indigent cooks produce "good home food at Joe's Café prices". The 150 recipes were spread across chapters with uncompromising titles, such as "Padding", "Fast Work", "Fancy Work", "Dieting on the Cheap" (this last one has been removed from the new version). It showed people how to take creative possession of modest circumstances.

The recipes themselves were diffuse. A "meal in a potato" – which requires a large spud, butter, cheese, nutmeg and egg – rubbed up against the rather grander "stuffed mussels". There were outliers like the "British Rail Salad", which takes in quail eggs, black pudding, garlic and leaves, and familiars like bread and butter pudding. What drew them together was the fact that you could knock up any of these dishes on a budget of two and sixpence per person per meal (about 60p today) which, incidentally, was what Innes was living off while writing it, having left her husband, the producer Richard Goodwin, for a life of bohemian penury in Swanage with the novelist Joe Potts. She was, in some senses, the Jack Monroe of her day.

While some of the recipes in the book seem a little dated today, others are as fresh as ever. But half the fun of the 280-page book is to luxuriate in Innes's style. Her style of writing is not unlike the previously mentioned Elizabeth David and, like her, she pulls no punches. But I always used to think of her as a counterweight to the blessed David, whose recipes can be so know-it-all and who certainly never lived impecuniously in Swanage.Writers like David are so skilled at evoking flavours and places, which are so far away – it makes their work timeless – whereas Innes and, indeed, Jack Monroe write practically for the here and now. David might be a culinary god but Innes has her place too.

Perhaps my parents thought as much, too, for I remember Elizabeth David's books lived on the top shelf in our kitchen – like some holy text. The Pauper's Cookbook, however, lived two storeys down. They are books of different status, certainly, but 43 years after it was first published, The Pauper's Cookbook should still have a place in every modern kitchen.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments