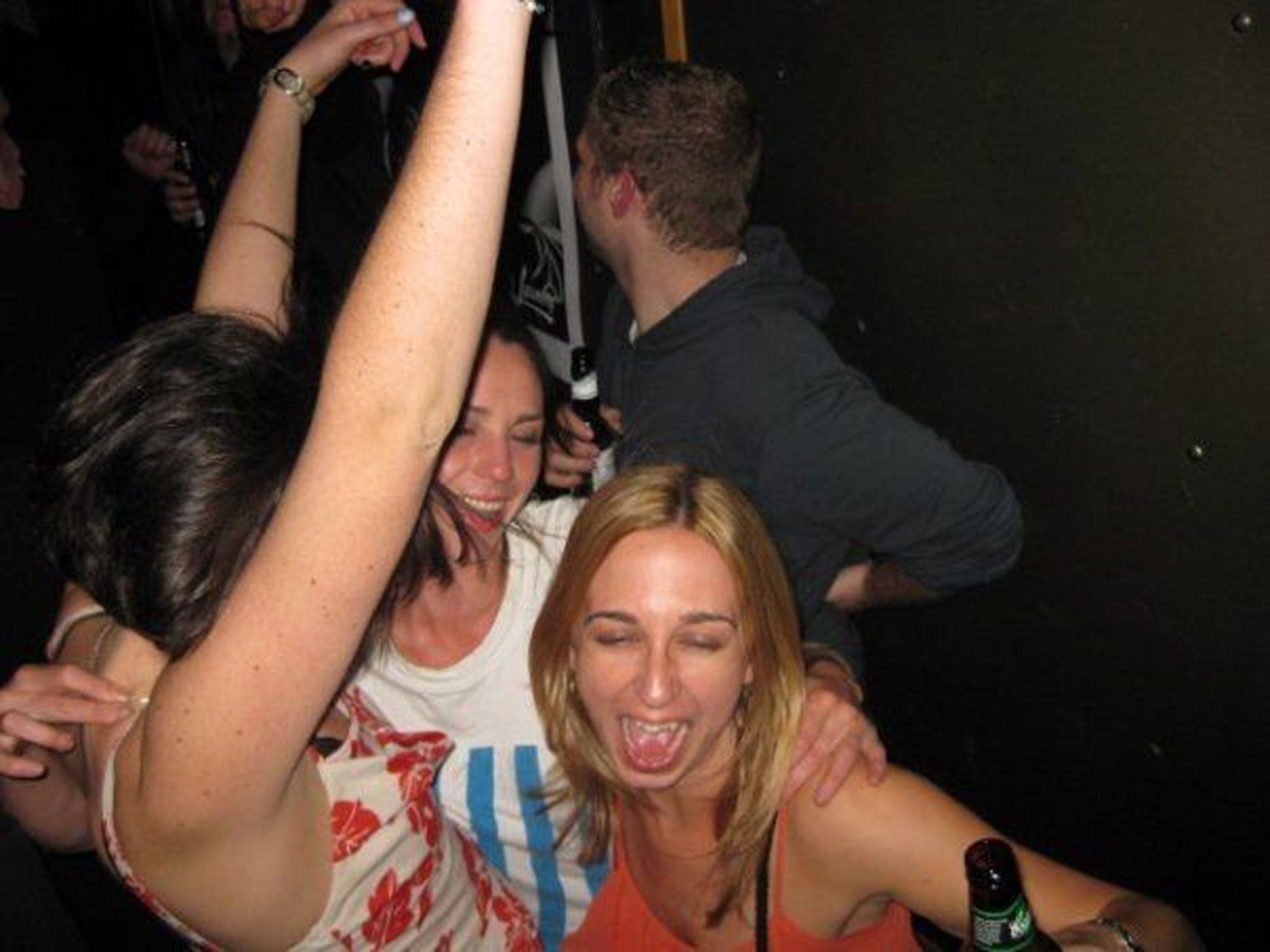

Could you manage a year without booze? This woman's New Year hangover made her teetotal

How does a binge-drinking health reporter celebrate New Year? With a hangover – then a year of sobriety

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.If you vow never to drink again after waking up on New Year's Day morning, chances are you won't be alone. Whether deciding to have a break from alcohol is a new year’s resolution, a dose of sponsored sobriety courtesy of Alcohol Concern’s Dry January or Cancer Research’s Dryalthlon or simply a case of feeling sick at the thought of imbibing booze after weeks of festive partying, January is the time when taking a break from the bottle doesn’t just seem sensible, it’s almost mandatory.

The idea of paying penance at the start of the year is one that Jill Stark, a Scottish-born and Australia-based health writer, has made her name with in her book High Sobriety: My Year Without Booze, a best-selling memoir that explores her relationship with alcohol, as well as its place in British and Australian life. What started as a challenge to spend three months without a drink turned into a year-long period of abstinence that saw her re-evaluate who she was and why alcohol had become such a large part of life for her and her peers.

“Giving up alcohol changed everything really, in ways I hadn’t expected,” she explains over the phone from Australia. “I thought it would be a case of getting a bit healthier but I actually found out a lot about myself along the way. I realised that some of my friends weren’t really friends, they were just drinking buddies. Some people stopped inviting me to parties and the pub and stuff I guess because they thought I wouldn’t be much fun! Because I’d always been that party girl, it forced me to look at my identity. Who was I without a glass in my hand all the time? It actually also taught me to be a lot more confident, which is surprising, because at first it was very confronting to be someone who always socialised with alcohol to suddenly not have that social lubricant or that social crutch.”

It wasn’t just socialising that proved to be a testing ground for her confidence. Her account is a brutally honest one that lays bare her drinking habits, which are at odds with her professional reputation as a senior health reporter.

“I was essentially outing myself as the binge-drinking health reporter. I was very well respected in the health, drug and alcohol sector as someone who’d written about the scourge of binge drinking, someone who’d held the alcohol industry to account and here I was saying that I was part of the problem. I wondered if I’d lose the respect of some of my professional contacts.”

Her honesty, though, led to her winning a prestigious drug and alcohol media award for the second time. But it’s also meant that she is always asked about her drinking now. “Whenever anyone asks me that, I always want to say “actually, I’m drunk right now!” I said it live on television one night…” Stark says, laughing. “It is quite a challenge as I’ve become the poster girl for sobriety, which certainly wasn’t my intention. It’s not a book demonising alcohol, it’s my own personal journey with it and about getting my balance right.”

In this extract from her book, Stark describes the New Year’s Day hangover that finally broke her – and made her find her inner teetotaller.

***

“The roar in my skull sounds like waves battering a shore. My head, planted facedown in a sticky pillow, feels as heavy as a waterlogged sandbag. My body is a dance floor for pain. Welcome to 2011, Starkers: a new year, a new start; same old stinking hangover.

Last night was huge. Dawn had broken by the time I staggered home. I remember cursing the light and the chirpy birds. It was, like so many before it, a party that had got away from me. It had been a ridiculously hot Melbourne New Year’s Eve: dry and oppressive, with a blasting northerly wind. I felt as if I was trapped inside a fan-forced oven. As I sipped my first drink – a stubby of beer – with friends in their backyard paddling pool, the mercury crept past 40 degrees. It was 6pm.

As the night wore on, there was champagne with strawberries, more beer, more champagne, and then even more beer. There were sparklers, dancing, and high-pitched phone calls to Scotland, where it was still the last day of the decade before. I vaguely remember a fiercely contested drawing competition with crayons, and, for reasons I can’t fathom, sitting atop a stepladder with a miner’s lamp strapped to my head.

Later, at another friend’s house, we had White Russians in tumblers, and tequila in martini glasses. I remember one of my friends vomiting in the kitchen sink, and the group blithely singing over it as if this was neither noteworthy nor unusual. I remember thinking, when’s this going to stop? Then having another beer for the road.

I roll over on to my side, releasing a deathbed groan. The alarm clock comes into view, its illuminated digits stabbing my eyes. It’s 2pm. Another groan; this one seems to come from my bones. My guts churn as a tribe of African drummers pounds out a rhythm in my brain, and I pay a grudging respect to a hangover that, having been almost a month in the making, has arrived with some fanfare.

Being conscious hurts. I gag as I think of all the booze I put away in December – one long party interspersed with stolen moments of sleep and tortured days at work. But covering alcohol is my job. During the week I write about Australia’s booze-soaked culture; at the weekends I write myself off. For five years I’ve documented the nation’s escalating toll of alcohol abuse as a health reporter for The Age and The Sunday Age, so I know, more than most, the consequences of risky drinking. I’ve even won awards for my “Alcohol Timebomb” series, which highlighted the perilous state of our nation’s drinking habits. But it hasn’t deterred me. I’m always first on the dancefloor and last to leave the party. At 2010’s staff Christmas bash, I won the inaugural Jill Stark Drinking Award. Bestowed upon me for recording the least amount of hours between partying and turning up to work, I celebrated the honour with a beer. When colleagues remarked on the irony of my role as health reporter, I told them it was “gonzo journalism – just immersing myself in the story”. Then I danced into the next morning, breaking my own record by stumbling into work after four hours’ sleep, my title safe for another year.

I stuck the beer-stained certificate on my fridge, ostensibly to show off to friends, but really to serve as a reminder that this was, or should have been, a line in the sand. Yet the festive season leaves little time for self-reflection. There’s always another party.

I powered on, and on, and on, until the hangover of all hangovers brought me here.

An ungodly noise reverberates around the room. It’s impossibly loud. I wrestle with the doona, unearthing my mobile from a pile of clothes. It’s my friend and colleague Nat. I can’t talk to her. The inside of my head is a graveyard for brain cells. Those that survived last night are clinging to life, resting on the backs of their fallen comrades, too weak to help me form words. I turn the phone to silent, waiting for the message bank alert to vibrate.

“Hi darl’, happy new year! “Nat trills in her singsong voice. “So sorry to bother you on your day off, but I really need your help. Brendan Fevola’s [an Australian footballer] been arrested for being drunk, and I have to do the story. I need to find some alcohol experts to talk about whether he should be in rehab, is his career over, where to next, that sort of thing. Was hoping you’d be able to put me on to some of your contacts. Anyway, hope you had a good night. If you can call me back, that would be great.” It’s an hour before I recover the motor skills to send Nat the contacts. Scrolling through my phone, I find the mobile numbers of Australia’s leading authorities on alcohol abuse. The chief executive of the Australian Drug Foundation, the chairman of the National Health and Medical Research Council’s committee on alcohol, the head of the Prime Minister’s National Preventative Health Taskforce: these are men who trust and respect me, men who will draw on their decades of expertise to speak eloquently on the best road to rehabilitation for a troubled young footballer who has had one big night too many.

But what about me? As I lie here, enveloped by a sense of shame and the stench of stale pale ale, the only thing louder than the thumping pain in my head is a noise I have tried to ignore for months: the tick, tick, tick of my own alcohol timebomb. I’ve been a binge drinker since I was a teenager. Growing up in Scotland, a place where whisky outsells milk, and teetotalism is a crime punishable by death, devotion to drinking is as much a part of my national identity as tartan, bagpipes, and Arctic weather conditions.

I had my first drink at 13 – a can of lager that my best friend Fiona and I stole from my parents’ drinks cabinet. We laced it with sugar in a failed attempt to make it taste less revolting, and drank it through a straw because we’d heard this would get us pissed faster. It would take many years before I warmed to the taste of alcohol, but I immediately fell in love with being drunk. It felt freeing, exhilarating, and endlessly fun and hilarious. It opened up a world where life’s sharp corners were blunted, and worries melted like chocolate on a sunny dashboard. I couldn’t believe it was legal.

Since then, I’ve rarely questioned my big weekends. Getting drunk is the social norm, and as much a part of life as eating and sleeping. Moving to Australia in my mid-twenties, I was delighted to discover that my adopted country had a similar affection for alcohol. Many times I’ve vowed “never again”, as what has begun as a few quiet drinks invariably turns into a lost weekend. Then, when the hangover fades to a dull memory, I do it again. Alcohol accompanies almost every aspect of my social life: parties, gigs, dinners, birthdays, holidays, book club, work functions. Even my dance class is held in a pub. Drinking socially has become an act as automatic as breathing.

But something has changed in recent months. My 35th birthday looms, I have a grown-up job and a ridiculous mortgage, and my knees now make a cracking noise every time I stand up. I can no longer afford to drink as though I’m a teenager. The hangovers are hitting harder and lasting longer. A big night out can leave me feeling flat for days. It’s not until now, my New Year’s Day nightmare, that I realise just how big a price I’m paying.

After texting Nat the numbers, I doze off for an hour or so, not ready to deal with all that a new year represents. A bad dream wakes me up with a jolt, and I lie there motionless, staring at the ceiling – too tired to move, too jumpy to sleep.

Then I feel it: the slow creep of panic. It starts, as it always does, with a tingling sensation around my heart, rising feverishly until it feels as if my heart might shatter or burst right out of my chest. Pins and needles run through my fingers. My feet turn to slabs of stone. My breathing is so laboured that I have to remind myself to inhale and exhale. I first began to suffer panic attacks as a teenager. Over time, I learned to control them to the point where they rarely bothered me, but recently they’ve crept back. Hangovers are often the trigger.

On this first day of 2011, the panic returns with a fury I’d forgotten. It comes in waves, racking my body and rising up to my brain with a rush of blood that makes my head sway. My heart, beating as fast as a champion racehorse, is so loud it’s all I can hear. I feel like I might pass out. Or die. Each surge brings more thoughts that trigger more waves of panic. What’s happening to me? Surge. I haven’t felt like this for years. Wave. Maybe I should eat something. Surge.

Even the idea of buttering toast is more than I can handle. But I’m light-headed and hungry. I throw on jeans and a T-shirt, and jump in the car to go to McDonald’s. Big mistake.

I make it out of my garage, and I’m at the traffic lights when it comes: a wave of panic so powerful that it takes all my strength not to run screaming from the car. Traffic is behind me, pedestrians are on the crossing, and I’m facing a red light. To my right, a metallic-blue Mitsubishi with tinted windows is pulsating to music that could best be described as angry noise.

As I turn the radio on to drown it out, the sight of my trembling hand triggers another wave of panic. The DJ bursts forth from the speakers, babbling about New Year’s resolutions and hangover cures. I can’t cope. I mash the buttons with the palm of my hand like an elephant trying to master a typewriter. Breathe. Remember to breathe.

The lights turn green and I turn left. I’ve only travelled a few metres when another wave threatens to run me off the road. I pull over into a side street, head between my legs, willing myself to keep it together. “You can do this, Starkers,” I incant, breathing slow and hard, in through my nose and out through my mouth, as I first learned when a petrified 16-year-old – half a lifetime ago.

I compose myself enough to continue the short drive. The panic seems to subside marginally when I’m moving; stationary, everything turns to custard. At the drive-through, I pray for a swift getaway. It’s not my day. The man in the car in front is ordering enough for a footy team. Fuck him and his four quarter pounders, six Big Macs, and three happy meals! Cars are backing up behind me – more New Year’s Eve casualties in search of just the right combination of fat, salt, and sugar to ease their pain.

Finally, the hungriest man in Melbourne finishes his order. When it’s my turn, I bristle at the sound of my voice. It’s distant and disembodied. The girl who takes my money is apprehensive. I wasn’t game enough to look in the mirror before I left the house, but I suspect it isn’t pretty.

Back home, I curl up on the couch, munching my foul-smelling meal like a rat gnawing on a bone. Still the panic comes, but the waves begin to lap more gently as exhaustion kicks in. I crawl back into bed around 9pm, the first day of a new year a complete write-off. I’m broken. No party is worth this much pain.”

‘High Sobriety: My Year Without Booze’ by Jill Stark (£12.99, Scribe Publications) is out now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments