‘Dine and dash’ is the new shoplifting – and we’re all paying for it

As it emerges that a couple from Port Talbot racked up over £1000 in unpaid restaurant bills, Sam Wilson looks at the growing phenomenon of people ‘doing a runner’ from restaurants and the impact it is having on restaurants and their bill paying customers.

The closest I’ve ever gotten to dining and dashing was in the pick ’n’ mix aisle of Tesco. I still remember locking eyes with a fellow customer as I took a piece of fudge, untwisted the wrapper and inhaled it – before covering the evidence in my palm in what felt like one incredibly slick move for a seven-year-old.

As the cost of living continues to keep most of us at arm’s length, my childhood sleight of hand has now become “du jour”, and more people than ever are getting in on the criminal act. Shoplifting is now at such high levels that it has been dubbed an “epidemic”, with thefts having doubled in the past three years, reaching 8 million in 2022 and costing retailers £953m, according to the British Retail Consortium.

A government survey from 2021 found that “food and groceries” were the most commonly stolen items (39 per cent compared with 33 per cent in 2018), and now the trend is transferring to restaurants themselves, with customers increasingly “dining and dashing” or doing a runner, as it was once “fondly” called when I worked in the service industry, confirming what I’d always suspected: people really are the worst.

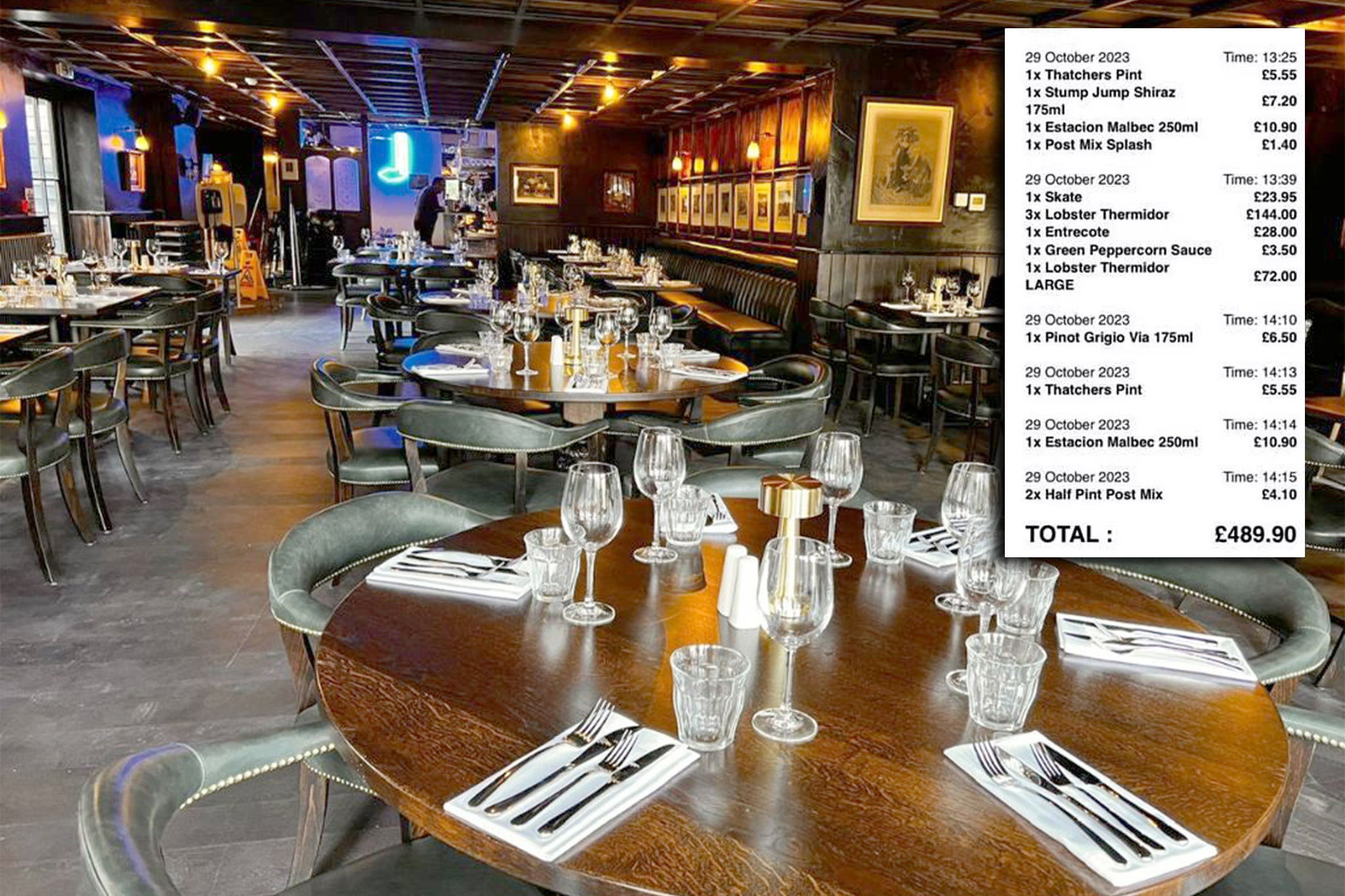

This week, Swansea Magistrates’ Court heard the five offences of a couple of ‘dine and dashers’ from Port Talbot who, over a number of months, racked up unpaid bills which totalled £1,168.10. Last October, a party of seven dashed in Kent after dining on a £489 meal, which included oysters and lobster thermidors. In Cornwall, a family of 12 attempted the same before being shamed into paying. In November , a gang of “posh pensioners” were at it at a Med-Mex restaurant in East Yorkshire.

The well-dressed foursome apparently chose the most expensive dishes on the menu and scarpered before paying their £96 bill. The devastated owner believes it was a carefully planned operation. Racha Eid, who runs the eatery with her husband Claude, said: “If you look at the CCTV footage before they leave, you can see them all looking at the till to see if any staff are there. They were planning this all along.”

Last summer, a family dined and dashed at the Fisherman’s Arms near Penzance, pretending to go out for a smoke and doing a runner on their £215 bill, which included three courses and cocktails – only returning to pay up after they had been outed on social media. One of the most extravagant cases of dine and dashing surely has to be the case of a newly married couple and their 80 guests who ran up a £7,000 bill on a seafood banquet at a restaurant in Boville Ernica in Italy. When the owner went to collect the money, they were found not just to have fled the restaurant, but they had done a runner from the country too. And what happens at weddings can also happen at funerals; that same month a party in America walked out on a sizable bill, threatening staff in the process.

A Barclaycard’s study found that one in 20 people have walked out without paying for their meal, and while some of this was put down to frustration of waiting for a bill to arrive, the trend for a deliberate dine and dash is causing considerable pain across an industry already struggling with the headwinds of Covid and economic turbulence.

Restaurateurs have already had to cope with no-shows, which have doubled in the last year, causing one in five restaurants to consider packing it in altogether as a result. Factor in the impact of cautious consumer spending, rising staff costs, and ongoing cost hikes for ingredients, drinks, and energy –an average of eight restaurant sites were forecast to close this year.

Not that any of this will stop the Dine and Dashers – a demonstrably contemptuous breed, sodden with indifference for those who feed us and anyone who actually pays, as these losses, of course, have to be recouped, inevitably expressing themselves in menu prices. Or skimmed from employee wages.

Restaurants are susceptible to abuse because the essence of hospitality is to accommodate, not challenge. Dine and dashers Trojan Horse this dynamic, deliberately misinterpreting kindness for weakness to actively exploit. As Kentarō Donovan, general manager of The Clifton in Bristol, has found.

“We had one couple who had booked in for a roast; they seemed lovely, very chatty and then just walked out. It was a busy service, and the couple thanked everyone and just walked out the door,” he says. “That’s why we now take deposits and card details.”

Of course, there’s the thrill factor, but there could also be something structural to blame, too, with the customer being seen as always being right – you can thank Cesar Ritz and Selfridges Harry Gordon for that notion. The idea of consumer infallibility has created a petri dish of conditions in which some of the worst qualities in a person are permitted to thrive. It’s the Yelp and TripAdvisor origin story, where punters relish taking advantage of a dynamic that seems lopsided, the idea that somehow it’s okay to say and do things that wouldn’t be tolerated otherwise.

Like any bad behaviour that goes unchecked, you end up with brats who not only have no idea about the value of things but essentially don’t care. Dining and dashing is really the evil relation to its freebie-demanding cousin – an entitlement that results in having a toddler-type meltdown with a free meal acting as a dummy. The belief that the customer is never wrong has caused legions of fully developed brats to feel not just validated but untouchable. James Stuart, owner of Tomo No Ramen (which easily beats seven shades of shoyu out of its peers), has experienced such outbursts first-hand.

“We had one guy who emptied his bowl on the floor after complaining it was cold after leaving it for 20 minutes. He demanded a full refund and threw a tantrum when I said no.”

The knock-on effect from this, is a kind of vacuous irreverence, particularly toward the service industry; a sense of righteous entitlement that has mutated into treating the concept of food being made for us as a right, rather than the privilege it is. You’ve seen them – the kind of customers that start their sentences with “can’t you just” and “I know you’re not serving breakfast anymore, but...”

The apologists among you will say that these people are simply “sticking it to the man”, that they’re Davids to the Goliaths of capitalism and restaurants charging high prices for what you can make for a third of a price at home are “fair game”. But these people aren’t stealing from JP Morgan Chase or even McDonald’s – instead, they are taking from small, privately owned restaurants for which every penny counts.

Dining and dashing is the ultimate cringe because everything about it is a choice. It views hospitality as a series of loopholes and hacks through the lens of some overdue servitude, biting the hand that feeds, fully intent on drawing blood with a view to a laugh. It’s what makes The Bullingdon Club such a colossal cyst. As restaurants face quadrupling tax bills amid all the existing pressures, those who skip the bill are pickpockets to us all who do the decent thing and pay.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments