The cult of the skinhead: Where are the buzz-cuts now?

As a new exhibition examines the skinhead subculture, Tim Willis remembers the bootboys who terrorised 1970s society and wonders where they went

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

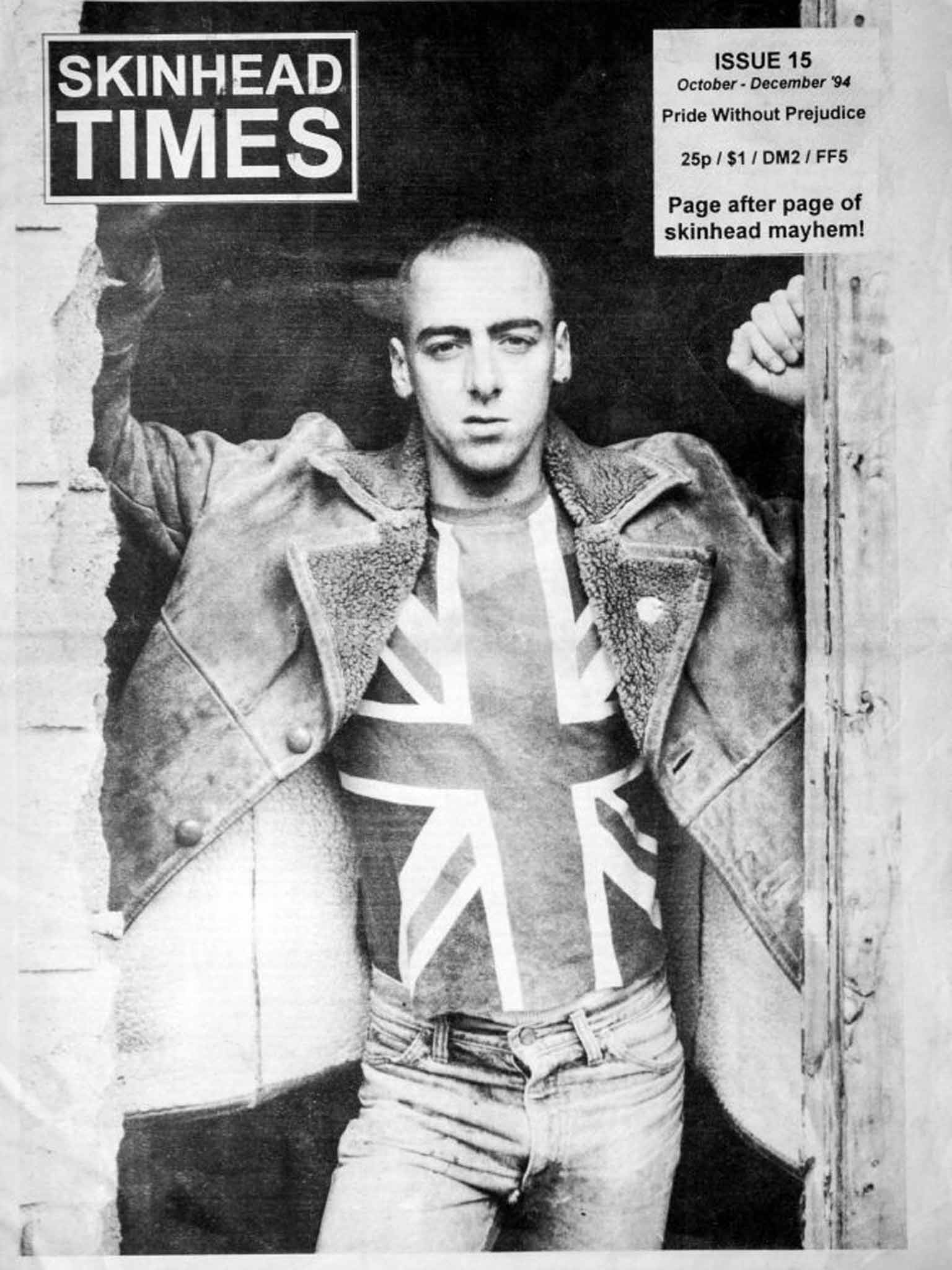

Your support makes all the difference.Was ever a youth tribe less loved than the Seventies' skinheads? With reason. Though their buzz-cuts and Doc Martens have now been appropriated into acceptable society, a version of their uniform – generally topped by a flight jacket – is still regulation issue for far-right thugs around the world. And if at the time of their rise in Britain you were a middle-class teenager with a fuzzy creed based on the platitudes of long-haired rock stars whose style you tried to ape, you'll know the very real fear you felt at the sight of them.

I grew up in genteel Harrogate, and I remember the day the Leeds Clockwork came to town. These guys had given Clockwork Orange a bootboy-makeover, and Christ, they were frightening: baggy white jeans, shortened to display 14-lacehole Cherry Reds, collarless white shirts and braces, eye liner, a bowler hat here, a stout cane there.

There were about a dozen in this raiding party. Emerging from the train station, they split up in pairs, causing us to rush into the cafés where we gathered to tell breathless tales of street chases. It was not a day to wear an Afghan coat.

But as suddenly as they arrived in town, they disappeared – and the same could be said of their subculture. Suedeheads, Crombies and casuals lingered for a while, but the skinhead attitude – best summed up by the Millwall chant, "No one likes us and we don't care" – soon morphed into the nihilism of non-commercial punk. Then the free market took over, society fragmented, the population rebalanced and the idea of "youth movements" began to seem faintly ludicrous.

Today, with the distance of time, one can feel almost sorry for the poor creatures who started skin-dom. They were working-class white boys, left high and dry by a society that had less and less need for a working class. Those who had still jobs – mainly in industry and manual labour – dressed for efficiency and safety, not effect. Immigration, pacifism, feminism; the forces swirling around them were bewildering and alienating. Fearful, they could choose between flight or fight – and with some swagger, they chose the latter.

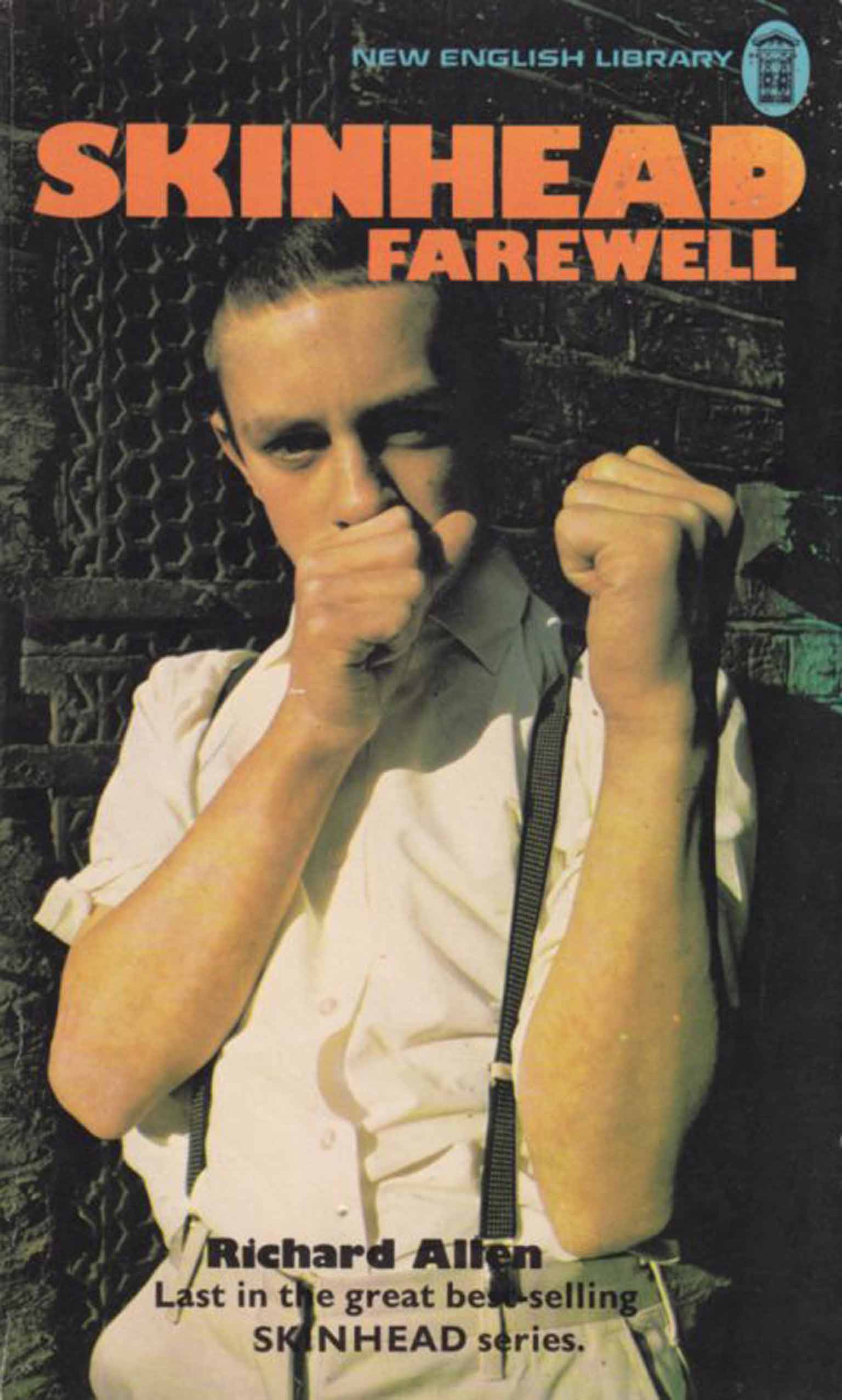

Now they're being remembered in a thoughtful book of illustrated essays and an accompanying exhibition, with all visual material curated by the designer and pop-culture historian Toby Mott (who sported a buzz himself 30 years ago, as a member of the arty Grey Organisation).

Here you'll find all sorts of variations and themes explored. Was the style's gay appropriation subversion, self-protecting camouflage or fetishisation of the oppressor? How ambivalent was the relationship between the skins and working-class black culture, as expressed in ska and Northern soul? What values was Weetabix trying to promote with its loveable cartoon bootboys in the early 1980s?

But the focus of both book and show is the classic British skinhead – who Mott describes as "just great". They may have been simplistic, he says, "but they knew what they stood for". As for their politics: "You may not like organisations such as the BNP, but they're not illegal.

"Sure," he continues, "Combat 18 [the far-right terrorist group] was formed by ex-skinheads, who were dreadful people, but the whole Midlands two-tone movement was, too." And what's wrong with a bit of patriotism? "There's something rather magnificent about a bunch of drunken skins, stripped to the waist outside a pub, shouting, 'No surrender to the I-R-A'!"

What the skins had, says Mott, was pride in themselves and their communities, and that gave them a certain dignity: "These guys weren't aspirational or out for what they could get. They were seeing their way of life disappearing and, as they saw it, defending it. They weren't apathetic thieves and small-time gangsters like the hoodie underclass of today. A hundred years before, they would have built the Empire."

Today, says Mott, there isn't really a skinhead scene. Like old Teds and scooter boys, they have their Facebook groups and reunion outings. But by and large, they grew up and got real. As far as Mott knows, they didn't go on to be particularly active in nationalist politics – although one of the book's contributors, Joseph Pearce, was prominent in the UK National Front's youth wing, published its magazine (which landed him in prison for racism) and was associated with extreme right-wing figures well into his twenties.

In 1989, Pearce converted to Catholicism. He now takes his religion very seriously, and is director of the Centre for Faith and Culture at Aquinas College, Tennessee. Which is somehow almost as frightening.

'Skinhead – An Archive' (£38) is published by Ditto Press tomorrow. The accompanying exhibition is at Ditto, 4 Benyon Road, London N1, from 12 December to 22 January

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments