Stealing style: Why appropriation is always appropriate in fashion

Back in 1996, Alexander McQueen approached the war photographer Don McCullin about reproducing his images on clothes. McCullin refused. McQueen did it anyway

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Appropriation and misappropriation have been major sources of ruffled feathers in 2015. Most memorably, there was a furore over the fine artist Richard Prince's work, itself dubbed “appropriation art”.

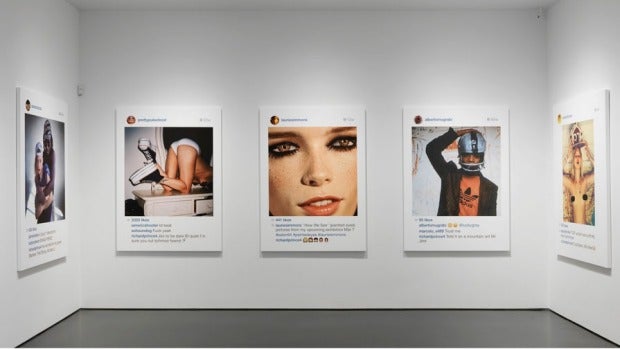

In 2014, he staged a show at the Gagosian Gallery in London titled “New Portraits” – new in the sense that they hadn't been seen before and that the medium in which they were created seemed new.

The portraits were grabbed from Instagram, appropriated from other people's accounts – including those of the singer Sky Ferreira and the Victoria's Secret model Candice Swanepoel – then printed on canvas. Some loved it, some hated it, but it was restricted to arty discussion. Then, said images were put on sale at New York's Frieze art fair in May. Their prices hovered around the $100,000 mark, which of course attracted far more indignant attention than the earlier show.

Fashion is a fan of appropriation – not copying, because to copy means to counterfeit, but the lifting of someone else's work in whole or part without due credit – and generally, unintentionally. Last October, for example, Balmain's Olivier Rousteing was taken to task over a spring/summer design that resembled rather too closely a suit from Alexander McQueen's 1997 debut collection for Givenchy. (Remember that? Not many people did – and maybe Rousteing thought the same.) But, in turn, Rousteing has appropriated his own work: his collection for H&M offered near-facsimiles of Balmain catwalk looks, a wardrobe of Balmain greatest hits for a fraction of the retail price.

Authorship is key to this kind of appropriation. If H&M had ripped off Rousteing, for instance, it would have been an issue: but to reference yourself is acceptable. Miuccia Prada did it superbly for her Miu Miu Resort collection, including a print from a 1996 advertising campaign patched across the back of jackets and dresses.

That's the simplest act of appropriation: a print. Back in 1996, Alexander McQueen approached the war photographer Don McCullin about reproducing his images on clothes. McCullin refused; McQueen did it anyway. And I'm a fan of that sort of appropriation, I like two-fingered salutes such as McQueen's.

Those fingers are also up to the current lust for collaboration, particularly of the arty-farty variety – as Prince famously did with Louis Vuitton. Not that I especially like his “New Portraits”. I do, however, like how one of the individuals whose images Prince appropriated – Selena Mooney of the website SuicideGirls – is offering her own ersatz Prince prints, for $90 – rather less than Prince's $90,000 price tag. “Beautiful art, 99.9 per cent off the original price,” she says. How about that for an H&M tagline?

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments