No new blood and no fresh ideas at Milan Fashion Week: How do you solve a problem like Milano?

How can the staid and struggling Italian clothing industry be transformed, asks Alexander Fury

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The Milanese leg of the spring/summer 2015 international collections will limp to a close tomorrow, but most of the world’s press and buyers will fly out of the city today. Why? Well, why not? There’s nothing to stay for. Milan Fashion Week is contracting, compressing.

This season, the main shows are across five days rather than six, after a number of influential editors (Anna Wintour of American Vogue being the most important) didn’t stay for Monday’s shows last season. The major show that day is traditionally Giorgio Armani, a heavyweight anchor to moor press and buyers in the city while other, lighter labels flounder. But this season Armani moved his show to Saturday, despite a press conference after his autumn/winter 2014 show in February when he lambasted both the American Vogue editor-in-chief and his Italian counterparts. “There are some who prefer to snub the Giorgio Armani show and go to Paris,” he said. “When we decided to show the last day, other big brands were involved. But currently this is an empty day … Does this mean protecting Italian fashion?”

His concerns seem justified. Milan’s importance could be slipping. And despite a clutch of well-received collections – Prada, a strong and vibrant Versace, Bottega Veneta’s intriguing wrapping and layering – last week was a far cry from a past when Milan head-butted Paris for the dominant position in international fashion (and, at one point, appeared to be winning).

Some of the problems with Italian fashion today are part and parcel of wider issues. This year, Italy is experiencing its third financial downturn since 2008, according to the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. The economy, the third largest in the eurozone, has shrunk by 0.4 per cent in 2014 – and while the revenue of the fashion industry bucked the trend to grow 3 per cent, according to information released earlier this month by the Camera Nazionale della Moda Italiana (which organises and promotes the country’s fashion industry), it is well below a “great leap” originally estimated.

The reflection of that in high fashion isn’t just a certain timidity and uncertainty of design. The Prada group, which also operates Miu Miu, Church’s and Car Shoe, and presented its mainline range on Thursday evening, posted a drop in net profits of 20.6 per cent in the first half of the year. Patrizio Bertelli, its chief executive, stated that “the difficult economic and geopolitical conditions are negatively influencing consumers’ attitudes”. Listed on the Hong Kong stock exchange since 2011, the company’s shares fell 1.3 per cent to their lowest level in more than two years.

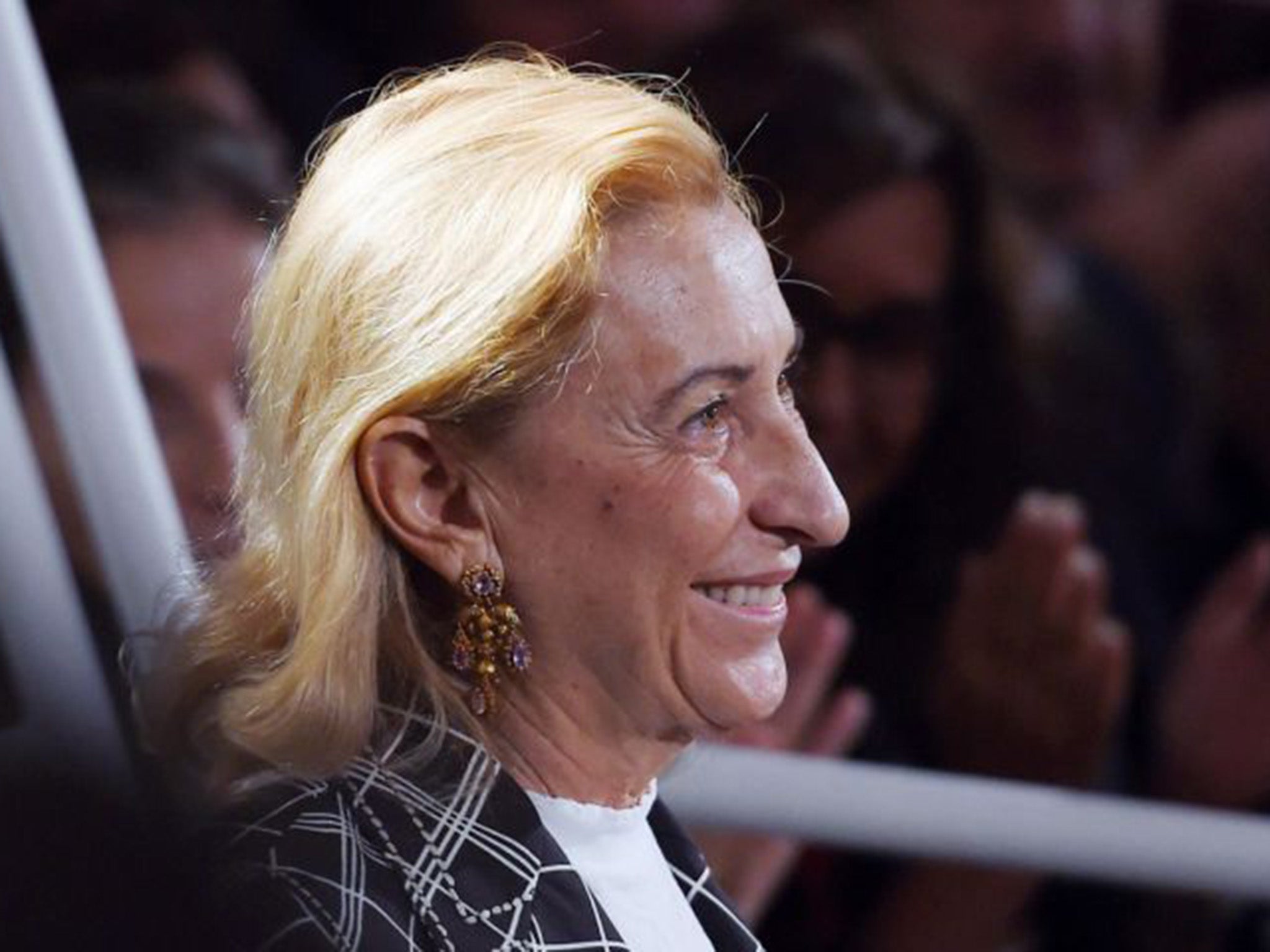

It’s disquieting to hear such reports from Prada, a consistent over-achiever on the stock market and jewel in the crown of Italian fashion. “It’s a one-show week,” as an American editor commented. She was referring to Prada, and she was sort-of right. Miuccia Prada’s spring/summer 2015 show, devoted to craftsmanship, the “accident of the hand and the perfection of imperfection” – meaning reversed brocades, patchwork, raw hems and inside-out seams – was an undoubted and unequalled highlight.

That collection was compelling, yet oddly commercial – as Prada’s always are. However, it will be sold in fewer than expected stores next year. “We will have net openings of 65 stores against 80 planned,” said Donatello Galli, Prada’s chief financial officer, announcing a cost-cutting effort to protect margins.

These are worrying reports for anyone – and, as in politics, economic depression leads to conservatism on the catwalk. That’s perhaps why we’re seeing recycled ideas in abundance. Or perhaps it’s just a lack of creativity overall?

You felt it at Giamba, the new label launched by Giambattista Valli, an Italian-born designer who lives in Paris where he also shows his mainline ready-to-wear and haute couture collections. For a secondary line by a non-advertising brand, there was an impressive turnout.

The same was true for Marco de Vincenzo, a Sicilian-born former Fendi designer who started his own label in 2009.

“He’s the Italian Christopher Kane,” murmured one editor excitedly. And indeed, De Vincenzo picked up a considerable amount of buzz last season when LVMH invested in his label prior to his winter show. But this collection, all fringe, crystal and flappy fabric experimentation beneath strange raffia hats, felt wrong-footed atop heavy, dated, platform shoes.

Neither did Giamba set the world alight, with its glitter and crystal heels, baby-doll dresses and heavy reference points. Miu Miu is derived from Miuccia Prada’s nickname, Giamba from Valli’s. Is that why they looked so similar?

It was an inauspicious debut – but it was something new, in name if not in design. And that was the motivation for attendance, pure and depressingly simple. The same with De Vincenzo – who, on the strength or otherwise of this collection, is no Kane.

Milan fashion week frequently feels stagnant, age-old and old age. Armani celebrated his 80th birthday in July, and his label turns 40 in 2015, which also marks the year Karl Lagerfeld will have designed for Fendi for half a century.

Compare that to the crop of newcomers in London or New York, or the fresh talent in place in houses in Paris, and age becomes an issue. Where’s the new blood? The new ideas? That is what will make press stay, and consumers buy.

Could old age, then, cause the natural death of Italian fashion? Maybe, if there’s no transfusion of the talent that is sorely needed.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments