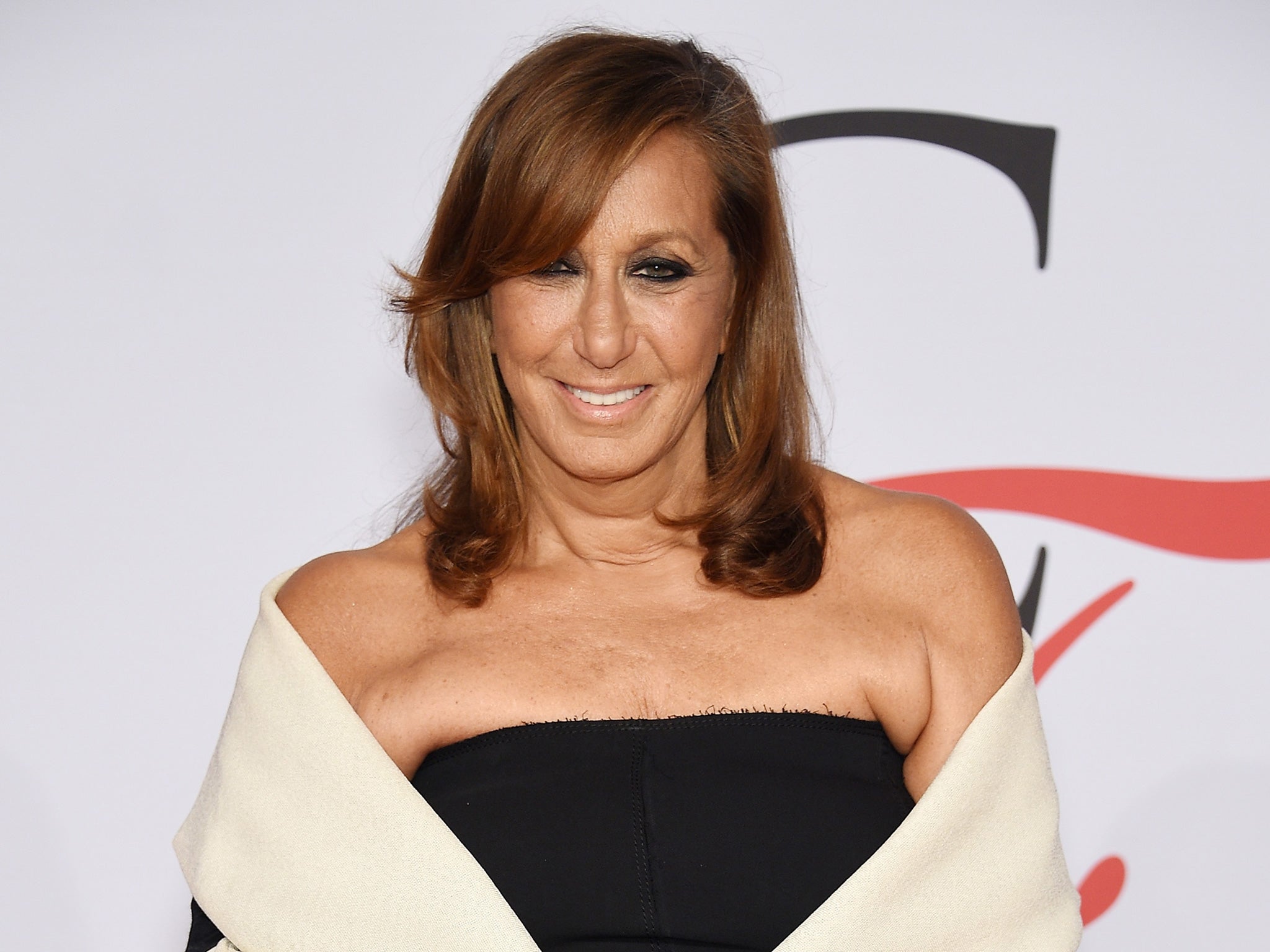

Donna Karan: Your name may be on the label, but it doesn’t mean a job for life

The designer left her label on Tuesday, saying that it was her choice

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.What’s in a name? Well, when you’re a fashion designer and you don’t own your own name, quite a lot. What it means is that, although your name is above the door, you’re a hired hand, and can be booted out if – or when – the bosses decide your time is up. That’s sort of what has happened to Donna Karan, who left her label on Tuesday. Karan says that it was her choice, but there had been strains showing in her relationship with the luxury conglomerate LVMH, who took control of the brand in 2000. They closed her Madison Avenue flagship, and Karan herself once stated that she felt that they had given her “the cold shoulder” – a neat reference to the chopped-out evening dress that was one of her signatures.

Karan’s situation isn’t unique: designers from Halston through to Roland Mouret have lost control of their companies, then suffered the ignominy of seeing designs that they would never have approved of executed in their name. The designer Tom Ford once stated that he would never start an eponymous label for exactly that reason (although he’s since very publicly reneged). Karan doesn’t have to worry, because they won’t be carrying on her namesake label. At least, not the one that sports her full name – but her DKNY collection will continue to be shown, under the creative direction of young upstarts Dao-Yi Chow and Maxwell Osborne of the label Public School.

Still, Karan has been removed from that for a while, allowing a separate team to come up with the goods. But maybe that’s even more upsetting: seeing your name relegated to the scrapheap of history; or – worse still – the sale rail. And it raises a question: why would designers sell their names in the first place?

Obviously, there’s the monetary value – Karan publicly listed her company in 1996, while the LVMH takeover netted her approximately $400m – and that must be some solace. And for the smaller guys – such as Christopher Kane, who is majority owned by the Kering group, or the recent LVMH additions Nicholas Kirkwood and JW Anderson – an injection of conglomerate cash gives them the opportunity to propel their businesses into the big league.

Just two years after Kane’s Kering coup, he now has a jzushy store on London’s fashionable Mount Street, crammed with commercially crafty accessories and expansive pre-collection lines geared to sell. At least, Kane and his fellow conglomerate cohorts hope so. If they want to keep their jobs, and their names.

But I always remember what the shock-designer Rick Owens once said to me: “I don’t have to do anything I don’t want to. It’s not like I’m obligated to make any compromises.” Because he’s independent, he said, he “could just burn the whole fucking place down”.

He won’t, of course. But it’s important to Owens that he could.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments