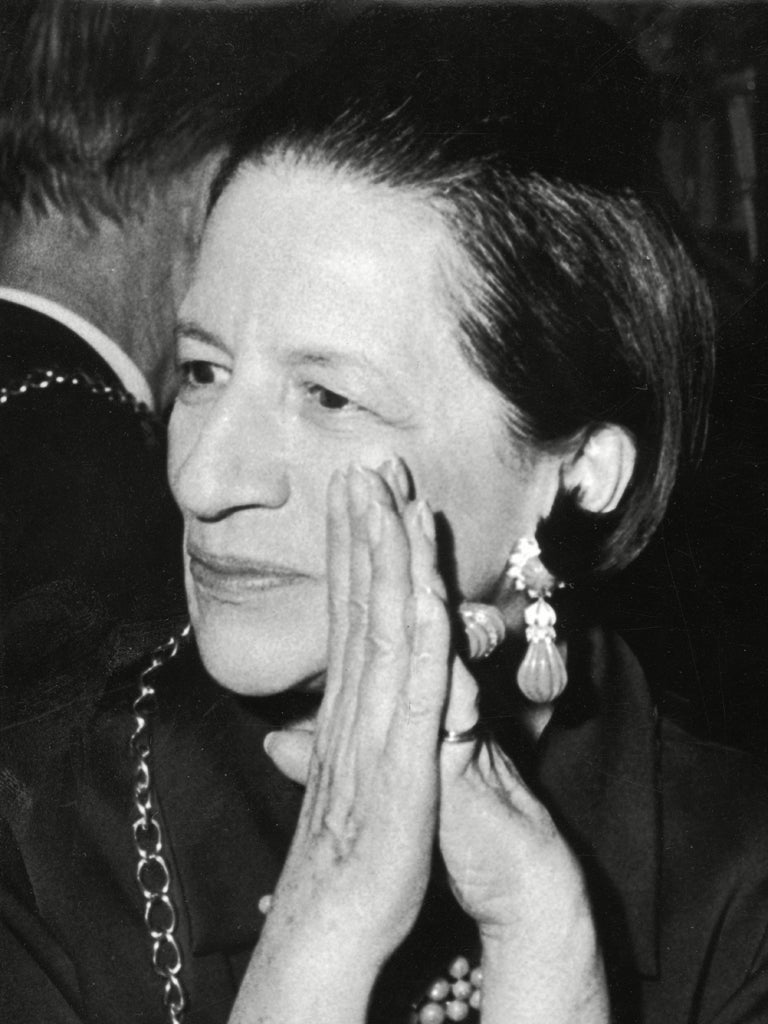

Diana Vreeland: A sacred monster

A new documentary about the legendary Vogue editor Diana Vreeland reveals how her unparalleled drive and perverse taste changed the face of modern fashion. Geoffrey Macnab meets the director

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference."She was never a very rich woman, she was never a very beautiful woman and yet she created beauty and she created wealth," an observer notes of Diana Vreeland, the legendary Harper's Bazaar and Vogue editor whose story is told in new feature documentary Diana Vreeland: the Eye Has to Travel.

Vreeland (1903-1989) was one of the sacred monsters of the fashion world: a magazine editor who used to browbeat her photographers and models; who never deferred to her publishers or advertisers and who approached each new issue of her magazines with a messianic zeal.

Don't suggest to Lisa Immordino Vreeland (the director of the new film) that her grandmother-in-law's chosen world was superficial. Immordino Vreeland contends that "Mrs Vreeland" (as she respectfully calls her) was a fashion revolutionary: a career woman who changed the way women dressed while also transforming the world of magazine publishing. According to the director, Vreeland also created the modern-day fashion editor. Before she arrived, fashion was the domain of "society ladies" who would offer advice on how women could please their husbands or cook a nice pie.

Vreeland was the one who discovered Lauren "Betty" Bacall (long before Howard Hawks cast her in To Have and Have Not and The Big Sleep) and was responsible for Jackie Kennedy's "look" during JFK's early days at the White House. She was the high priestess of exoticism. "She had a taste for the extraordinary and the extreme," Anjelica Huston says of her on camera. "She would go anywhere," a photographer notes, claiming that Vreeland would have arranged photo-shoots in outer space if her publishers had allowed it.

For all her extravagance, Vreeland also possessed the common touch. An early champion of denim and of bikinis, she brought colour and fantasy into readers' lives as well as images of clothes they could conceive themselves wearing.

It's striking how terrified of Mrs Vreeland so many of her former colleagues remain. For example, Ali MacGraw, who worked as her assistant in the days before she became a movie star, talks with evident alarm of Vreeland "storming into the office" and barking out orders. MacGraw portrays a character altogether more terrifying than Anna Wintour, the current editor of Vogue, or the Wintour-like magazine editor played by Meryl Streep in The Devil Wears Prada. On one occasion, Vreeland returned to the office after lunch and hurled her coat at MacGraw, expecting the assistant to hang it up. Instead, MacGraw hurled it back. Vreeland was furious but also admired her assistant's gumption.

Invariably, half her staff was reduced to tears before the day was over. Even so, they grew (and remained) devoted to her. Immordino Vreeland contends that Vreeland's intimidating persona is one reason why no films have been made directly about her now (although she is referenced in everything from Stanley Donen's Funny Face to Douglas McGrath's Truman Capote drama Infamous.)

The Eye Has to Travel is one of an increasing number of feature documentaries about formidable figures in the fashion world. These docs have certain traits in common. They're unashamedly nostalgic, evoking a lost world of couture and glamour. Their central characters (whether designers like Valentino or editors like Vreeland) are exotic and eccentric figures. Their private lives are shadowy and they only really come to life when they're working.

"Why don't you paint a map of the world of all four corners of your boy's nursery so they won't grow up with a provincial point of view... why don't you wear violet velvet mittens with everything," the precocious nine-year-old Olivia Vreeland suggested midway through my interview with her mother, Lisa. These are snippets of Diana Vreeland's journalism in the 1930s, when she started her career writing a "why don't you column" in Harper's Bazaar. They're included in the film and Olivia can still recite them perfectly. Such brittle and witty one-liners seemed frivolous as the Second World War broke and Vreeland stopped the column.

However, watching the film, you begin to suspect that the "why don't you" columns weren't entirely tongue in cheek. In the rarefied world that Vreeland inhabited, washing your blond child's hair in dead champagne to keep its sheen ("like they do in France") was probably what passed for common sense. Lisa Immordino Vreeland, a designer and former fashion PR, never actually met Mrs Vreeland but is so steeped in her life that she arguably knows her much better than either her relatives or old colleagues. "I got to know her through my research," the director (who pored through 26 years worth of Harper's Bazaar and nine years of Vogue as well as records of Vreeland's controversial stint as consultant at the Costume Institute of the Metropolitan Museum of Modern Art.)

More than 40 "talking heads" feature in the documentary, among them some of the most celebrated names in the fashion world. What is startling is how differently her family and her colleagues remember her. To her sons, she was an absentee mother. They testify how they wish she could have been just an ordinary parent, like the ones their school friends had.

Immordino Vreeland's primary interest is in "the professional side" of Vreeland. The relatives dutifully appear on camera, talking about her with a mix of bafflement and affection but the director doesn't want to probe too deeply into her family background or Diana's relationship with her husband. Her childhood is skimmed over although it's hinted that her drive to succeed came from her difficult relationship with her mother, a society beauty who scorned her as the ugly duckling of the family.

"In her autobiography, she [Vreeland] talks about the fact that her mother called her 'her little monster'," the director recalls. "She had a beautiful younger sister who was her mother's favourite. She said, 'Well, I've got to become an original because if my looks are not going to bring me somewhere, I've got to be original in thought, style and the way I express myself.'"

The director contends that Vreeland's style was "actually quite classical." In spite of her own (slightly ghoulish) appearance – tight skull cap, dyed jet-black hair – she believed above all in elegance.

Just occasionally, the documentary hints at its subject's vulnerability. Vreeland had had almost no formal education. She was such an intimidating presence that few would challenge her. However, she had her knock-backs. She was fired from Vogue and overlooked for the top editorial position at Bazaar. When she was organizing costume exhibitions at the Met, other curators questioned her academic credentials. The Queen Bee was in her element when she was editing a magazine but was a forlorn and diminished figure when she was between jobs and trying to adjust to "ordinary" life.

Unlike many fashion editors and commentators today, Vreeland was open to the world outside the hot-house atmosphere of the shows and the catwalks. She thrived in the 1960s, embracing pop culture, civil rights and the new permissiveness. British photographer David Bailey testifies that she was the first to publish a picture of (a then little-known) Mick Jagger in a fashion magazine. Under her stewardship, the pages of Vogue featured not only Twiggy and Jean Shrimpton but Maria Callas, Luchino Visconti, Alexander Calder and Truman Capote. Vreeland was always drawn to the oddball: if models were very tall (like Veruschka von Lehndorff) or had irregular features, she would pick up on it. "If you have a long nose, hold it up and make it your trademark" was her attitude and explained why she featured Barbra Streisand as a model, emphasizing her "Nefertiti nose."

The elegiac quality in The Eye Has to Travel is self-evident. "Those [the 1960s] were the golden years of Vogue," the director states. "Before, it was very much a society magazine but she brought life to it. She brought culture, she brought interest... they really covered art, culture and literature."

'Diana Vreeland: the Eye Has to Travel' will be released in the UK later this summer

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments