Australians rediscover the 'million dollar mermaid'

Annette Kellerman's design gave women the freedom to swim – but not without controversy. Kathy Marks reports

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Dubbed Australia's mermaid and "the perfect woman", Annette Kellerman was a household name a century ago, in Britain and the US as well as at home. But the marathon swimmer, vaudeville performer and silent movie star faded from view and nowadays she has been all but forgotten, even in her own country.

Yet Kellerman was a role model for a generation of women, transforming their perceptions of themselves and liberating them from 19th century constraints. While her main contribution was a practical one – she designed a swimsuit in which the wearer could actually swim – she also influenced the way women behaved and helped create a modern notion of femininity for the 20th century.

Kellerman is the centrepiece of a new exhibition in Sydney which traces the evolution of swimwear over the past 100 years. Curators say that it is already re-igniting interest in the woman that one modern commentator has called the Madonna of her generation.

Kellerman's story is an extraordinary one. Born in Sydney, she was crippled by rickets as a child and took up swimming to strengthen her limbs. By the time she was 16, she held the world record for a woman's 100-yard swim. Aged 18, she sailed to England, where she made three attempts to swim the Channel and swam 26 miles down the muddy Thames for five hours, dodging tugboats and swallowing "what seemed like pints of oil". After she raced 17 men along the River Seine in Paris and finished third, the newspapers asked: "How can a woman do this?" Kellerman replied: "What a man can do, a woman can do."

But sport was not the only realm in which she excelled. Her theatrical flair propelled her on to the vaudeville circuit, where, dressed in a range of revealing costumes, she performed acrobatic feats in tanks of water. She then went to the US and starred in 12 silent films, including Daughter of the Gods, which with its $1m (£610,000) budget was at the time the most expensive film ever made and also featured the first nude scene by a major actress.

In 1908, a Harvard scientist, Dr Dudley Sargent, examined 3,000 women and, finding Kellerman's measurements to be almost identical to those of the Venus de Milo, declared her "the closest to physical perfection". That was Kellerman's launchpad for yet another successful career: as a promoter of women's health and fitness.

It was as a designer, though, that she had the most tangible impact. At the time, it was customary for women wishing to immerse themselves in the sea to wear cumbersome woollen bathing dresses, together with bloomers, stockings, caps and shoes. Such outfits were impossible to swim in; indeed, they were so heavy when wet that they were positively dangerous, particularly when weights were placed in the hems to prevent skirts from billowing up. Drowning was a real hazard.

Men, by contrast, wore one-piece sleeveless bathing suits, which were much more functional, so Kellerman decided to invent her own version, with tights attached. The result was a costume that covered the wearer from neck to toe but was scandalously figure-hugging – and people were duly scandalised. Kellerman was undeterred, and the suit became her trademark. In 1907, she was arrested while strolling along along a Boston beach in a thigh-length creation.

Women quickly adopted the men's-style suit, particularly for competitive swimming. "She created a new look for women, but she was also making a very strong statement that women could be active and glamorous," says Penny Cuthbert, the co-curator of the exhibition, "Exposed! The story of swimwear", at the Australian National Maritime Museum.

Cuthbert says: "The restrictive bathing costumes of the time mirrored day wear, with its corsetry and voluminous skirts, so Kellerman influenced not just swimwear, but the whole way that women behaved. She really broke the mould in terms of how women were expected to be, and she gave them not just freedom in the water, but freedom to be active in all kinds of ways."

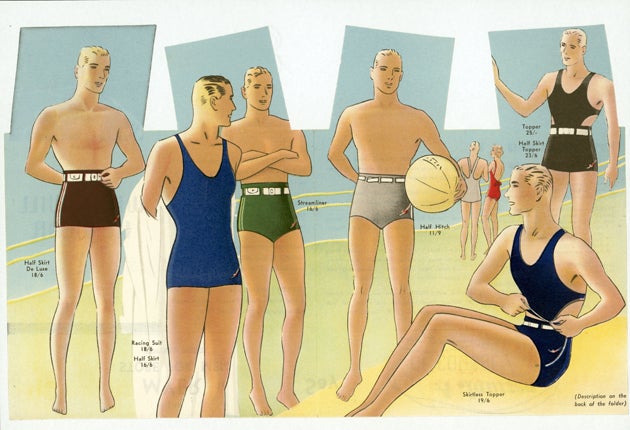

If practicality was one of Kellerman's mottos, that concept also underlies Australia's wider contribution to swimwear. It was an Australian company, MacRae's Knitting Mills, that created the Speedo range, launching the men's Racerback swimsuit in 1928 and the now ubiquitous Speedo briefs in 1960. Much easier to swim in than a costume with traditional straps, the Racerback became a design classic.

The briefs, meanwhile, sat on the hips rather than the waist, permitting greater freedom of movement. Until then, men had worn high-waisted trunks that chafed and rubbed when they swam. The designer of the briefs, Peter Travis, had been asked to come up with a garment akin to boxer shorts. But he rebelled. "I wanted to create a swimsuit that you could swim in," he recalls. "They [the briefs] were designed wholly and solely for function".

They took a while to catch on: the first men who modelled them, at Sydney's Bondi Beach, were arrested and frogmarched off the beach, just as Kellerman had been in Boston. Some people still find them hard to stomach: earlier this month, Britain's most popular theme park, Alton Towers, banned men from wearing Speedo's and other skimpy trunks, in order "to prevent embarrassment among fellow members of the public and to maintain the family friendly atmosphere at the resort".

Even greater controversy surrounds Speedo's latest high-performance bodysuit, the LZR Racer, which sent records tumbling at the Beijing Olympics. Last month, world swimming authorities banned all body-length swimsuits from 2010. (Speedo, much to Australians' chagrin, is now British-owned.)

Kellerman, of course, was the first to favour such body-length swimming costumes. As Cuthbert says: "She was a bit of a trailblazer." In her films, she played mermaids and action heroines. In 1952, Hollywood made a film about her, Million Dollar Mermaid, in which she herself was played by the former US swimming champion Esther Williams.

Williams broke her neck while executing a swan dive from a 115ft tower and filming of the movie had to be suspended for six months.

Kellerman never made the transition to spoken films, which is one reason why she is so little remembered. Instead, she returned to the stage and re-invented herself as an expert on health and fitness. She gave lectures on the subject, offered correspondence courses and published a number of books, including one entitled Physical Beauty and How to Keep It.

Cuthbert believes Kellerman played a significant role as an early women's liberationist. Her attitudes were in stark contrast to those of, for instance, Rose Scott, the president of the New South Wales Swimming Association. Scott was a leading suffragette but was vehemently opposed to Australian women competing at the Stockholm Olympics in 1912. Cuthbert explains: "She was against them swimming in revealing costumes in front of men".

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments