What’s gone wrong at Asos – and can its identity crisis be fixed?

Business boomed for the fast-fashion giant during the pandemic, but now Asos is struggling with sluggish sales and a pile-up of old stock. Katie Rosseinsky asks if the brand’s current efforts to turn things around are enough to save the beloved online shopping platform

Your support helps us to tell the story

This election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

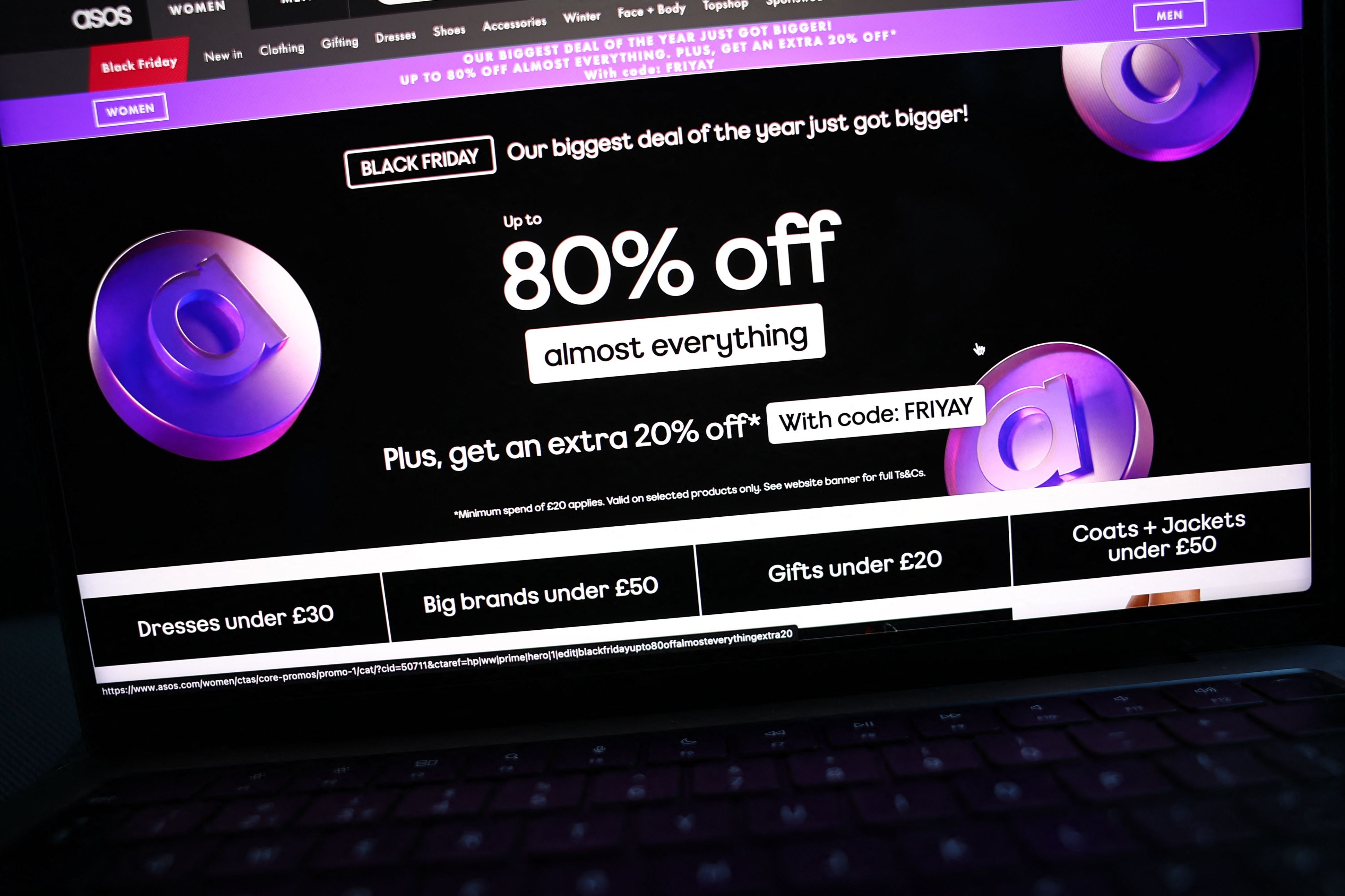

Every day, without fail, my phone buzzes with a new plea from the Asos app, like messages from an increasingly needy frenemy. “Hey queen!” they often shout, or “hey gorgeous!”. Then they get down to the serious business of sharing money-off codes of ever-increasing percentages, or pointing in the direction of last, last chance (no really, it’s the end!) sales. Couple these constant discounts with an overwhelming array of clothing to sift through (including past-season styles) and it feels like the online shopping giant has lost its way.

Behind the scenes, the numbers paint a similarly gloomy picture. Earlier this month, the company revealed an 18 per cent decline in sales in the first half of its current financial year, compared to the same period one year ago; its underlying pre-tax losses were £120m, up from £84.7m year on year. It’s another blow for the brand after it reported a 10 per cent drop in turnover in November. Bosses have suggested that this downturn is an inevitable (but, they hope, short-term) side effect of “necessary action” to overhaul the brand, like their ongoing drive to clear out their backlog of old products and to cut down on newer stock levels by around 30 per cent. CEO José Antonio Ramos Calamonte says he feels “confident” that from next year, Asos will “have the right level of newness to excite our customer again”. But is this just wishful thinking from the brand that once seemed to have cracked the online fashion code?

Asos wasn’t always a sprawling fast-fashion machine. It started life in 2000 as As Seen on Screen, a website dedicated to selling affordable versions of clothes sported by celebrities (its abbreviated name arrived in 2003). Think “sheepskin boots in the style of Kate Moss” – aka off-brand Ugg boots – and copycat versions of anything Alexa Chung ever wore. In 2004, the brand launched its own original womenswear label. Back then, ordering a dress off the internet from a brand you hadn’t previously encountered on the high street felt like a real leap of faith. But it didn’t take too long for Asos’s in-house designs to make waves. The clothes were trend-led, usually aimed at shoppers in their late teens and twenties, and tended to have a pretty decent price-to-quality ratio.

Eventually, their designs were spotted on stars like Rihanna and Katy Perry: the brand that began as a marketplace for celeb copycat pieces had come full circle. And in 2012, Asos had another major moment in the spotlight when then first lady Michelle Obama was photographed wearing its own-brand red chequered sundress while campaigning for her husband’s re-election. It wasn’t just all about the clothes, though. A speedy next-day delivery service (and the “Premier” subscription, allowing you unlimited access to this for just under a tenner per year) and free returns also helped establish it as a go-to for last-minute wardrobe emergencies.

There were, of course, a few wobbles along the way. In 2013, a batch of studded belts had to be quickly withdrawn from sale after they were found to be radioactive, testing positive for the isotope Cobalt-60. And five years later, the company issued a shock profit warning, blaming “economic uncertainty” in the wake of Brexit and unseasonably warm weather; the news briefly prompted their shares to tumble. Soon afterwards, Asos revealed that it’d be looking out for serial “wear and return” offenders who’d repeatedly make big orders then send everything back.

The pandemic proved to be a turning point. While many high-street fashion brands struggled as shops closed their doors during lockdown, Asos’s sales skyrocketed thanks to the online shopping boom (there wasn’t much else for us to do to relieve the tedium of being confined to our own four walls). Hoodies, leggings and tracksuits were all reliable performers. Its active customer base rose from 1.5 million to a staggering 25 million, and profits tripled year on year. By the start of 2021, things were looking so rosy that the company bought the iconic Topshop and Miss Selfridge brands following the downfall of Philip Green’s Arcadia Group.

So when the brand reported last year that sales were on the slide, it came as a surprise to the average shopper: how had its fortunes seemingly changed for the worse so quickly? Times are certainly hard for retailers. Many are still feeling the impact of Brexit, which has made supply chains more convoluted and expensive; the rising cost of living has also prompted many of us to scale back our spending. But beyond those usual suspects, there are a handful of more specific reasons why Asos might be struggling right now.

The millennial shoppers who were among the first wave of Asos devotees are now in their thirties and beyond. Ageing in and out of fashion brands is inevitable: if you’re yet to walk into a Marks & Spencer and think, “yeah, I’d probably wear that”, know that your time is coming sooner than you think. But Asos doesn’t seem to have properly captured the imaginations of the Gen Z customers who are now the brand’s target audience: their attention seems to be elsewhere. “Previously, Asos was the go-to for quick access to fashion micro-trends,” notes Briony Lewis, senior behavioural analyst at consumer insight agency Canvas8. But the rise of reseller platforms like Vinted has “shifted the landscape”, she says. “Second-hand clothing is now filling this niche, offering higher quality vintage items at more affordable prices.”

Then there’s the Shein effect. The Chinese fast-fashion label offers a proliferation of styles at incredibly low prices that drastically undercut its rivals: you could quite easily buy an entire outfit for less than £10 (of course, this comes at a heavy price to the environment – and, allegedly, human rights). “Last year Shein saw record sales and even bought the UK online brand [and Asos competitor] Missguided,” Lewis says. They’ve benefited from “the proliferation of clothing hauls on TikTok, collaborating with influencers and celebrities, and responding quickly to fashion trends with social content”, she adds. There are even rumours that Shein has set its sights on buying Topshop.

Even though Asos is fast when it comes to chasing trends, it can’t keep up with the Shein juggernaut. But doesn’t shopping second hand and shopping at Shein sound a bit, well, contradictory? “I think the increase in popularity of both Vinted and Shein also highlights this dichotomy between young people wanting to be sustainable but also have inexpensive accessible fashion, as they’re facing a climate and cost of living crisis,” Lewis adds.

Millennials have graduated from Asos, and Gen Z are going elsewhere

Another issue that Asos is currently facing? A mountain of excess stock that has apparently proved hard to sell off: the company has previously cited unseasonable weather (think cold summers and warm winters) as a major factor. This means shoppers sometimes have to wade through older styles in order to find what they’re looking for (and often give up in the process). “For a slightly more aspirational shopper, Asos is totally overwhelming,” says Holly Beddingfield, creative strategist at Gen Z-focused media company The News Movement. “It’s hard to be inspired there. No one wants to scroll through 7,000 items to find what they need.”

Plus the near-constant barrage of backlog-clearing discounts are all well and good when you want a bargain, but they run the risk of giving the site an image problem: they scream cheap and cheerful rather than fashion-forward. “In practical terms, older and more affluent shoppers may have outgrown the Asos service, opting for slower-paced, more highly curated shopping experiences,” Beddingfield adds. “Millennials have graduated from Asos, and Gen Z are going elsewhere.”

No wonder, then, that Asos is talking up its efforts to shift this old stock and is scaling back on its new intake to avoid a repeat situation. It’s reportedly also testing a new production model, fast-tracking certain designs to ensure they’re available to shop online in a matter of weeks (a clear attempt to keep up with the likes of Shein).

Perhaps the most glaring issue, though, is the fact that Asos doesn’t really seem to know who it’s for. It’s not speedy enough to compete in the fast-fashion super leagues, but it won’t appeal to an eco-conscious consumer looking for long-term investment pieces. It lacks the design flare of more aspirational high-street favourites like Zara, while bombarding shoppers with hundreds of styles that don’t quite hit the mark. Asos is in the throes of an identity crisis – and it’ll take much more than a few discount codes to fix.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments