The extraordinary life of madcap maverick David Kirke, the world’s first bungee jumper

He was an oddball intellectual and founder of the Dangerous Sports Club, cheating death as he hurtled down Mont Blanc on a grand piano or threw himself off the Golden Gate bridge with the flimsiest of ropes (and often prodigiously inebriated). Harry Mount recalls the life of the naughty schoolboy who never grew up

In 78 years of wild, danger-addicted life, David Kirke cheated death hundreds of times.

A pioneer bungee jumper, he preferred to jump with a bottle of champagne in his hand – without checking the rope first. He leapt off Cheddar Gorge, hang-glided off Mount Kilimanjaro and Mount Olympus and hurtled down the Alps – on a grand piano or sitting at a Louis XIV dinner table.

How astonishing, then, that Kirke has just died, peacefully, in bed in his Oxford flat – not dangling at the end of a bungee rope or at the bottom of a ski slope.

He was born in 1945, the oldest of seven children of Arnold and Fraye Potter, a schoolmaster and a concert pianist. Not wanting to embarrass his parents with his antics, he changed his name to Kirke.

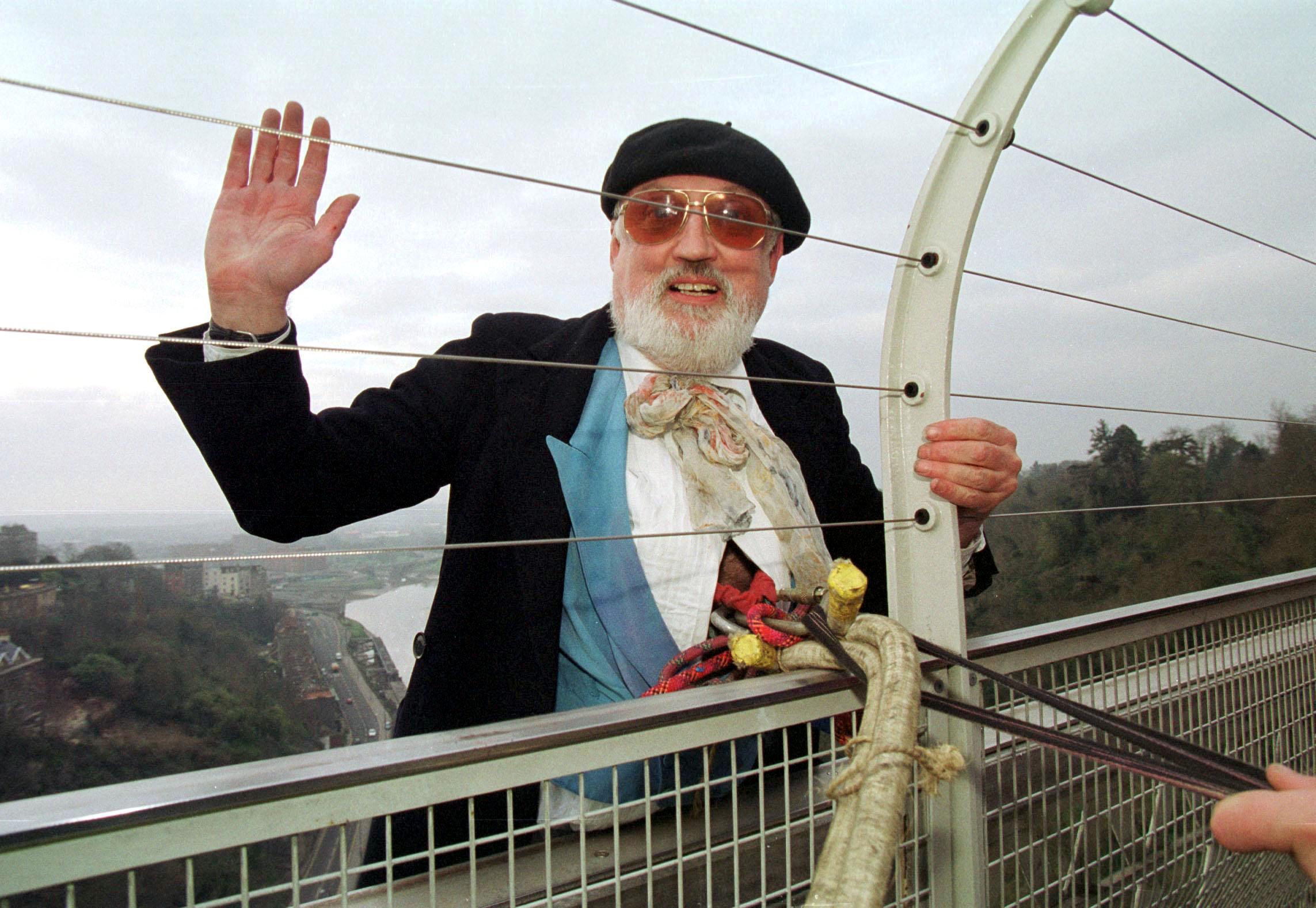

With a group of friends, he founded the Dangerous Sports Club on April Fools’ Day 1979, when they bungee-jumped off Clifton suspension bridge – David was in a top hat – after an all-night party. He hadn’t tested the rope first.

Boosted by their success, the friends pulled off bungee jumps at the Golden Gate bridge in San Francisco and the Royal Gorge Bridge in Colorado.

In 1982, the club made a film, The History of the Dangerous Sports Club. Nigella Lawson was pictured at a club tea party playing croquet from a sedan chair. Monty Python star Graham Chapman became a keen club member.

Hugo Spowers worked closely with Kirke over the club’s first ski race in St Moritz in 1983, building machines with no known relationship with snow. He remembers: “He was a fount of wildly imaginative suggestions for objects to be adapted – a stepladder, two revolving chairs, a grand piano, a rowing eight (the St Moritz authorities refused their request to go down the mountain in a double-decker bus ) – and a constant refrain that ‘remember, you can hire anything and you can insure anything’. Only he could have come up with Long Life beer as the sponsor of the event.”

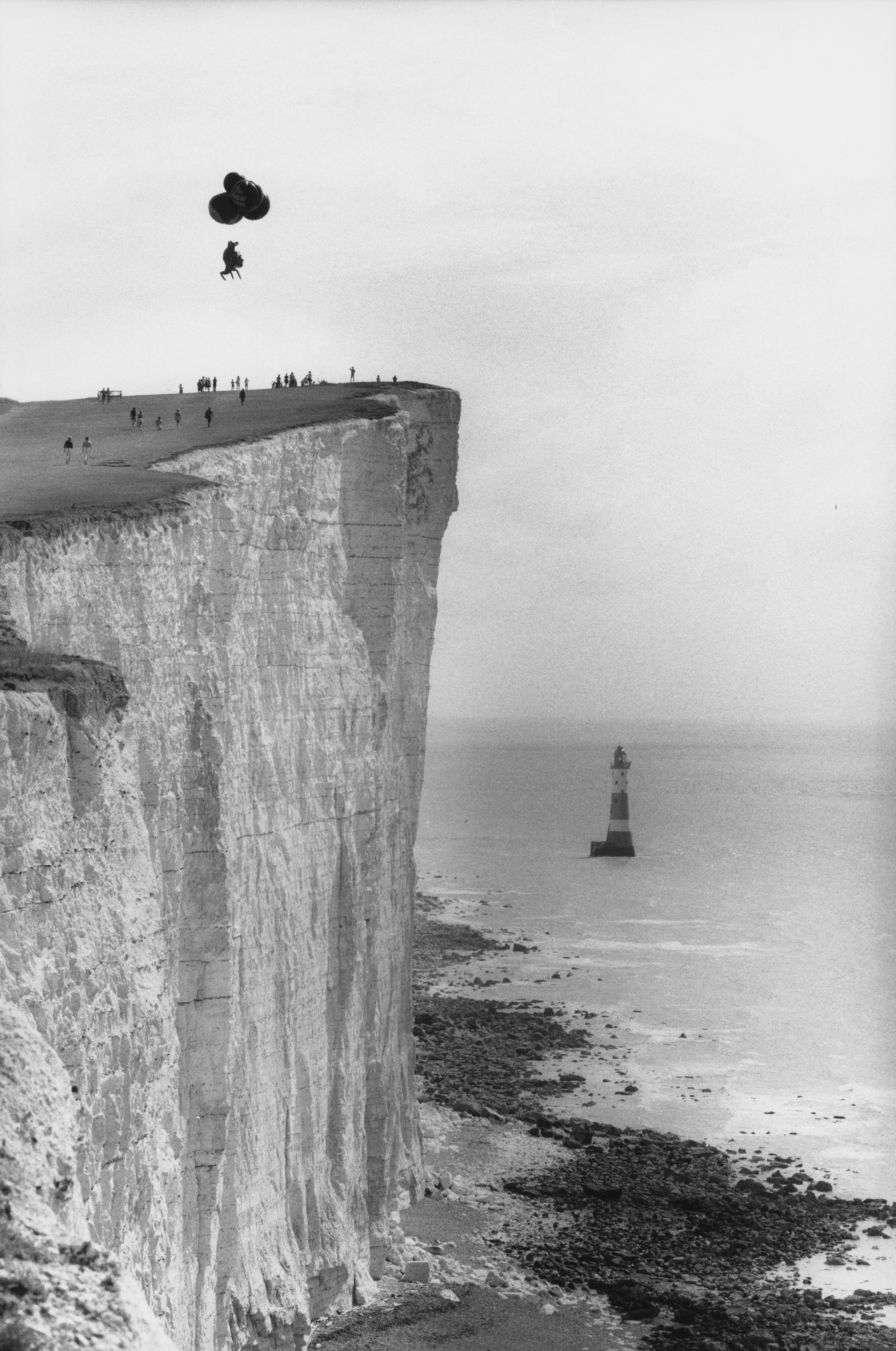

An alcoholic theme emerged in Dangerous Sports Club sponsors. In 1986, Kirke was paid by Foster’s Lager to leap off Beachy Head and fly across the Channel, tied to a kangaroo made up of helium balloons. He was prosecuted for flying without a pilot’s licence.

Midori Melon Liqueur sponsored him to be blown across the Channel to Calais in a 70ft-diameter bubble. Spowers recalls: “The passengers sat in deckchairs, with a table and beach umbrella. It failed in its first trip, through Tower Bridge. The port authorities insisted it should be towed, but this simply tore the skin and it collapsed into a sea of floating polythene.”

Edward Hulton, a founding member of the Dangerous Sports Club, built a biplane glider with Kirke in Oxford. All they had to go on was a 1909 book, How to Fly. The first flight, from White Horse Hill, Berkshire, went like a dream. But the second flight stalled and Kirke was flung out of the plane.

Hulton remembers: “The police arrived, joking, ‘back to the drawing board’. Dave was wheeled off in an ambulance, jubilant.” Hulton was astonished at Dave’s audacity, saying: “Once, when I showed I was terrified, he said, ‘you’re a member of the Dangerous Sports Club, not a Streatham hairdresser!’”

“I asked him what was the difference between an abject failure and a snivelling failure. He said, ‘the difference between you and me’. He lived a vicarious life that few of us would have dared to live.”

On the day of any dangerous event, he would be in an absolute zone of his own, argumentative, impatient and not really focused on important details like checking the harness.

On a trip to Paris, Kirke and Hulton went for drinks with Louis Greig, a friend. Afterwards, they happened upon a BMW police motorbike – which Kirke swiftly lassoed, pulling it to the ground.

Greig recalls a policeman hammering on the driver’s window, saying in French: “You can’t screw around with the French police! It’s unbelievable!” Hulton replied: “Yes, it’s a bit stupid.”

The whole party was taken to the police station. They were all set free, except for Kirke, who materialised the next morning. He had been freed, without even a fine, by a new shift of policemen who loved his story, crying, “C’est Zorro!”

The stunts never made Kirke much money. The club performed at agricultural shows across the country for a small fee. And Kirke asked photographer Dafydd Jones to split any money he got for pictures of the club.

One moneymaking scheme – to put Dangerous Sports Club labels on 1,000 bottles of wine and sell them at a mark-up – failed spectacularly. The club drank all the wine themselves.

At one point, desperate for funds, Kirke was convicted of credit card fraud. He was delighted to be sent to HM Prison Reading, where his hero, Oscar Wilde, an earlier prisoner, had written The Ballad of Reading Gaol.

Spowers recalls: “He had the loosest of grasps of those social conventions that bind us all together. This unfortunate combination led to some truly appalling behaviour, usually involving money that wasn’t actually his.

“He exercised the concept of ‘my friend will pay’ to extremes, even if he had only just met someone or, as he was so good at burning bridges, had no friends at all. But, equally, when he did have money, his attitude to it made him extremely generous while it lasted.”

But there was a bigger price to pay for his devil-may-care life. Until he died, he had back problems from being fired into the Irish Sea by a cannon – a stunt for Japanese TV. Another club member once bungee-jumped off a crane but the bungee was too long. He landed on his head – and survived.

The darkest day came in 2002 after the death of Oxford biochemistry student Kostadin Yankov, 19, when he was launched from a trebuchet and missed the safety net. The whole thing had been arranged by another institution, the Oxford Stunt Factory. Kirke wasn’t involved but two of his friends were acquitted of manslaughter.

Kirke remained undaunted, saying of the trial that it was “an extraordinary test case, about the right to experiment, at personal risk, versus social responsibility”.

Dafydd Jones, who photographed Kirke’s exploits, said: “He was a very erudite, bizarre character. He was disorganised and hopeless with money but had an incredible constitution. He got through a couple of bottles of wine a day.”

When Jones met him recently, Kirke tripped up on a tram. His shirt turned red – was it blood? Concerned onlookers calmed down when they spotted a smashed bottle of red wine in his coat pocket.

Kirke often talked to Jones about a girlfriend, who’d been run over by a bus in Oxford in the 1960s. Jones says: “It changed his attitude to life – because it could end at any time.”

“The club was about making fun of things – schoolboy humour. Any accidents were just water off a duck’s back.”

Kirke was a literary intellectual. When a journalist member of the club was up against a tight deadline, David wrote his Sunday Times piece for him. Another member, Alan Weston, worked on Ronald Reagan’s Star Wars project for NASA. Inspector Morse creator, Colin Dexter, joined the club’s Thursday pub lunches in Oxford.

The laughs were everything. On their way to a dinner party on Rockall, a tiny island off the coast of Scotland, Kirke got into a duel at a service station with Hulton. “The weapons were large, red, plastic tomatoes containing ketchup,” remembers Peter Carew, a club member.

In old age, Kirke remained an oddball. Club member Simon Keeling says: “In his later years, Dave developed some quite eccentric behaviour. He carried on his shoulder a canvas shopping bag, making him look like an old tramp. Impressions were blurred by Dave growing a considerable bushy white beard, giving him a Father Christmas appearance.

“He once took my son Archie out to lunch in Bath. Archie was amazed at how Dave ate his plate of Thai noodles – entirely with his fingers – and insisted on sweeping what was left over into a plastic container which was then transferred into Dave’s sack.

“Dave would dip into the sack, saying solemnly, ‘now, I have something for you, for future generations’, and would produce from the sack an old scrap of paper, often a newspaper cutting, and urge his companion to take it away and keep it and read it carefully.

“The last time I saw Dave, I received some scraps of paper, a paperback book, a dozen brand new, unused lead pencils, each with an eraser tip, along with a long feather.”

Why did Kirke devote his life to this madcap pursuit of danger? For art’s sake.

Hugo Spowers said: “On the day of any dangerous event, he would be in an absolute zone of his own, argumentative, impatient and not really focused on important details like checking the harness.

“But when it was time to jump, he jumped; hesitation, there was none. He was obsessive in pursuit of his life’s work, which he saw as an important field of performing art.”

Harry Mount is the author of ‘Et Tu, Brute? The Best Latin Lines Ever’, published by Bloomsbury

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments