Brain – and good manners – over brawn has helped close the gender gap

Margaret Visser on the battle of the sexes and how women – through manners and etiquette – have won that particular war

“Young ladies do not eat cheese, nor game, nor savouries, ” states a late Victorian etiquette book. The reason was almost certainly the same as that occasionally suggested for women not drinking: their breath would cease to be pleasing to men. Women still conform to expectations about eating less than men do, and preferring lighter, paler foods—chicken and lettuce, for example, over beef and potatoes.

In Japan, women were actually given smaller rice bowls and shorter, slimmer chopsticks. In the Kagoro tribe of northern Nigeria, men use spoons, but women are not allowed this privilege. Among the Pedi of South Africa, in the 1950s, women and children used the special men’s porridge dishes, but only when they were cracked and “no longer sufficiently respectable” for male use. Cooking and serving food to the men as they do, women are accustomed all over the world to eating what is left over from dinner; they are often able, of course, to look out for themselves while preparing the meal.

In Assam, where pollution rules mean that lower castes may accept food from higher castes but not the other way round, a woman eats from the same plates as her husband, after the men have finished their meal: nothing could make the pair more intimate, and nothing could more clearly demonstrate that she is lower than he.

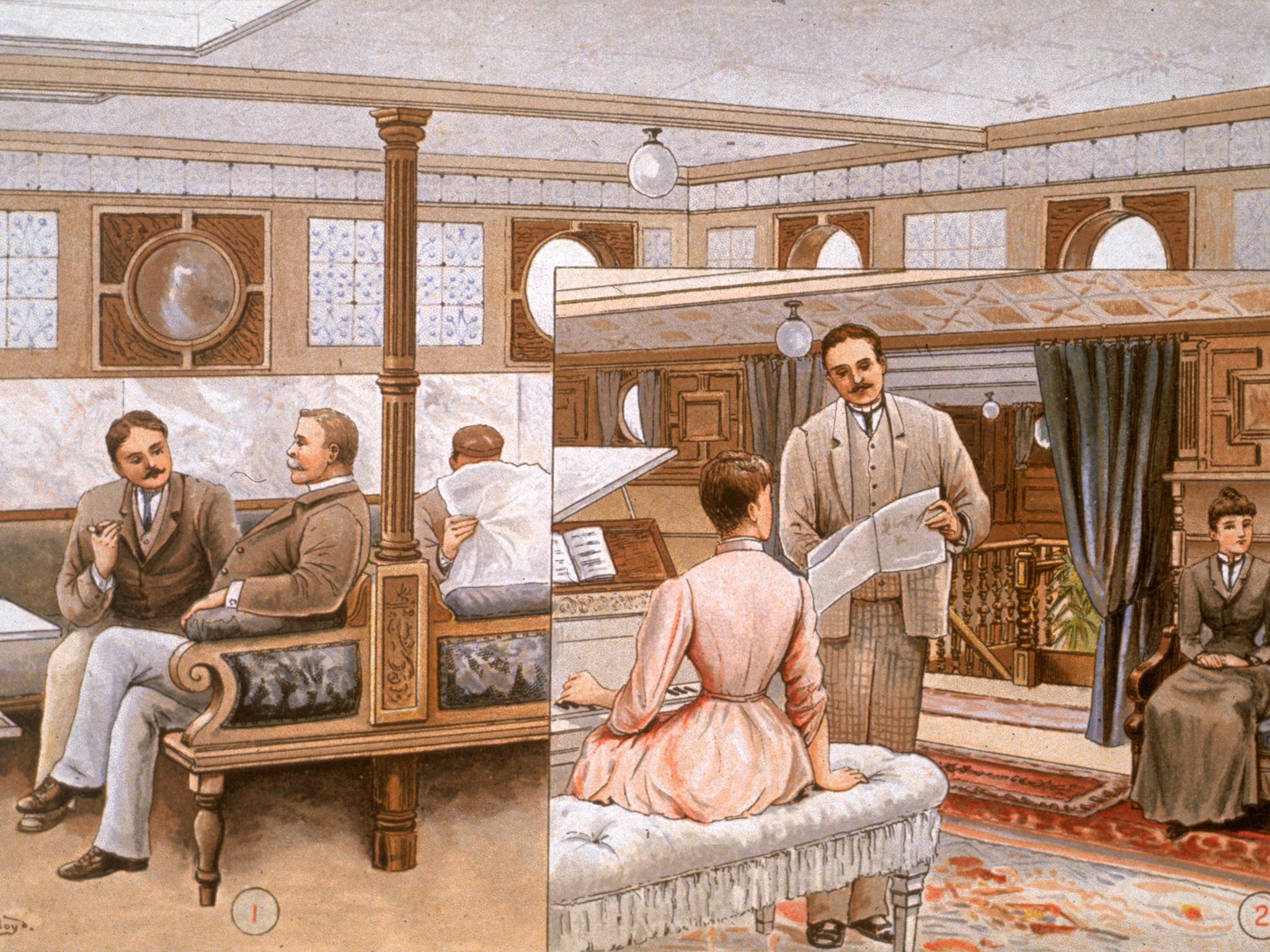

In Europe, families have often eaten all together at home, though where several families lived in one dwelling and dinners fed a lot of people, it was probably most common for the men to be fed first, served by the women. It was the nobility who took part in most of the formal banquets, and among them women were sometimes admitted, sometimes allowed on sufferance, and sometimes excluded altogether.

During the Middle Ages, women might sit in a gallery or balcony especially provided so that they could watch the men at dinner. But noblemen could at certain places and times sit each with a female partner beside him—“promiscuous seating, ” as the Victorians were to call this arrangement. Another possibility was for all the women to sit at one end of the table, apparently as meticulously ranked as were the men at their end. At very big banquets there might be ladies’ tables, apart from the men’s. We are told that Louis XIV would invite particular women whose company he fancied to join him at high table, or have the noblest and most beautiful women seated at his table for him; his wife the queen, who might be present, or obliged to preside over a separate, all-female dinner elsewhere, did not have the equivalent privilege.

From Elizabethan times women seem to have carved meat at British tables; this is a marked departure from the outlook which insisted that knives were the perquisites of males. In the early eighteenth century the hostess often did all the carving and serving of meat at table. Lady Mary Wortley Montagu as a young girl took carving lessons; on the days when she presided over her widowed father’s table, “she ate her own dinner earlier in order to perform without distraction. ” As the century progressed, men would offer to help their wives or daughters in this task. But by the end of the eighteenth century, servants increasingly carved for the diners; and with the arrival of dinner à la russe in the mid-nineteenth century, carving at formal meals was invariably done by servants, away from the dining table itself.

At family dinners, the tradition has survived in Britain of the chief male portioning out the roast before the assembled group. At the end of dinner, wrote Emily Post in 1922, the hostess, having decided that the moment has come, “looks across the table, and catching the eye of one of the ladies, slowly stands up. The one who happens to be observing also stands up, and in a moment everybody is standing. ” The choreography is strict: the gentlemen give their partners their arms and conduct them out of the dining room into the drawing room. They bow slightly, then follow the host to the smoking room for coffee, cigars, and liqueurs.

If there is no smoking room, the women leave the dining room alone. The host sits at his place at the table, and the men all move up towards his end. Where port is served, the bottle on its coaster stands before the host, the tablecloth having been removed before the ritual begins. He pours for whoever is on his right—to save this person, seated in the honourable place, from having to wait until last to be served. Then the bottle is slid reverently along the polished wooden table-top (originally so that the dregs might be disturbed as little as possible, though all good ports should be decanted before they are drunk); or it is rolled along in a wheeled silver chariot; or it is handed with special ceremonial gestures from male to male, as drinking cups were handed at ancient Greek symposia. But port is passed clockwise (to the left), not as drinks circulated in ancient Greece, to the right.

At the British Factory House dinners in Oporto, the men move into a second dining room in order to enjoy vintage port, for fear of any smell of food interfering with the drink’s aroma. The men discuss politics, and sit with whomever they like; hierarchical seating is often suspended at this time. It is even correct for a man “to talk to any other who happens to be sitting near him, whether he knows him or not, ” wrote Emily Post in 1922: the men are at last among themselves, and rules can be relaxed. The women, meanwhile, are served coffee, cigarettes, and liqueurs in the library or the drawing room. The hostess sees to it that no one is left out of the conversations which take place. The ladies would leave the men to it, and perhaps eventually have to go home alone, as drinking and roistering continued into the night. In eighteenth-century Scotland, according to Lord Cockburn’s Memorials, “saving the ladies” meant that the men would take their womenfolk home, then return to the scene of the dinner party to drink competitive healths to them. They paired off to see who could imbibe more in honour of his true love, “each combatant persisting till one of the two fell upon the floor. . . ''.

Heavy toasting died out during the nineteenth century, but a new reason for the men staying on alone came in with the advent of smoking, which at first respectable women would not dream of trying. By the time the ceremony of the ladies’ withdrawal was described by Emily Post, it had been firmly contained within constricted time limits. There had been significant changes: for example, it had previously been necessary for the women to send a servant in to call the men to them—in Thomas Love Peacock’s novel Headlong Hall (1816), “the little butler now waddled in with a summons from the ladies to tea and coffee. ”

The dinner party, with its newly necessary “promiscuous” seating (men and women alternating at the table), had been an exhausting performance; it had actually been quite difficult, because of the seating, to speak to people of the same sex as oneself. The after-dinner time among men at the table or women in the drawing room was conceived as a relief from having too strictly to “behave. ” English nineteenth-century novelists often use the separation of the sexes after dinner as a chance to further the plot by means of free conversation, and a male character’s arrival from the dining room, his choice of a female partner for conversation, became dramatic expressions of the women’s interest in him, and of his preferences.

All through history, women have been segregated from men and from public power, and “shielded” from the public view; they have been put down, put upon, and put “in their place”—a place defined by males. Yet this is not the whole story; and in the long run it may not be the most important story. For women have been an enormous civilising influence in the history of humankind. It is not only that the way women are treated in any specific society is an infallible test of the health of that society. Women have also played the role—and it has been with the connivance of men—of consciousness-raisers in the domain of manners, comfort, and consideration for others.

And the more men prized civilised manners, the more they “behaved” in the presence of women. The ideal claimed by Americans in the nineteenth century, when the custom of the ladies leaving the men after dinner was found distasteful, was in fact a sign that grown men were ready to think it normal to behave decently even when there were no women present. Women certainly felt more immediately the advantages of courtesy and accepted the ceremonial artificiality which saw them as “weaker” than men, but also “finer. ”

Women had to be bowed to, have hats lifted to them, doors opened for them, seats offered to them; they were served first at dinner. Theirs was, ritually speaking, the higher place, in spite of the underlying realities of their social and economic position. Women in “polite society” consequently became sticklers for etiquette—conservative perhaps, but also protective of the gains conquered. The etiquette manuals, many of them written by women in the nineteenth century, are filled with comments about male difficulties with correct behaviour, and bristling with advice about how men might improve themselves. They always assume that women find it far easier to manage all the skills and nuances required. And in fact it has come to pass that in many important respects women have won. Men who succeed and are admired in our culture must demonstrate that they have opted for finesse, sympathetic awareness, and self-control.

“Male” vices which men forbade in women, such as alcohol abuse and smoking, have become disreputable in men also—although many women are now claiming the “right” at last to indulge in them. Fighting, swaggering, overeating have all gone out of style; one result of the technological revolution has been to remove the requirement that “real men” should show themselves to be rough, tough, and overbearing: one does not need to be physically powerful in order to control the instruments of technology.

The gap between the sexes has closed not only because women have increasingly entered what has until now been the men’s public sphere of operations, but because men have gradually been made to feel that they should attain the level of behaviour which previously they expected only from the opposite sex. In short, they have become more like women.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies