A man out of time

As J M Barrie's ghost story Mary Rose comes to the stage, Paul Taylor explores how his arrested development added to his powers

Alfred Hitchcock had a lifelong obsession with Mary Rose, the haunting and achingly strange 1920 play by J M Barrie, and in the 1960s he commissioned a screenplay that opened it up but retained much of the original dialogue. He revealed his fixation in a book of interviews with his fellow film-maker, François Truffaut, in which he spoke piningly about Barrie's stage drama and joked that it must have been written into his contract with Universal Pictures that Mary Rose was the one movie he should not be allowed to make.

We shall see later why the piece had a powerful attraction for Hitchcock. It is enough to note here that his efforts to film this (by turns) whimsical, fey, creepy and overwhelmingly poignant work ended in failure and to register that the very infrequent revivals in the theatre – which include a 1970s staging with Mia Farrow in the title role – have met with mixed reactions, attesting to the play's capacity to arouse embarrassment and scepticism as well as to induce heartbreak of a psychologically searching kind.

But now, at London's Riverside Studios, there's a fresh account of this undervalued masterwork by DogOrange/Midnight (12am) Productions. Matthew Parker's interpretation passed the test with reviewers who saw an earlier embodiment last year at the tiny Brockley Jack. That version has been reconsidered and is presented on a much larger scale and with significant changes to production team and cast.

The elusive Mary Rose is to be played by Jessie Cave who was Lavender Brown in the early Harry Potter movies and who appeared as Thomasina, the unwitting young maths genius in a recent West End revival of Tom Stoppard's Arcadia. The forthcoming premiere of this show invites some reflections on the unjust neglect in which the bulk of its author's oeuvre now languishes.

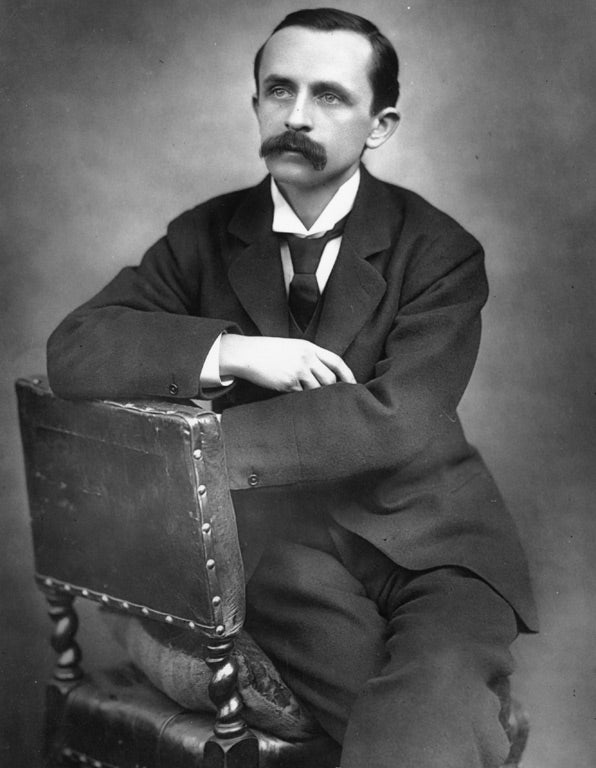

Barrie (1860-1937), the Scottish weaver's son who rose to be a baronet, was a prolific author but these days he is increasingly known only for Peter Pan, or The Boy Who Wouldn't Grow Up (1904), an adventure story that matchlessly depicts the drive towards – and the human deprivations occasioned by – the desire to remain a child forever. This is a huge pity because Barrie is one of the most distinctive voices in 20th-century drama, his work demonstrably an influence on later generations of dramatists.

Take a piece such as the yearning Dear Brutus (1917), which sets romantic hypotheticalities against war-time realities. Invoking A Midsummer Night's Dream, the location is the moonstruck garden during an Edwardian house-party where Lob, the ancient host, turns out to be Puck enjoying a freakishly extended lease of life.

At the latter's recommendation, the guests – who include an alcoholic artist married to a childless snob and a wanton womaniser and his mistreated spouse – take a walk in an enchanted wood where they get lost, encounter the alternative lives that could have been theirs, and return chastened to have discovered that they are the victims not of Fate but of their own innate propensity for choosing the wrong path.

The most Barrie-esque of these moonlit trysts, is that between the hard-drinking painter (nudgingly named Dearth) and Margaret, the daughter-that-never-was who is described in the stage directions as "a boyish figure of a girl not yet grown to womanhood... [and]... aged the moment when you like your daughter best". Dearth is ablaze with happiness and health and the long resulting duologue is a torrent of emotional over-compensation about a shared past that never happened ("I wore out the point of my little finger over that dimple") and a future that is still-born in the illusory bud.

Then, in a devastating stroke, the "reunited" pair are disturbed by an unhappy vagrant, who is Dearth's wife now only faintly recognised by him since she hails from her own alternative existence. The idyll unravels, with Margaret, like someone abandoned in a game of hide-and-seek, wailing after

"Daddikins" that, "I do not want to be a might-have-been!"

You can judge from this scene just how Barrie's work is the forerunner of J B Priestley's time-plays and Alan Ayckbourn's dramatisations of the role that chance and the crucial wrong turning, taken heedlessly play in our lives. It also exemplifies the disarmingly uncensored way in which Barrie was prepared to make theatre out of his own private hang-ups.

Mary Rose is particularly well suited to be the catalyst for a discussion of the life-beyond-Pan dimension of this author's back catalogue. It manages to have a profound and fugitive personality of its own and also has the closest affinities with the author's most famous play. The "boy who would not grow up" becomes the 18-year-old girl who remains emotionally arrested through marriage, motherhood and then, after her death, through life as a ghost in the parental home where the play begins and ends.

These are the two stage works most conditioned by the trauma that shaped Barrie's attitude to life: the death in a skating accident two days before his 14th birthday of his brother Michael. Barrie was six and, in struggling to replace this favourite in his mother's affections, he effectively stopped the clock on key features of his own psychological and sexual life (his marriage to the actress Mary Ansell remained unconsummated).

Yet he continued to develop imaginatively with the result that his peculiar predicament gives his art acute purchase on such visceral subjects as the penalties of willed and unwilled immaturity, the agony of loss, and the painful lure of speculative what-might-have-beens.

"You know how just a touch of frost can stop the growth of a plant yet leave it blooming," asks her mother as she muses about Mary Rose's permanently tomboy nature. The touch of frost in this case is Mary Rose's capacity for instinctive surrender to the spirits who tempt her to opt out of time on a kind of existential sabbatical and then return to a world that has cruelly changed in her absence with no immediate knowledge of what has passed.

She first demonstrated this talent for hearkening to "the call" when she was 11 years old, going unaccountably Awol for 20 days during a family holiday on a Hebridean island that is shunned by the superstitious locals.

The appeal of the play for Hitchcock will have become clear. The film-maker had a compulsive taste for unattainable blondes and Mary Rose, notwithstanding matrimony and motherhood (it's easier to think of her playing hide-and-seek with her boyish hubby than having sex with him) is, from one perspective, the ultimate in essential unattainability. She's a Hitchcock Blonde with an unconscious "Peter Pan" complex and an intermittent troubled sense that something is missing in her.

As this revival looks set to prove, Barrie's art is often at its deepest when it leaves an audience unable to decideif the play is aware of how extensive an emotional striptease its author is performing.

'Mary Rose', Riverside Studios, London W6 (020 8237 1111) to 28 April

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies