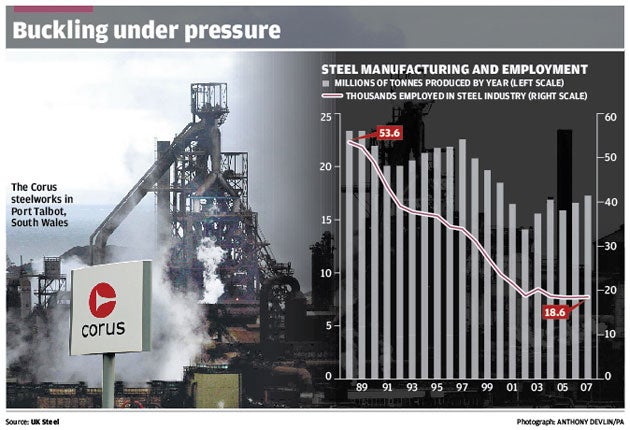

The Big Question: As Corus cuts jobs, what is the future for steel production in Britain?

Your support helps us to tell the story

This election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

Why are we asking this now?

Because Corus, the Anglo-Dutch company that dominates the UK steel industry, announced yesterday that it is to lay off 3,500 staff, some 2,000 of them in the UK. Corus's problems are not a surprise. In an attempt to balance supply with falling demand, it turned off three of its blast furnaces last year in order cut production by 30 per cent by March. Late last year the company approached the Dutch government to ask for subsidies for a reduction in staff working hours, equivalent to a cut in 1,100 full-time jobs. The company has approached Peter Mandelson, the Business Secretary, with a similar proposal for its UK operations, but with no response so far.

How important a company is Corus?

It is not only the second biggest producer in Europe, but it dominates the UK industry. The group, which was once the state-owned behemoth British Steel, represents around four-fifths of the UK sector and of its total of 42,000 staff, 24,000 are employed in the UK. Although there are some smaller steel-making companies, none come close to rivalling Corus's scale. The company has three major British plants. The biggest, at Port Talbot in south Wales, produces 4.5 million tonnes of sheet metal every year. Scunthorpe works at a capacity of around 4.2 million tonnes. Teeside produces around 3 million tonnes annually, the majority of which are sold as unfinished products in Europe. Corus also has one "mini-mill", which makes around one million tonnes of special steels from scrap. Added to that are six non-production facilities – such as rolling and coating plants – and a major distribution network.

Are these cuts just about jobs?

No. Although there are no plans to shut down any of the company's three major British facilities at the moment, Corus is selling off its aluminium smelters in Germany and Holland, as well as pushing ahead with the sale of its Teeside Cast Products operation. It is also mothballing the Llanwern hot strip mill, restructuring its engineering steels division, streamlining its distribution business and conducting a company-wide efficiency review aimed at reducing Head Office costs by 20 per cent. Corus is adamant that at least some of the measures are part of long-term, strategic changes and simply brought forward because of the exigencies of the current economic climate.

What is steel and how is it made?

There are two different ways to make it. One simply involves melting down and re-modelling scrap. The other heats iron ore and coke in a blast furnace to make "hot metal", essentially liquid iron, which is then refined in the steel melt shop, in combination with a small amount of scrap, to produce a liquid steel which can then be cast into crude steel. Crude is used to produce "flat" products – the sheeting used mainly to build cars and white goods – and "long" products like bars and mesh that are used in the construction industry.

Are the steel industry's problems inevitable given economic conditions?

Yes. Demand is collapsing as the global recession takes the wind out of both the motor and construction industries. The credit crunch and ensuing recession are wreaking havoc in the motor and building industries in both the UK and Europe, which are Corus's main markets.

Total car sales in the UK were down by 21 per cent in December alone compared with the previous year, and a recent survey of 1,000 of the country's leading house-builders found that almost half are facing financial problems as wary consumers and restricted access to credit take their toll.

Is Corus alone in its difficulties?

No, the problems are worldwide. Experts at Steel Business Briefing estimate that the UK demand collapsed by as much as 40 per cent at the end of last year. Production is also sliding. According to the World Steel Association, global production dropped by 25 per cent in December alone, falling to 84 million tonnes from 112 million tonnes in 2007. In the UK the figures were even worse, down to 580 million tonnes in December 2008, from more than 1.1 billion the year before. Prices tell the tale. Until 2004 a tonne traded between $200 and $400. By the start of last year it was $600, rising to an $1,270 in June. But as economic growth started to slow, most particularly in China, demand dipped, middle-men started to run down their inventories, and the price plunged. Yesterday, one metric tonne was trading at just $305.

Why such volatility?

The real culprit is China. When prices for steel started to rise in 2004, it was because China's vast construction programmes could not source anywhere near enough of either the finished product or its constituent ingredients from its domestic industry. To meet such voracious demand, steel production has ballooned – from the 600 million tonnes produced globally in 1970 to a record 1.3 billion tonnes last year. But as China scaled up its domestic industry, it turned very quickly from being a net importer to a net exporter. In 2000, China produced just 129 million tonnes of steel, by last year that was 500 million, a massive 40 per cent of the global total. As industrialisation slowed last Autumn, and demand for commodities dipped, it sent shockwaves through industries around the world and sent prices into freefall.

What is the history of the steel industry?

As the modern Chinese example illustrates, steel production is the engine of industrialisation. The area around Ironbridge, in Shropshire, is billed as the "birthplace of the Industrial Revolution" because it is where Abraham Darby perfected his technique of smelting iron with coke – a process central to the cheap production of steel. But the industry's real heyday was after the Second World War.

With developed economies across the world looking to rebuild their infrastructures, steel production boomed for three decades. But the oil shocks of the 1970s, coinciding with slowing growth, signalled the start of a long decline. State-owned British Steel was loss-making by the middle of the decade and over the following 10 years changed the face of the industrial landscape as it scaled back production and took out thousands of jobs. The company was privatised in 1988, merged with the Dutch producer to form Corus in 1999, and taken over by Tata Steel in March 2007 for £6.7bn.

Where does the industry go from here?

Apologists maintain that, notwithstanding the current issues, the fundamentals of the industry remain sound. As four billion people across the world strive for the standard of living available in the West, the scale of industrialisation dwarves the surge after the Second World War which produced the last boom for the steel sector. But there is a major cloud on the optimists' horizon.

At the moment China cannot hope to compete in European markets. It has neither the capability to make steel at the quality demanded by European customers, or the ability to offer services like just-in-time delivery. But as production ramps up, China turns it attention to exports, and costs in Europe continue to rise, Corus may yet come under serious threat.

So does the UK steel industry have a future?

Yes

*Corus largely serves the UK market where demand will return as the recession ends

*Freight costs make open international competition too expensive to be a threat to UK production

*Quality of both steel and services cannot easily be produced any cheaper elsewhere

No

*China's industry is continuing to grow at an exponential rate and will threaten to take over

*Long-term, high-cost European producers will struggle to compete with lower cost rivals

*If the recession is long enough and dark enough, Corus's Indian owner may lose patience

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments