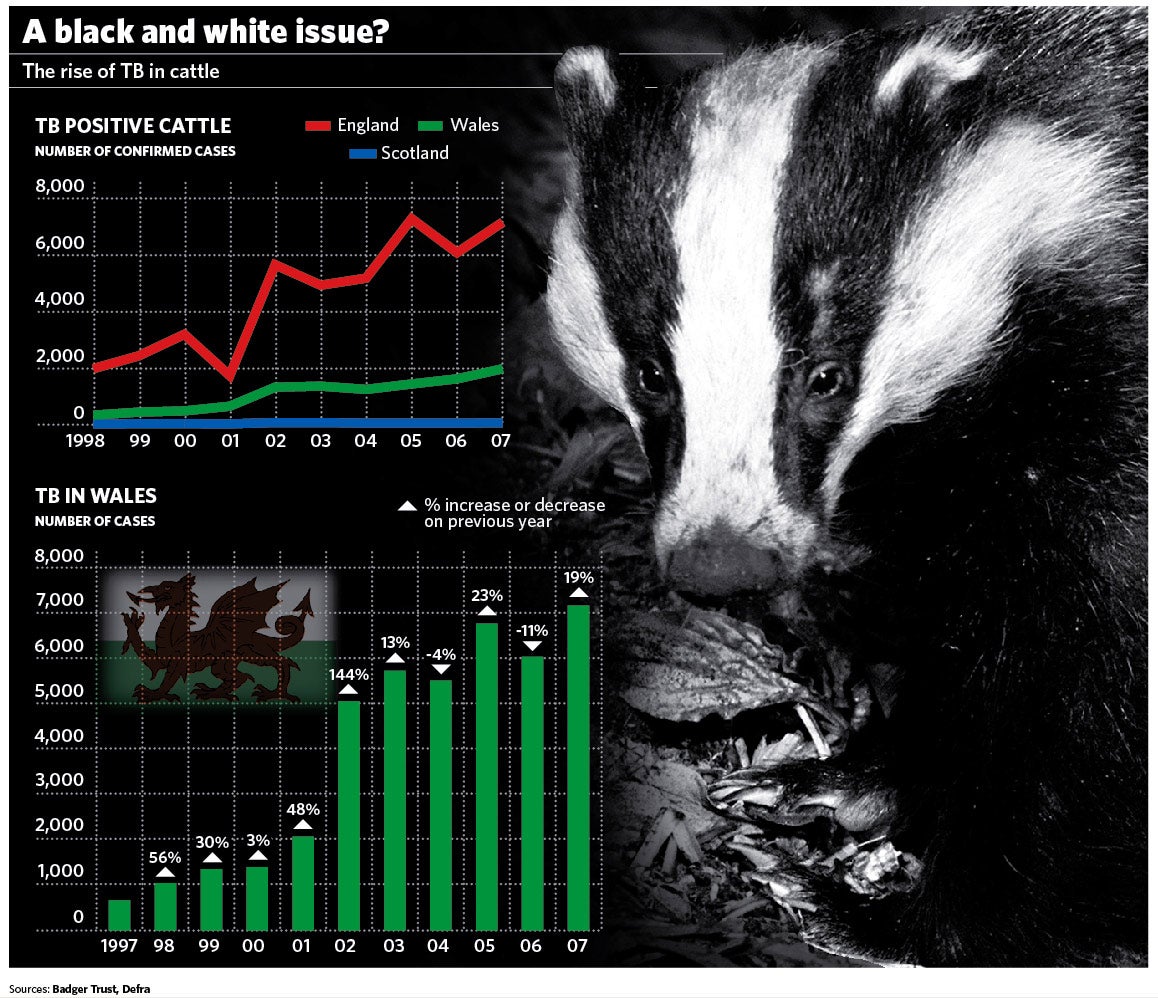

The Big Question: Should badgers be culled to check the spread of bovine tuberculosis in cattle?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Why are we asking this now?

Because yesterday the Welsh Assembly Government said it would carry out a trial cull in Wales, in a "bovine TB hotspot", to help combat the spread of the disease in the principality. Announcing her decision to Assembly Members in Cardiff Bay, the Rural Affairs Minister, Elin Jones, said "This is a difficult decision to take and it has not been taken lightly. I am very aware of the strong views on this issue."

What are the strong views?

Livestock farmers all over Britain, who are faced with a steadily rising incidence of TB in their herds, strongly believe that increasingly-numerous wild badgers, which carry the disease, are largely responsible for spreading it to their cattle. They are ever more insistent that the spread will not be halted unless the animals are substantially culled in infected areas. Animal welfare groups are adamantly opposed to any cull, saying that it would be both cruel and unjustified, and public opinion seems to support this view strongly. Most people appear to have an image in their minds of Badger in Kenneth Grahame's The Wind in The Willows, as one of the most benevolent and kindly gentlemen in the countryside.

What do scientists say?

Confusingly, serious scientific opinion supports both positions, and last year saw a quite remarkable and uninhibited clash between the two sides of the argument. It began in June with the final report of a 10-year official investigation into whether culling was the right policy to pursue.

What investigation was that?

The Independent Scientific Group on Cattle TB, or ISG, was set up following a 1997 report from a senior zoologist, Sir John Krebs (now Lord Krebs) of Oxford University, one of Britain's leading animal behaviour experts. Krebs felt that the link between badgers and TB in cattle was clearly established. He said: "The sum of evidence strongly supports the view that, in Britain, badgers are a significant source of infection in cattle. Most of this evidence is indirect, consisting of correlations, rather than demonstrations of cause and effect; but, in total, the available evidence, including the effects of completely removing badgers from certain areas, is compelling." However, he said, it was not known how effective different strategies for killing badgers – partial removal, total removal – might be in reducing bovine TB infection in any given area, and whether they would be cost-effective (for they would certainly be expensive). To explore this, the Randomised Badger Culling Trial (RBCT) was set up, costing £34m, lasting a decade, and taking the lives of about 12,000 badgers in different parts of Britain.

And what did it conclude?

That culling wasn't the answer. The chairman of the ISG, Professor John Bourne, Professor of Animal Health at the University of Bristol, eventually told ministers that "badger culling cannot meaningfully contribute to the control of cattle TB in Britain." He and his colleagues took this view largely because of an unusual and unexpected finding of the inquiry – that killing the animals on a large scale would, counter-intuitively, tend to increase rather than diminish the incidence of the disease. That was because individual badgers missed in a cull tend to wander about the countryside after their social group has been broken up, spreading the TB bacterium as they go.

So the argument was settled?

By no means. The conclusions of Professor Bourne and his colleagues were rubbished – and for once, that's not too strong a word – by the most influential scientific voice in Britain, Sir David King, who until January this year was the Government's long-serving Chief Scientific Adviser. Sir David assessed the ISG's conclusions with his own group of experts, and wrote a paper for the Department of Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra), urging that a cull be carried out. "Strong action needs to be taken now to reverse the upward trend of this important disease," he wrote, saying that the ISG's view was "unsound" – a devastating criticism in Whitehall-speak. He concluded: "In our view, a programme for the removal of badgers could make a significant contribution to the control of cattle TB in those areas of England where there is a high and persistent incidence [of the disease], provided removal takes place alongside an effective programme of cattle controls."

What was the result of that?

In the first place, an almighty scientific spat. They don't come more high-profile than Sir David – this is the man, remember, who made world headlines in criticising the US administration of George W Bush for its alleged lack of concern about global warming, and in declaring that climate change was a "more serious event than the threat of terrorism" – and his views, made public last October, were given enormous publicity. However, the members of the ISG hit back hard, aggressively reasserting their own position. Read the King report and the ISG response (you can find them on the Defra website) and you will be gripped by the spectacle of serious scientists tearing strips off each other while trying to remain polite. But in policy terms, what the King intervention did was reopen the debate, and give hope to the cattle farmers who were desperate for badger culling to be the way forward.

So where does it go from here?

The Government has to make a ministerial decision on which view to accept, and which way to go. In Wales (as agriculture is a devolved responsibility) the decision was made yesterday, on a trial basis, to go ahead with culling. The Welsh chief vet, Dr Christianne Glossop, said that the present policy of testing cattle and removal of reactors – animals that react to the test – while the movement of the rest of the herd is then restricted, was not working. "TB in cattle in Wales is out of control," she said. In England, the decision rests with the Environment Secretary, Hilary Benn, who in February was heckled at the conference of the National Farmers' Union, whose members accused him of ducking the issue. Mr Benn said he would decide after the publication of a Parliamentary Select Committee report on the problem.

When is he likely to decide?

Mr Benn appears to be in no hurry to reach a conclusion. But then – with farmers ready to lambast you if you go one way, and animal welfare activists and much of the public ready to lay into you if you go the other – would you be?

Should a badger cull take place in England to follow that announced yesterday for Wales?

Yes...

* It is established that badgers carry bovine TB and can give it to cattle

* Present control methods are not checking the increase in the disease

* The Government's Chief Scientific Advisor last year recommended a cull as the way forward

No...

* The scientists who carried out a ten-year trail say it will only make the position worse

* It will involve killing thousands of animals

* It will be very unpopular with the public

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments