Machines imitate life: The insect that goes through the gears just like a car

Discovery dispels notion that gears are a human invention – evolution got there first

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A set of mechanical gears that work just like those seen in moving instruments and engines has been discovered in a small garden insect which uses them to kick its hind legs at exactly the same time.

It is the first time that scientists have shown the existence of a gearing mechanism in the natural world. It was thought that the idea was purely an invention of the human mind.

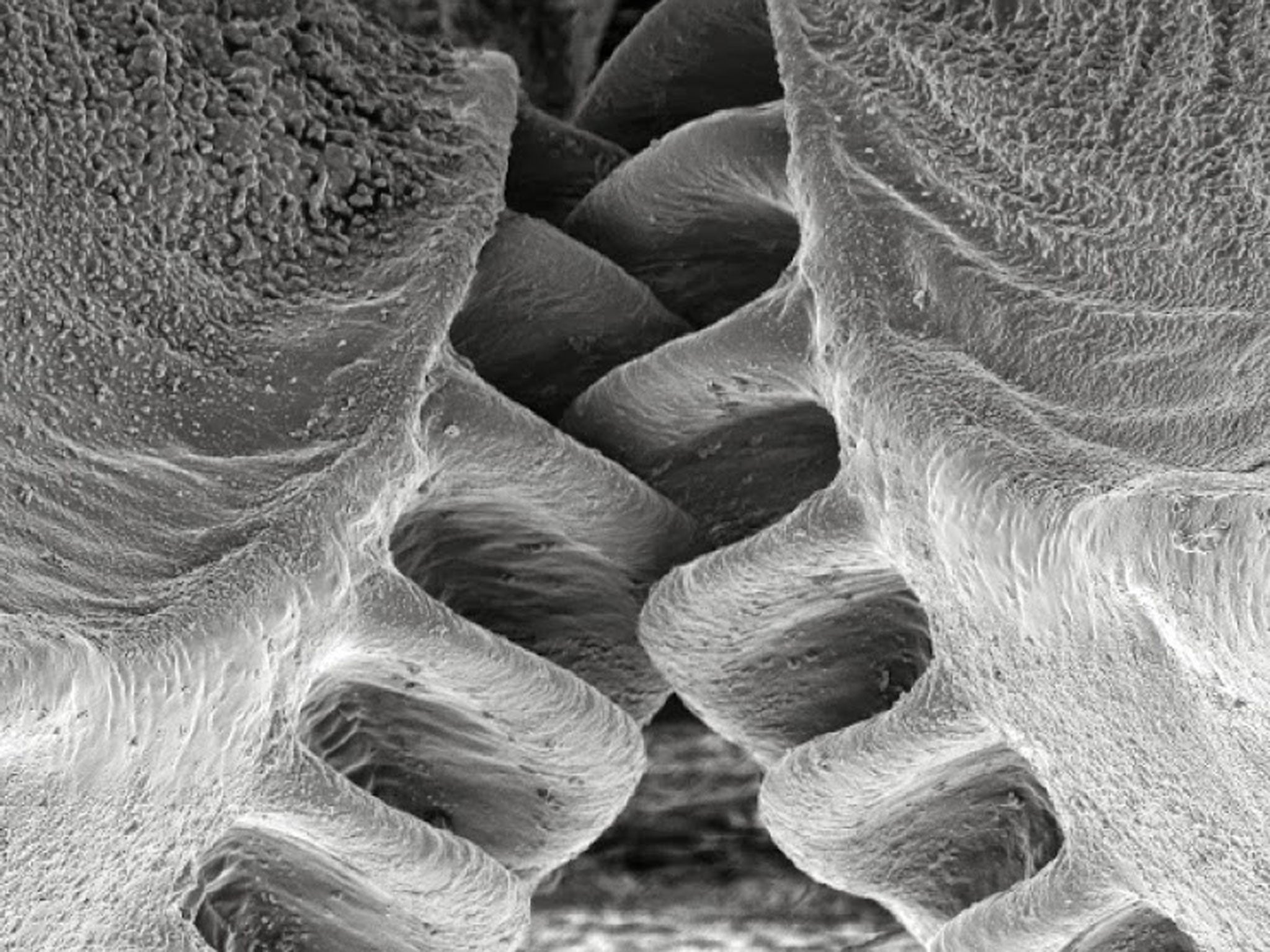

The insect, called the Issus leafhopper, has a set of curved, cog-like strips of opposing “teeth” which intermesh with one another precisely when the young leafhopper uses its hind legs to jump into the air, the scientists said.

"We usually think of gears as something that we see in human designed machinery, but we've found that that is only because we didn't look hard enough," said Gregory Sutton of the University of Bristol, a co-author of the study published in the journal Science.

"These gears are not designed; they are evolved - representing high speed and precision machinery evolved for synchronisation in the animal world,” Dr Sutton said.

Each tooth in the gears has a rounded corner at the point when it connects to the gear strip which is an identical feature of man-made gear and is designed to absorb the shock during movement so that the teeth do not shear off, the scientists said.

The 'gears' in the Issus leafhopper

The scientists combined anatomical analysis with high-speed video to capture the precise movements of the gears, which resemble those seen in bicycles or a car’s gear box.

The gear teeth on the opposing hind-legs lock together to ensure almost complete synchronicity in leg movement - the legs always move within 30 millionths of a second of one another, said Professor Malcolm Burrows of Cambridge University, who led the study.

"This precise synchronisation would be impossible to achieve through a nervous system, as neural impulses would take far too long for the extraordinarily tight coordination required," Professor Burrows said.

"By developing mechanical gears, the Issus can just send nerve signals to its muscles to produce roughly the same amount of force - then if one leg starts to propel the jump the gears will interlock, creating absolute synchronicity,” he said.

"In Issus, the skeleton is used to solve a complex problem that the brain and nervous system can't. This emphasises the importance of considering the properties of the skeleton in how movement is produced."

The gears are only seen in juvenile Issus and are lost when the insect matures into its adult form. Scientists believe this is because gears cannot be repaired if broken except during the “moults” of the juvenile stages when the entire skeleton is replaced.

Each gear strip in the juvenile Issus was around 400 micrometres long and had between 10 to 12 teeth, with both sides of the gear in each leg containing the same number – giving a gearing ratio of 1:1.

While there are examples of apparently ornamental cogs in the animal kingdom - such as on the shell of the cog wheel turtle or the back of the wheel bug - gears with a functional role either remain elusive or have been rendered defunct by evolution.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments