How India and Pakistan are competing over the mighty Indus river

A 1960 treaty on sharing waters in the Indus Basin is proving inadequate for the problems the two rival powers face today, such as the side-effects of dam-building and global warming

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

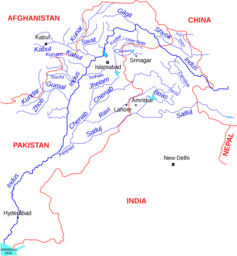

Your support makes all the difference.The Indus is one of Asia’s mightiest rivers. From its source in the northwestern foothills of the Himalayas, it flows through the Indian state of Jammu & Kashmir and along the length of Pakistan to the Arabian Sea. The river and its five tributaries together make up the Indus Basin, which spans four countries and supports 215 million people.

Yet fast-growing populations and increasing demand for hydropower and irrigation in each country means the Indus is coming under intense pressure.

India and Pakistan, the two main countries in the basin, divided up rights to the various tributaries under the Indus Waters Treaty of 1960. The treaty has survived various wars and other hostilities between the two countries, and as such it is largely considered a success. Today, however, the treaty is increasingly faced with challenges it wasn’t designed to deal with.

India recently fast-tracked approval for several major dams along the Chenab, a 560-mile-long tributary of the Indus that was originally allotted to Pakistan under the agreement. This follows several other contentious dams already being built on shared rivers including Kishanganga, on the Jhelum River, which was also allotted to Pakistan.

Under the treaty India does indeed have a right to “limited hydropower generation” upstream on the western tributaries allotted to Pakistan, including the Chenab and the Jhelum. However, many in Pakistan worry that even though these proposed dams may individually abide by the technical letter of the treaty, their effects will add up downstream.

Because the Indus Waters Treaty does not provide a definitive solution, the two countries have frequently sought time-consuming and expensive international arbitration. From time to time, Pakistan has raised concerns and asked for intervention on the storage capacity of Indian dams planned on shared rivers allotted to Pakistan under the IWT.

Basin countries have also not been forthcoming in sharing data and announcing planned hydropower projects ahead of time.

Environmental degradation

Other challenges are completely outside the scope of the treaty. First, global warming will raise the sea level and make Himalayan glaciers, the ultimate source of the Indus, melt ever faster. Dangerous flooding is expected to become more frequent and more severe.

Climate change is also expected to affect monsoon patterns in South Asia, and could result in less rainfall for India and Pakistan. This could be disastrous as summer monsoon rainfall provides 90 per cent of India’s total water supply.

The basin’s watershed area has suffered tremendous environmental degradation and massive deforestation on both sides of Kashmir, leading to a decrease in the annual water yield.

The IWT does not rule on such issues. Currently, there is no institutional framework or legal instrument for addressing the effects of climate change on water availability in the Indus Basin.

India and Pakistan also share an important aquifer – essentially a vast pool of underground water covering an area of 16.2 million hectares across both countries. This “groundwater” helps support the huge population in the Indus region, accounting for 48 per cent of all water withdrawals in the basin.

But far more water is being taken out each year than is replenished by rain and other recharge sources. One recent study said the Indus was the most overstressed major aquifer in the world, thanks to population growth and development pressures in both countries.

Despite this, the 1960 treaty also does not have any clause to deal with transboundary aquifers, and there are no agreed rules for the allocation and management of shared groundwater.

A whole new conflict

As with most of Asia’s great rivers, the Indus ultimately begins on the Tibetan plateau, in Chinese territory. India currently has no treaty with upstream China on their shared rivers. How that relationship develops will determine India’s future water availability and in turn how India behaves towards downstream Pakistan.

Similarly, Pakistan and Afghanistan have no water sharing agreement for the Kabul River, an important tributary of the Indus which supplies up to 17 per cent of Pakistan’s total water. As Afghanistan strives to develop its hydropower, with the help of Indian finance, this could instigate a whole new conflict on the Indus itself.

The authors of the Indus Waters Treaty can’t be blamed for not anticipating climate change, huge population growth or modern hydropower issues. After all it was drawn up in the 1950s. The IWT does have a clause for “future cooperation” which allows the two countries to expand the treaty to address recent challenges like climate-induced water variability or groundwater sharing. But the historical trust deficit between the two countries has prevented meaningful dialogue.

But it is clear that these new challenges require all countries in the basin to acknowledge their dependence on each other and discuss joint solutions. Expanding the water sharing agreement to include Afghanistan and China would be a start. Including these two countries, especially China, would also help to address the power asymmetry between India and Pakistan and pave the way for a more holistic sharing agreement over the Indus waters.

Fazilda Nabeel is a doctoral researcher at the Centre for Water Informatics and Technology at the University of Sussex. This article was originally published on The Conversation.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments