Gulf of Mexico 'dead zone' is already a disaster – but it could get worse

Oxygen-free areas will continue to grow until we stop pumping excess nutrients into the oceans

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

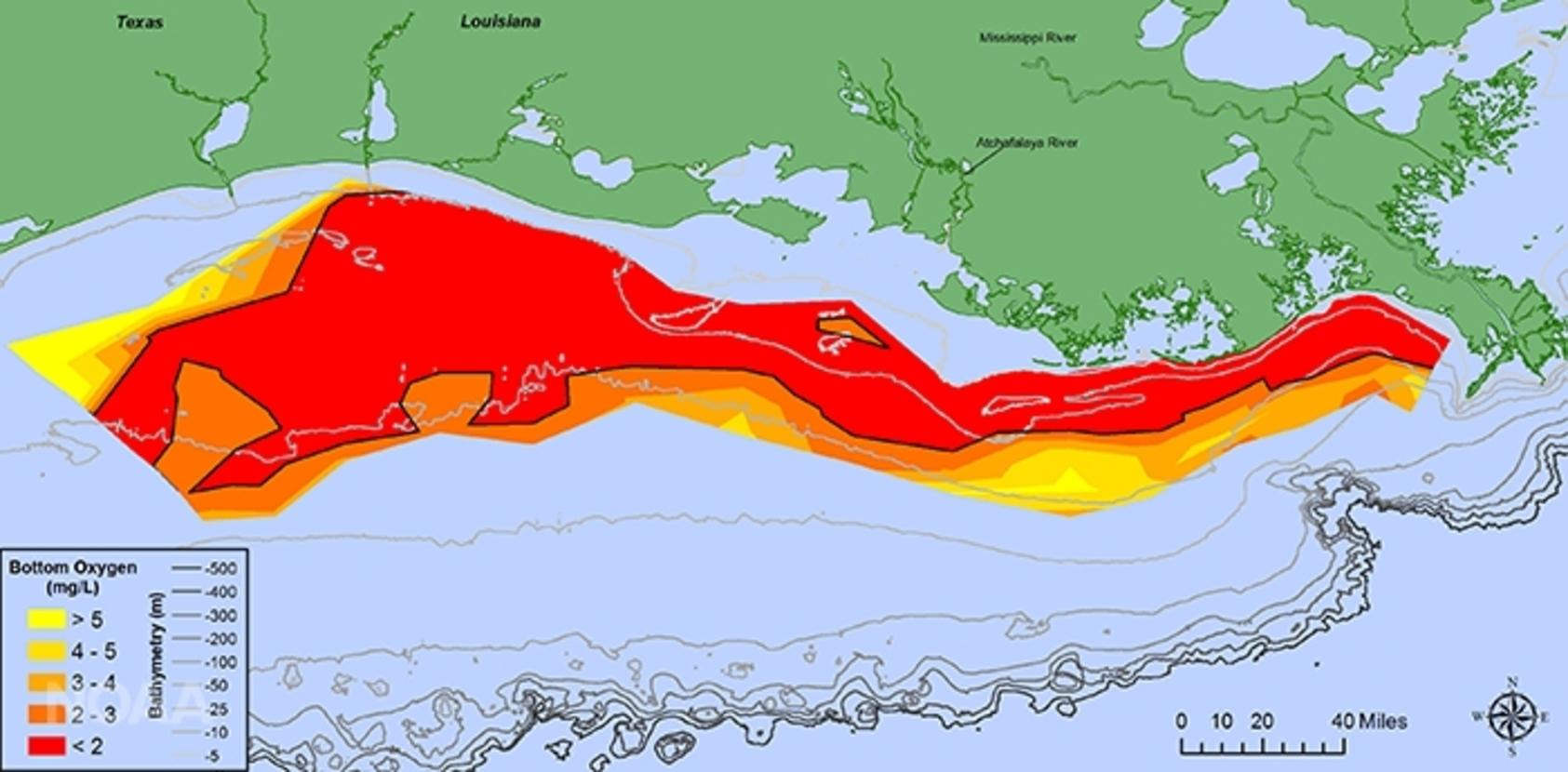

Your support makes all the difference.Each summer, a large part of the Gulf of Mexico “dies”. This year, the Gulf’s “dead zone” is the largest on record, stretching from the mouth of the Mississippi, along the coast of Louisiana to waters off Texas, hundreds of miles away. Around 8,776 square miles of ocean, an area the size of New Jersey or Wales, is almost lifeless.

John Muir, the famed naturalist and early conservation campaigner, once said that “when we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the Universe”. His point was that everything in nature is connected, and that no part of our ecosystem exists entirely independently from any other.

It is perhaps no surprise then that the ultimate cause of the Gulf of Mexico’s dead zone can be found many miles inland. Fertilisers used by farmers wash into the Mississippi River and eventually into the sea, where nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorus stimulate an explosion in microscopic algae, creating huge “algal blooms”. The algae then die and sink to the bottom, where they decompose. But the same bacteria that decompose the algae also use the sea’s oxygen during the process, leaving an “anoxic” ocean.

Fish and other mobile sea creatures are able to escape the suffocating dead zone. Less lucky, however, are the sponges, corals, sea squirts and other animals who live their lives fixed in one place on the sea bed. Low oxygen levels place them under great stress and we have seen huge mortalities. Such losses will of course ripple up the food web, creating a negative chain reaction of increasing mortality rates in larger and larger animals.

The “dead zone” has grown this year due to increased rainfall in America’s Midwest washing ever greater amounts of nutrients into the Mississippi, which ultimately end up in the Gulf. Not only is this a huge conservation issue – the Gulf contains key nursery habitats such as mangrove forests, sea grass beds and coral reefs that benefit adjacent fisheries – but it also has huge consequences for the local fishing economy, particularly the shrimp industry.

Steps are under way to slow down the ecological disaster. Some farmers in the Mississippi basin are using large grassy zones along waterways to soak up the agricultural fertilisers and filter out many of the nutrients before they make their way down the Mississippi to pollute the Gulf. However, it remains to be seen whether such measures are effective – and US farmers certainly need to greatly reduce the nitrogen and phosphates they use.

In the century since Muir’s death, things have sped up. A larger population demands more food which means more deforestation, more farmland and more fertiliser. The increased demand placed on our land is ultimately affecting the marine environment.

These losses are unsustainable. The marine environment is integral for all life on earth, from an ecological and economic point of view. If we keep losing ecosystem services such as coastal nursery habitats and spawning grounds at this current rate, it will not just be an area the size of a state that is a dead zone, but the whole Gulf, or even whole oceans.

Ian Hendy is a senior scientific officer at the Institute of Marine Sciences at the University of Portsmouth. This article was originally published on The Conversation (www.theconversation.com)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments