The tides are changing: Sea levels rising at faster rate than predicted, study finds

The annual rate of increase has more than doubled since 1990

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Global sea levels have risen faster than previously thought over the past century, suggesting that climate change is having a greater-than-expected impact on the rising oceans, a study has found.

A new way of estimating global sea levels since the start of the 20th Century found that the period 1900-1990 experienced a 30 per cent smaller rise than researchers had previously calculated.

This would mean that since 1990 there has been a greater-than-expected acceleration in annual sea levels, with the annual rate of increase more than doubling compared to the preceding 90 years, the scientists found.

Until the age of satellites, sea levels were calculated mostly from readings of tide gauges unevenly dotted around the coastlines of the world.

However, this non-random distribution introduced an element of bias that overestimated sea level rise up to 1990, the researchers said.

Previous estimates suggested that the global mean sea-level rise over the 20th Century was between 1.5 and 1.8mms a year.

However the new estimate, based on a revised statistical analysis of the data, suggests the annual rate was about 1.2mm between 1900 and 1990 and about 3mm per year since 1990.

“What this [study] shows is that sea-level acceleration over the past century has been greater than had been estimated by others. It’s a larger problem than we initially thought,” said Eric Morrow of Harvard University.

Previously, researchers gathered tide gauge records from around the world, averaged them together for different regions and then averaged those rates together again to create a global estimate, Dr Morrow said.

“But these simple averages aren’t representative of a true global mean value. Tide gauges are located along coasts, therefore large areas of the ocean aren’t being included in these estimates and the records that do exist commonly have large gaps,” he said.

“Part of the problem is the sparsity of these records, even along the coastlines. It wasn’t until the 1950s that there began to be more global coverage of these observations, and earlier estimates of global mean sea-level change across the 20th Century were biased by that sparsity,” he explained.

Sea levels are rising through a combination of the thermal expansion of warmer seawater, the melting of glaciers and ice sheets and the faster run-off of freshwater from the land due to human irrigation projects.

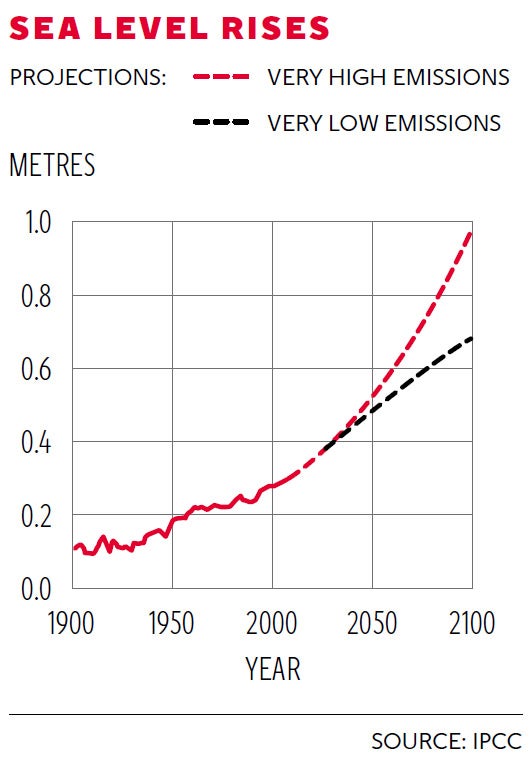

The last report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) estimated that the average global rise in sea levels could be between 52cm and 98cm by 2100 for high CO2 emissions and between 28cm and 61cm for lower emissions.

This would mean that even if the world commits to lower greenhouse gas emissions under a new climate treaty, many coastal areas will still be seriously threatened by a sea-level rise of about half a metre by the end of this century – and further inevitable rises in subsequent centuries.

“We are looking at all the available sea-level records and trying to say the Greenland has been melting at this rate, the Arctic at this rate, the Antarctic as this rate and so on,” said Carling Hay of Harvard University, the lead author of the study.

“We expected that we would estimate the individual contributions, and that their sum would get us back to the 1.5mm to 1.8mm per year that other people had predicted,” Dr Hay said.

“But the math doesn’t work that way. Unfortunately, our new lower rate of sea-level rise prior to 1990 means that the sea-level acceleration that resulted in higher rates over the last 20 years is really much larger than anyone thought,” she said.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments