Norman Hunter channeled the instincts of the terraces and spirit of an age

Not every player can produce a piece of flamboyant skill. Hunter and his fellow enforcers were the embodiment of the crowd on the pitch. They were Everymen, in a very different Britain

There was something uniquely satisfying about Norman Hunter’s footballing persona. He felt like a fictional character, created to embody ‘Dirty Leeds,’ the most brilliant, cynical side that England had produced.

Just saying the name was gratifying. Try it. Norman Hunter.

Norman provokes a mass of images – robber barons, 1066 and all that – but in a game of word association it is most obviously linked with ‘conquest.’ Norman definitely came to conquer.

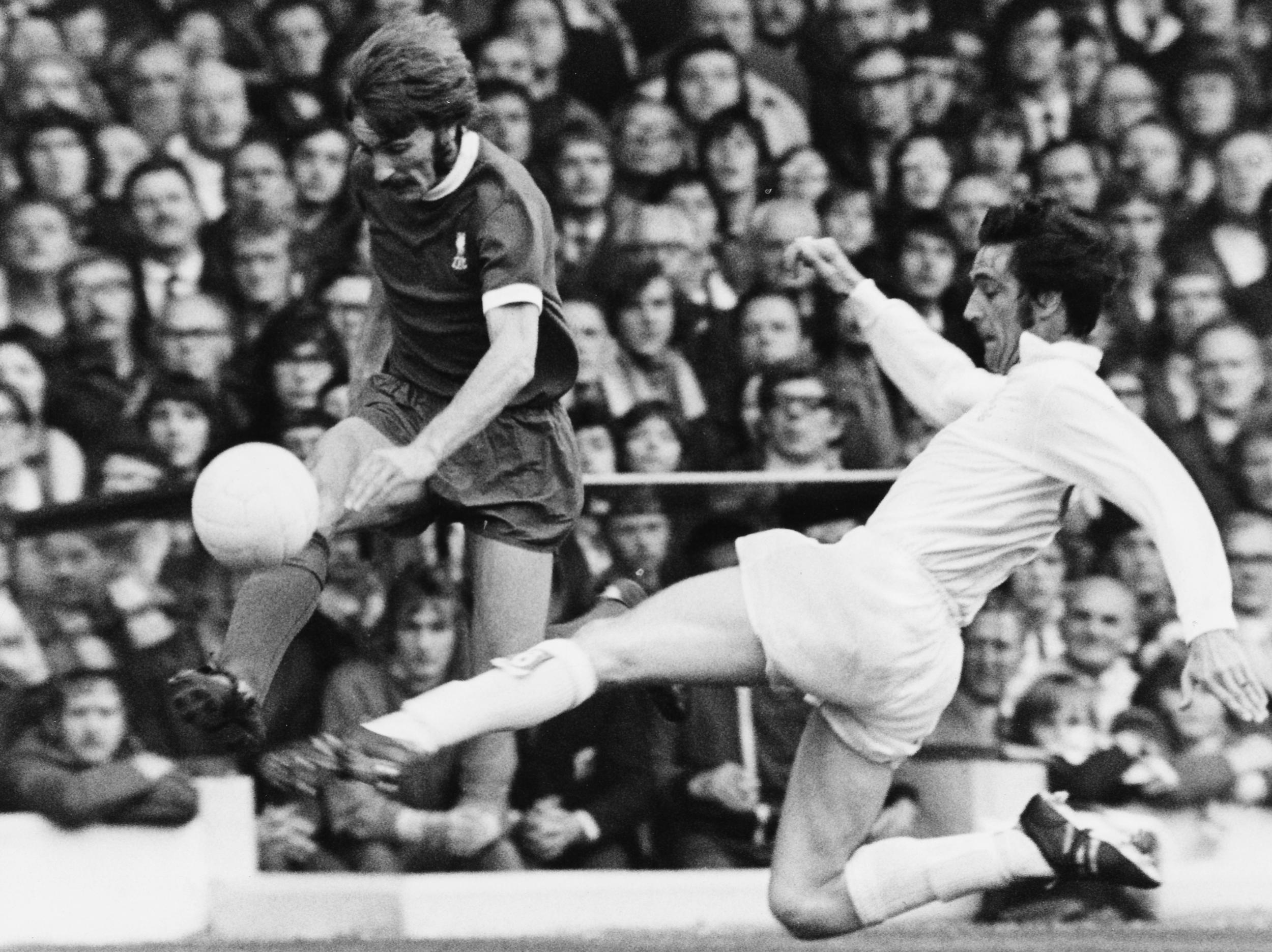

Hunter speaks for itself. The Leeds United defender pursued opponents with glee. His tackling expressed the thrill of the chase. The sport has changed and the joy of seeing an attacker mown down has been removed from the game. Rightly so. But when Hunter was in his pomp crowds flooded through the turnstiles in thrall to the idea of the tackle. They wanted physicality. Men like Hunter provided it.

Homer Simpson wanted to be Max Power; in the early 1970s young boys all over the country wanted to be Norman Hunter. We would chop at friends’ ankles during street games and call out “Hunter!” at the moment of contact. An act of skill would be accompanied by a cry of “Keegan” or “Best”; a powerful shot by a shout of “Lorimer” or “Charlton.” But Hunter was perfect for when brute force was required. He did not need a nickname like Chopper Harris. Tommy Smith sounded too ordinary. The “Norman Bites Yer Legs” banner at the 1972 FA Cup final gave Hunter a new middle name that stuck for the final decade of his career but it was unnecessary. By then he was already an iconic character to hordes of overaggressive schoolboys.

Britain was different in the 1970s. Watching football was still a cheap, working-class activity. The nation’s industrial base had not yet been eroded and labour was more manual and life more rugged. The game’s core support came from neighbourhoods where families often operated on tight budgets. In these communities status was more likely to come from toughness than wealth. Hard men were admired on and off the pitch.

Not everyone could produce a piece of flamboyant skill but tackling was another matter. Hunter and his fellow enforcers were the embodiment of the crowd on the pitch. They were Everymen, channelling the instincts of the terraces.

Except they weren’t. Hunter – like Smith and Harris – was much more skilful than most people imagined. And we had to imagine. Televised football was limited to highlights of a handful of games every week. Live action was a rarity on the small screen. To watch the full 90 minutes on a frequent basis a supporter had to go the match. Relatively few people got to see Hunter regularly and understand just how talented he was with the ball at his feet. In those circumstances myth often gained more purchase than reality.

Hunter was never the signature character of ‘Dirty Leeds.’ Neither was Jack Charlton, with his little black book of revenge, or Billy Bremner, the snarling Scottish pocket battleship.

That dubious honour should probably go to Johnny Giles, the beautifully balanced midfielder whose snideness was as legendary as his touch. Or perhaps Allan Clarke, the centre forward famed for leaving stud marks on any defender in the vicinity. Don Revie’s team earned their reputation by rotating fouls so they would avoid being cautioned and incorporating an Italianate slyness into their approach. Hunter was transparent. What you saw was what you got.

Almost. In person he was the antithesis of the brute of popular imagination. He was almost gentile. Players often confound expectations. Chopper Harris looked like a titan on the pitch for Chelsea but in civilian clothing appeared to be a mini-me version of the fearsome defender. He is shockingly short and thin for a man who exuded dominant physicality on the pitch. And nice, too.

Smith made up for both of them. He lived up to preconceptions when off duty. Hunter was the opposite.

The 76-year-old’s death after contracting Covid-19 is sad. His life ended too soon and his family and many fans will mourn his passing. It is one of too many tragedies in this dreadful period.

A generation has lost one of its icons. Hunter represented the spirit of an age. At a time when you had to earn the right to play, he was one of the taxmen, taking his cut. Sometimes literally. He was a symbol of a different Britain, one where talentless young boys would stalk their ballcarrying playmates and bring them down while calling out in ecstasy the name of their guiding star: Hunter!

In tough times being tough was a victory in itself and many of us wanted to be just like the formidable image of Norman Hunter. There was much more to the man, though. So much more.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies