The Big Question: Should we be keeping animals such as killer whales in captivity?

Why are we asking this now?

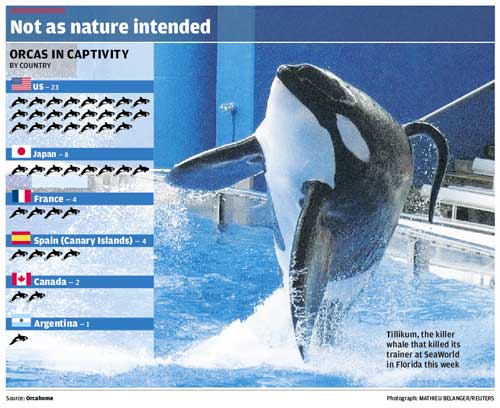

Because a female trainer, Dawn Brancheau, was killed this week by a captive killer whale which dragged her into its tank at the SeaWorld centre in Orlando, Florida.

Isn't that just a killer whale living up to its name?

Well, yes and no. The name killer whale originally came from the fact that these striking, large and fierce animals had been seen to be "killers of whales" – and they do indeed sometimes hunt other whale species in the open ocean (The name biologists increasingly prefer to use is orca, the second half of its scientific name, Orcinus orca).

Yet even though they were feared for centuries – the first known reference is in the Elder Pliny's Natural History in the 1st century AD – there is no established record of orcas killing human beings in the wild, although there have been a few cases of what seem to have been accidental or mistaken attacks.

During Captain Scott's ill-fated expedition to the South Pole a century ago, a killer whale tried to tip over an ice floe on which a photographer was standing with a dog team, but it is thought that the dogs' barking might have sounded enough like seal calls to trigger the animal's hunting instinct.A surfer was bitten in California in the 1970s and a boy who was bathing was bumped by a killer whale in Alaska several years ago, but there have been very few attacks in the wild, and none fatal. In captivity, however, it's a different story.

How so?

There have been quite a few attacks by captive killer whales on their trainers. The Whale and Dolphin Conservation Society (WDCS) says: "It happens more than you think." One source suggested yesterday that since the 1970s, killer whales in captivity have attacked 24 people around the world, and some of these encounters have been fatal.

As recently as last December, a trainer at the Loro Parque animal park on the Spanish island of Tenerife, Alexis Martinez Hernandez, was crushed to death when a stunt he was rehearsing with a 14-year-old killer whale named Keto went wrong. And Tilikum, the animal involved in this week's fatal attack, who was captured from the wild in Iceland, was, with two other orcas, involved in the death of a trainer in Canada in 1991, and then of a man who had sneaked into Florida SeaWorld in 1999 and appears to have fallen into Tilikum's pool.

So why do they attack people in captivity when they don't in the wild?

The answer seems to be captivity-related stress. It's not hard to understand. Killer whales are wild animals. They are strong. They are unpredictable. They are very intelligent, with their own complex communications system. They are very social – in the wild, they live in closely co-operating social groups with maybe 10 to 20 members.

If you take one out of the sea and stick it in a concrete swimming pool for the rest of its life, do you think that will have a benign effect on the animal's personality? What, thanks for all the fish? When you consider the thousands of miles of open ocean though which wild killer whales freely roam – they are dolphins, after all, the biggest members of the dolphin family – ending up in SeaWorld is the orca equivalent of you or me being imprisoned by a lunatic in a cupboard under the stairs.

Many zoos have now recognised that close confinement of big mammals – sticking lions and tigers in cages, and elephants in concrete houses – is entirely wrong and counter-productive. In the 1970s, London Zoo, for example, held a polar bear in a concrete pit which used to pace up and down continually all day long in what was clearly mad despair. (The pit has long since been empty).

But the people who hold the 42 orcas currently in captivity around the world have too big a financial interest in keeping them in anything larger than a bare pool in which they can perform cheesy stunts for the benefit of paying tourists. And what happens is – to use the vernacular – that it does their heads in. If you think this is just opinionating, look at the mortality figures.

What do they show?

There is an increasing amount of data on orcas in the wild, especially from western Canada, where they have been studied for decades, and it is clear that in their natural state their lifespan is something similar to that of humans. They tend to live up to 50 years, but there are cases of some of the females surviving much longer, perhaps even to 80 and beyond.

In captivity the picture is very different. The figures are known precisely. According to the WDCS, there have been 136 killer whales captured in the wild and held in captivity since the first one in 1961, of which 123 have now died, and the average survival time is four years.

It is thought that the stress of captivity lowers their resistance to disease. And it clearly also alters their behaviour, leading among other things to unpredictable aggression. (The very first one to be captured, by the way, the 1961 animal, a small female taken in Californian waters, lasted one day. She died after repeatedly swimming around her pool at high speed, ramming into the sides of the tank).

So what should happen now?

Animal welfare campaigners and many biologists think that orcas should simply not be held in captivity. They should be freed, all of them. Unfortunately, it's not a simple business – you can't just chuck them back like a fish you might have caught. You would have to transfer them to pens in the sea, for them to be rehabituated to the wild, and then there is the question of whether or not they could rejoin the family pod from which there are taken.

The experience of Keiko, the orca who starred in the three Free Willy movies, shows how difficult it is – when he eventually was freed in 2002 he was never able to find a pod and only lasted 18 months, before dying off the coast of Norway.

But even if there can only be a halfway house – returning captive orcas to sea pens where they could be cared for – it is very likely preferable to a life of balancing a ball on your nose in front of 5,000 popcorn chewers.

Is freedom for captive killer whales likely?

Well, just so you know, no fewer than 21 of the world total of 42 orcas held in captivity are kept in the three US aquaria run by SeaWorld, which was part of the "entertainment business" of the giant brewing company Anheuser Busch until it was sold for $2.7bn last October to the New York private equity business Blackstone. Big bucks, big bucks. Freedom? What do you think?

Is it right to trap such wildlife in artificial environments?

Yes...

* They can perform a useful educational function for adults and especially for children, who may become supporters of conservation.

* Captive breeding, where it is possible, may be a lifeline for species which are threatened with extinction.

* Modern methods of keeping animals – in some cases –are much better than they were a few years ago

No...

* Many big animals, orcas perhaps above all, are far too large and have too large a range in the wild to be held in narrow confinement.

* They clearly suffer from captivity-related stress which makes them susceptible to disease and shortens their lives.

* They may become aggressive and become a danger to their keepers as recent fatalities have illustrated.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies