'We now know what he was doing': Does Van Gogh's last painting shine a light on his final days?

A researcher in France has discovered what is now being accepted as the place Vincent van Gogh painted his final artwork, but what does that mean for the theories on his death? Nina Siegal writes

One hundred and thirty years ago, Vincent van Gogh awoke in his room at an inn in Auvers-sur-Oise, France, and went out, as he usually did, with a canvas to paint. That night, he returned to the inn with a fatal gunshot wound. He died two days later, on 29 July 1890.

Scholars have long speculated about the sequence of events on the day of the shooting, and now Wouter van der Veen, a researcher in France, says he has discovered a large piece of the puzzle: the precise location where Van Gogh created his final painting, Tree Roots. The finding could help to better understand how the artist spent his final day of work.

“We now know what he was doing during his last day” before he was shot, says Van der Veen, the scientific director of the Van Gogh Institute, a nonprofit established to preserve the artist’s tiny room at the Auberge Ravoux, the inn in Auvers-sur-Oise. “We know that he spent all day painting this painting,” Van der Veen notes.

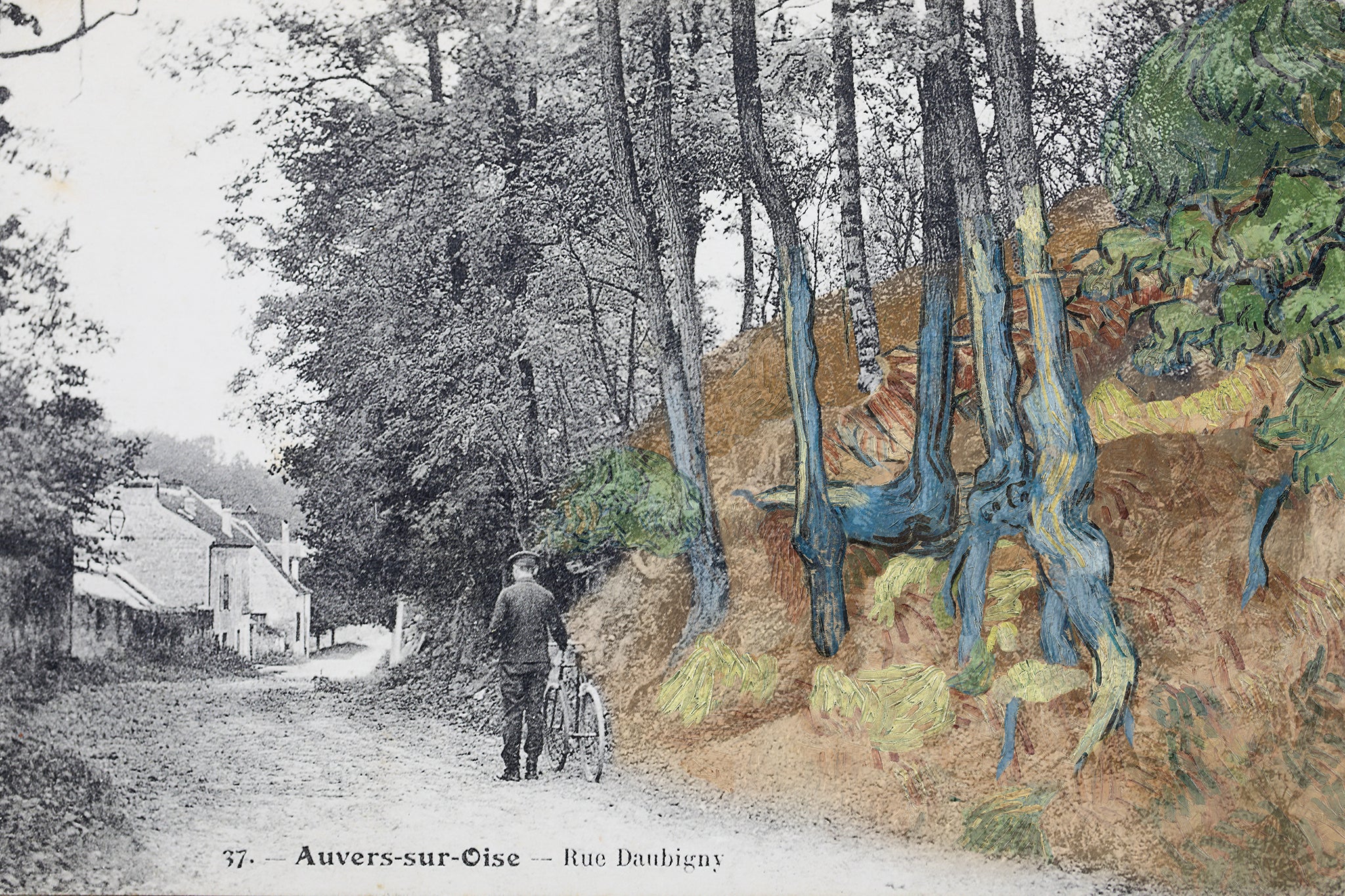

Tree Roots was painted on the Rue Daubigny, a main road through Auvers-sur-Oise, which is about 20 miles north of Paris, Van der Veen found. The tangled, gnarled tree roots and stumps can still be seen in the slope of a hill there today, just 500 feet from the Auberge Ravoux, where Van Gogh spent the last 70 days of his life.

Researchers at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam have endorsed the finding.

Louis van Tilborgh, a senior researcher at the Van Gogh Museum, says the finding is “an interpretation, but it looks like indeed it is true”.

Van der Veen says he was pointed towards the discovery while looking at images of Auvers from about 1905, which he had borrowed from Janine Demuriez, a 94-year-old Frenchwoman who has collected hundreds of historical postcards. One shows a cyclist on the Rue Daubigny, stopping next to a steep embankment, where tree roots are clearly visible.

Van der Veen says he just happened to have the postcard on his screen at home in Strasbourg, France, during lockdown when something clicked in his mind: The postcard was reminiscent of Tree Roots. He pulled up a digital version of the painting and compared them side by side.

The postcard is “not a secret hidden document that nobody can find”, Van der Veen says. “A lot of people have already seen it, and recognise the subject, the motif of tree roots. It was hidden in plain sight.”

Because he was unable to travel from Strasbourg himself, Van der Veen called Dominique-Charles Janssens, the owner of the Van Gogh Institute who was in Auvers, and asked him to take a look at the area.

“I’d say 45 to 50 per cent is still there,” Janssens says, referring to the entanglement of roots. “They cut some of the trees down, and it was covered with ivy, but we took some of that down.”

Van Gogh would have walked along the Rue Daubigny to get to the town’s church, which he painted for The Church at Auvers in June 1890, and to make his way to the sprawling wheat fields just outside of town, where he painted Wheatfield With Crows in July, Van der Veen says.

There has long been debate about which painting was Van Gogh’s last work, because he tended not to date his paintings. Many people believe it was Wheatfield With Crows, because Vincente Minnelli’s 1956 biopic Lust for Life depicts Van Gogh, played by Kirk Douglas, painting that work as he goes mad, just before killing himself.

The fact that he went out and painted all day, not just an average painting but a very important painting, indicates that he may not have been depressed

Andries Bonger, who wrote down some of the events surrounding Vincent’s death and was the brother-in-law of Theo van Gogh, Vincent’s brother, noted in a letter, “The morning before his death, he had painted a forest scene, full of sun and life.”

In 2012, the Van Gogh Museum published a paper by Van Tilborgh and Bert Maes arguing that the letter referred to Tree Roots, an unfinished painting in the museum’s collection. That claim has now largely been accepted by scholars.

Because of the way light is depicted on the roots, Van der Veen says he believes that Van Gogh was looking at his subject matter at the end of the afternoon, about 5pm or 6pm. He says he thinks this means that Van Gogh probably spent the entire day painting.

Van der Veen adds that the new evidence challenged a theory put forward in 2011 by Steven Naifeh and Gregory White Smith in their biography, Van Gogh: The Life. They argued that Van Gogh did not die by suicide, but may have gotten drunk and argued with two young boys, who then accidentally killed him, not far from the Auberge Ravoux. Van der Veen’s research on Tree Roots is published in a book in France, and will also be available in English in digital form.

“Now that we know he was painting all day, there was even less time for that to happen,” Van der Veen says.

Naifeh responds that it would be impossible to time-stamp a painting based on the angle of the light. “It’s not a photograph; it’s a painting,” he says. “Van Gogh painted somewhat abstractly, and he was always introducing a lot of painterly inventions,” he adds, so it would be hard to tell if he was painting light he saw with his own eyes or just creating it on the canvas.

Naifeh says the discovery could even support his murder theory. “The fact that he went out and painted all day, not just an average painting but a very important painting, indicates that he may not have been depressed,” he says. “It was otherwise a productive normal day, and that runs counterintuitive to the idea that he might then go and kill himself.”

Van der Veen agrees on one point. “It confirms everything that most witnesses at this time say, that his behaviour was perfectly normal in the last days,” he says. “There was no sign that he was having a crisis.”

However, Van der Veen maintains that van Gogh killed himself, which is also the official position of the Van Gogh Museum.

Van Gogh had also made a drawing of tree roots when he lived in The Hague in 1882. He described the artwork to his brother, Theo, in a letter.

He wrote that he wanted the tree to “express something of life’s struggle”, seeing it as, “Frantically and fervently rooting itself, as it were, in the earth, and yet being half torn up by the storm.”

Van der Veen says that Tree Roots expressed something similar.

“Ending his life with this painting makes so much sense,” he says. “The painting illustrates the struggle of life, and a struggle with death. That’s what he leaves behind. It is a farewell note in colours.”

© The New York Times

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies