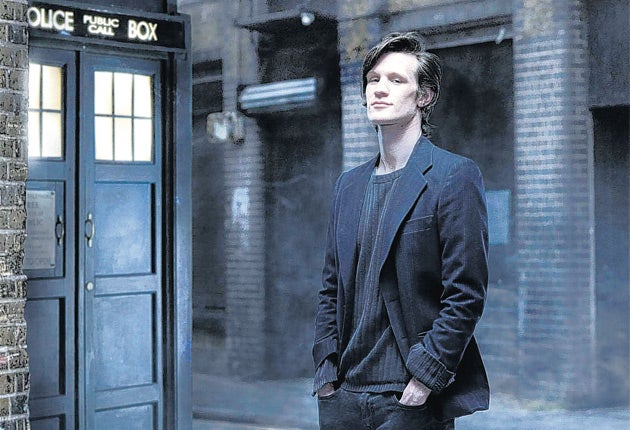

The Weekend's TV: Doctor Who, Sat, BBC1<br/>24, Sun, Sky 1<br/>An African Journey with Jonathan Dimbleby, Sun, BBC2

Time Lord's stroke of genius

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.I'm watching Doctor Who and something odd is happening. I'm feeling something – and it's not mild irritation either. Actually, I'm feeling moved, which is mildly irritating in itself in some respects, given that I've stayed bone dry through some really calculated Doctor Who tear-jerkers.

There's no gainsaying a lump in the throat, though, however treacherous you feel it to be. And this time it wasn't the Doctor who was hauling on the heartstrings but Vincent van Gogh and, behind him, Richard Curtis, writer of an episode that was at first ingenious and then decidedly poignant. The ingenuity came very early, with the vision of a familiar-looking cornfield and something big and threatening rattling the stalks as it passed. Then an explosion of crows kicked into the sky and the camera pulled back to reveal Vincent at work. What if, Curtis had asked himself, the painterly turbulence in a famous masterpiece had an extraterrestrial source? What if, peering out from the window of a Van Gogh church, there was something that wasn't meant to be there?

The Doctor spotted it – halfway through a trip to the Musée d'Orsay with Amy – and then whisked them both back to Arles in 1890, not long before Vincent finally killed himself. The set designs were supplied by Vincent van Gogh, naturally, so that the Doctor and Amy could turn a corner into the Place du Forum to discover the Café Terrace at Night, its awning glowing yellow against the dark sky. Vincent was being chucked out as they turned up and before long he and Amy were having a bit of a ginger flirtation. Back home, chez Vincent, they discovered a treasure-trove of neglected masterpieces, one of which Van Gogh casually paints over to produce an Identikit sketch of the invisible monster that's been plaguing him. Of course, the Doctor had a convenient doohickey in one of the Tardis's glove-compartments that could identify any face put before it, though it hiccuped a bit in this case. "This is the problem with the Impressionists," moaned the Doctor, "this would never happen with Gainsborough or one of those proper painters."

The invisible monster turned out to be a sort of cross between a rhino and a parrot, and was eventually employed for a bit of dying-pet pathos. I remained coldly unfeeling about its fate, but then Curtis – having danced a bit of a two-step around the difficult issue of Van Gogh's suicidal depression – gave life to a charitable fantasy that must have occurred to virtually everyone who loves his paintings. The doctor – unwilling to meddle with history to any large degree – did feel able to take Van Gogh on a temporal joyride, bringing him into 2010, so that he can see the crowds admiring his paintings and hear Bill Nighy's art expert wax lyrical about his undying genius. And in Tony Curran's tender performance of Vincent as he absorbed this fact there was something very touching – one of history's injustices corrected, if only in fantasy. It didn't do to think too hard about the implications of this invention, given what actually happened in history. Did Vincent then go back to Arles and think "I really must be going nuts if I believe in time travel. I'd better end it all"? If you didn't think too hard about it though it worked.

24, which will bear no thought at all without crumbling, finally came to an end, after Jack had personally killed 266 people (the Radio Times did the body count, not me). As far as I could see he didn't add to his tally in the very last episode of this dim-witted celebration of torture and neo-con power projection, though he did bite off someone's ear, despite having just taken a bullet through the shoulder. Bizarrely – despite his long record of evasion and lethal force – the black-ops agents sent to kill him didn't do it straightaway, as they ambushed his ambulance, but instead loaded him into a van, took him somewhere else and did a lot of talking first, thus allowing one of those miraculously efficient CTU drones to establish his whereabouts and patch through a cease-and-desist order from the president. Frankly, these guys are too stupid to live. I wanted to see Jack dead just to make absolutely sure there was no chance the series would return. Now we have to face the grim possibility that he'll make some kind of comeback.

An African Journey with Jonathan Dimbleby is intended to demonstrate that there is more to the continent than "hunger, violence or safari parks". There are, for example, bicycle-races, one of which Dimbleby watched in the Ethiopian city of Aksum, interviewing its impressively composed female winner before heading off into the countryside to see how local initiatives were working to prevent any recurrence of famine. He then visited a coffee exchange in Addis Ababa and an enterprising online shoe retailer, both of them set up by young Ethiopian women who appear to have taken a Western education back home, where their intellectual capital can be invested on behalf of fellow Ethiopians. In Kenya, across the border, Dimbleby explored how mobile phones were transforming the lives of Masai herdsmen and dropped in on an irreverent independent radio station, occasionally mentioning the problems of corruption and tribal violence that afflict Africa, but in a distinctly reluctant way. And, though the boosterism occasionally sounds a bit Pollyannaish, it is heartening – a place usually viewed as terminal up on its feet and energetic.

t.sutcliffe@independent.co.uk

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments