The Little Prince: The new film of the boy who fell to earth

Aviator and author Antoine de Saint-Exupéry never lived to see the success of his tale. With a new film version in the works, Boyd Tonkin explains why 'The Little Prince' is still charming

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It all began with the child of a Polish migrant labourer expelled from France. In 1935, Antoine de Saint-Exupéry was already a cult bestseller who had transformed his exploits as a pioneer pilot on air mail routes into books that mixed daredevil adventure with philosophical reflection. He took a trip to the Soviet Union for a newspaper assignment.

On the way to Moscow, as he wrote in 1939 at the close of his classic Wind, Sand and Stars, he shared a train from Paris with hundreds of redundant Polish workers and their families. Among them was an “adorable” boy, “a masterpiece of charm and grace” and “a kind of golden fruit”. For Saint-Exupéry, “Little princes in legends were just like him: protected, cultivated… what might he not become?” But for this little prince, who might have grown like a “new rose” into another Mozart, only the toil and pain of life in the “stamping machine” of industrial society beckoned.

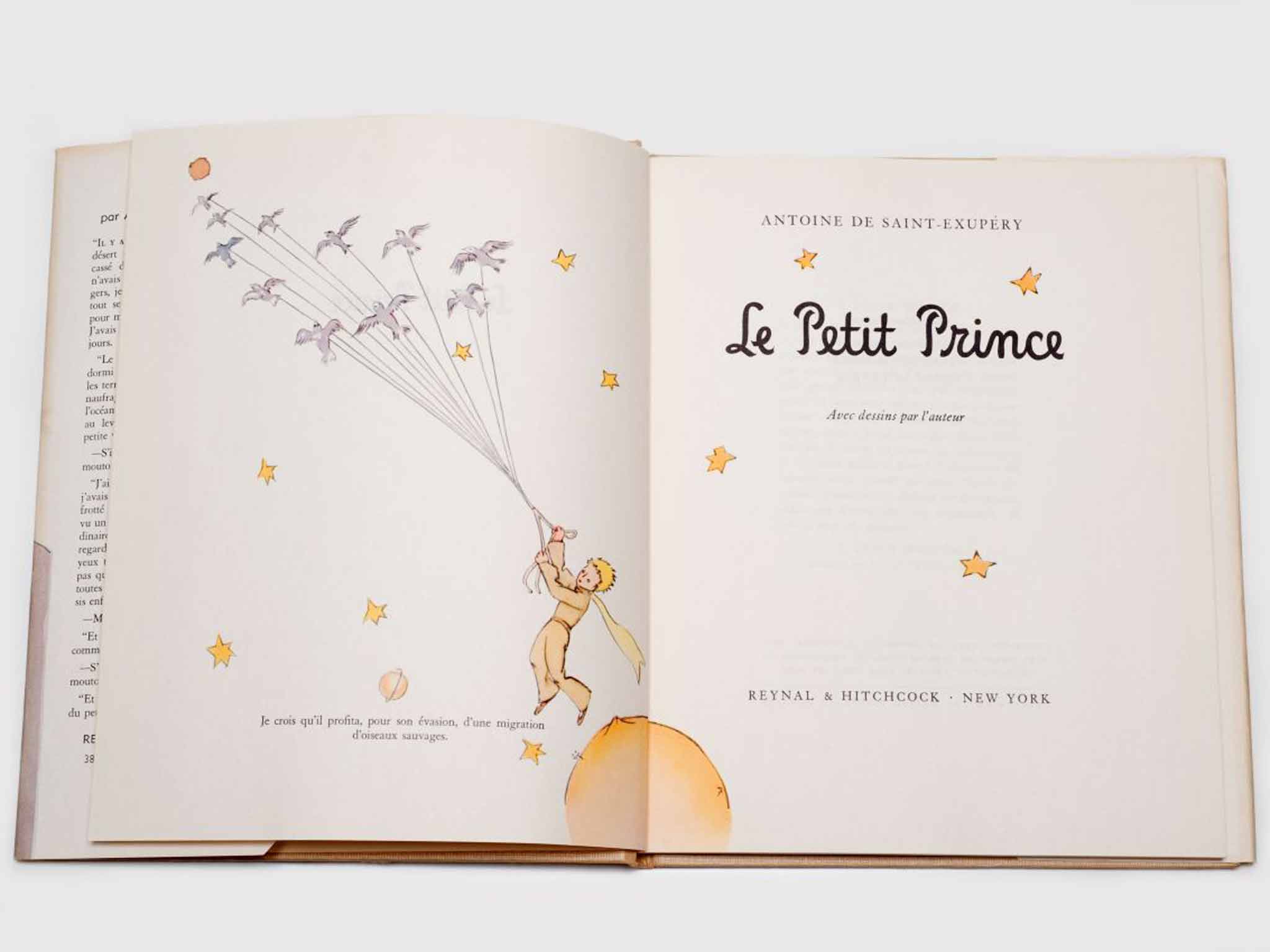

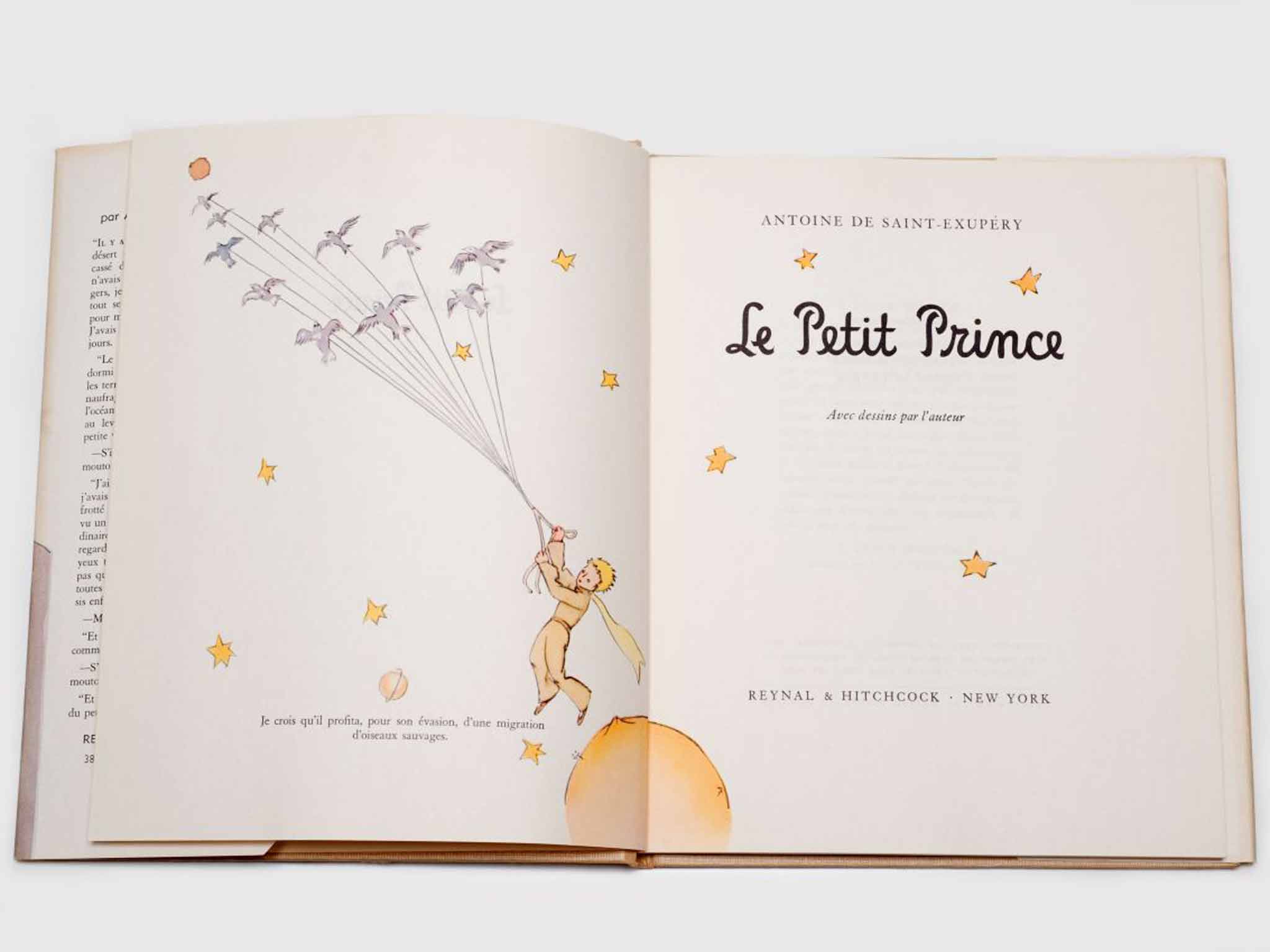

That little Polish prince, with his aura of roses and gardens, stayed with the writer. In 1942, depressed by his American exile after the fall of France, the romantic émigré needed to repair his own career in this strange land. The French wife of his New York publisher saw how well PL Travers had done with her Mary Poppins stories. Might “Saint-Ex” (as everybody called him) turn his hand to a children’s book for Reynal & Hitchcock? Saint-Ex did, working through caffeine-fuelled nights in the house he shared in Asharoken on Long Island. It was published, in both English and French, in April 1943, then in liberated France late in 1945.

Although over-age, overweight, scarred and stiff through the injuries from crash-landings, the 43-year-old author was desperate to fly again as the Allies advanced. Saint-Ex joined a Free French air force squadron based in Sardinia, then Corsica. On 31 July 1944, after his ninth reconnaissance mission, his plane disappeared into the Mediterranean near Marseille. As The Little Prince ends, the airman narrator knows that the small hero who has allowed a golden snake to bite him “did go back to his planet, because I did not find his body at daybreak”. Although the wreckage of his P-38 Lightning and even his bracelet have emerged from the sea, no one – beyond all doubt – has ever found Saint-Exupéry’s either.

Since then, The Little Prince – with its fable of an extra-terrestrial wise child from Asteroid B-612 who comforts and enlightens a crashed pilot in the desert – has grown into a planet of its own. Numbers should not really matter with a book that speaks for spirit against statistics and gently re-iterates its warning that “grown-ups love figures” and so miss the beauty of life. Still, across 250 languages or dialects and thousands of editions, the fruit of Saint-Ex’s white nights on Long Island has sold some way north of 140 million copies.

Among the ever-rising total of stage, screen, TV, graphic novel and even computer-game adaptations, an all-star animated movie will add to the figure next year. Mark Osborne’s forthcoming film – budgeted at $80m – will be voiced both in French and English, with James Franco and Marion Cotillard among its cast. Why does this gossamer tale fly so far? Frank Cottrell Boyce, children’s novelist and screenwriter, has written a Saint-Exupéry screenplay and a BBC radio documentary. He says that The Little Prince “is like one of the planets that the Prince visits – it seems small but it is a little world and it has its own gravity”. Cottrell Boyce points to the shadows of mortality that fall over the story: “It’s not surprising that a book that deals with death in a way that is both head-on and no holds barred – and yet is still charming and hopeful – really hit home in time of war.”

Dr Lisa Sainsbury, director of the National Centre for Research in Children’s Literature at Roehampton University, underlines the lightly-worn philosophical enquiry that propels the tale. For Dr Sainsbury, the story “invites the implied child reader to think philosophically and, more remarkable perhaps, rests on the conviction that childhood is a site of philosophical reflection”.

Since adults “never understand anything by themselves”, it is the child’s “propensity to ask ‘many questions’ that allows reflection on the mysteries of human being”. After all, the story asks not so much what we know as how we know, playfully dismantling the barriers to understanding put up by the “grown-ups” – who refuse, for instance, to believe in a Turkish astronomer’s discoveries until he wears Western dress.

Versions of Saint-Ex’s enigmatic parable now multiply like stars in the sky or roses in the garden. This Christmas, Britain seems to lack a Little Prince on stage. Paris has two, with Michael Lévinas’s opera due in February. The Prince gives the New Rep in Boston its current festive show. Nicholas Lloyd Webber and James Reid have written an English-language musical authorised by the Saint-Exupéry estate. Recent re-takes have ranged from Rachel Portman’s opera for the BBC to a new full-length danced version for the National Ballet of Canada. Stanley Donen’s 1974 film remains an elusive rarity. Although the 70th anniversary of the author’s death has just passed, his estate still benefits. The works of this accredited war hero have received a copyright extension for 30 more years.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

It is easy to scoff at the merchandised mutation of this delicate fable about love, commitment, imagination and individuality. Cynics might conclude that the brand has burgeoned like the Prince’s baobabs – that archetypal “bad plant” that ends as a toxic infestation which “spreads over the entire planet”. From the themed villages in both South Korea and Japan to the Espace Saint-Exupéry at the Le Bourget air museum and the branded-goods shop on Boulevard Arago in Paris, the anti-materialist wisdom of the little visitor has founded a franchised empire.

Let us not be too high-minded about the commercial fate of Saint-Ex’s angelic waif. In 1942, the pilot-philosopher was a famous but lonely author. Even before he quit Europe, he seemed – rather like his fragile Prince – a man who fell to earth. He had fled German-occupied France, taking care in his memoir Flight to Arras to antagonise the invaders by singling out a Jewish comrade – Captain Jean Israël – for special praise. Although a heroic curiosity in literary New York, he lacked a solid audience in the US. As a trailblazing pilot for the Latécoère company (later Aéropostale), this son of the impoverished aristocracy of Lyon had not only opened up dangerous routes across his beloved Sahara and then South America. Starting with Southern Mail in 1928 and the prize-winning Night Flight (1931), he had turned his ordeals into books that blend action and thought into a distinctly French mélange of metaphysical derring-do.

For all the perilous tempests over Andes and Atlas, the terrifying plunges and hair’s-breadth escapes, his ascent into speculative idealism made the intrepid pilot a fairly tough sell for mainstream America. He had fallen out as well with Charles de Gaulle and the Free French hierarchy. In short, he needed a bestseller, even if it took an improbable rivalry with Mary Poppins to open the flight-path.

Saint-Ex was a painstaking writer. As an exhibition of manuscripts at the Morgan Library in New York demonstrated earlier this year, he threw away far more pages than he kept. He also excised a despairing epilogue. Avowing that “the night is hopeless”, it fixed the fable more explicitly to wartime exile and dread.

The finished text feels both more optimistic – and more abstract. If we cherish a star or a rose that we have “tamed” until it becomes a part of us, then we may overcome loneliness and fear. No doubt the vagueness – or the ambiguity – of the message has speeded the Prince’s progress across frontiers. He has landed safely almost everywhere. Look at French cultural movements of the post-war years, and those that travel best tend to set old divisions aside in the pursuit of a reconciling humanism. For all his anti-fascism, Saint-Ex hated the internecine quarrels of the French. He proclaimed, as early as 1939, that: “We must surely seek unity.”

Posthumously, Le Petit Prince came to serve his purpose. Some sceptical readers remain unenchanted by that strategy. For Nicholas Tucker, the children’s literature expert, the story amounts to “a lot of wittering about this and that while no one actually gets up and does anything. A perfect text, therefore, for excusing what happened in France during the long periods of non-resistance to the Nazis”. For Tucker, it is “ultimately an exercise in melancholy navel-gazing just when the world needed something so much more relevant and energised”.

In spite of or because of this timeless uplift, millions still love to fly with the Prince. In 2015, Osborne’s film will recruit a new generation of devotees for a cult that began on publication in 1943. Then, the New York Herald Tribune reviewer welcomed a tale that, to be understood, “needs a heart stretched to the utmost by suffering and love”. It will “shine upon children with a sideways gleam”, and “strike them in some place that is not the mind”. Who was she? None other than the creator of a different sort of airborne saviour: PL Travers herself.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments