In The Shadow Of Kafka: David Baddiel explores The Metamorphosis for new BBC radio series

Boyd Tonkin looks at the genesis of Kafka's dark tale, and why its themes still creep and crawl around our culture

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

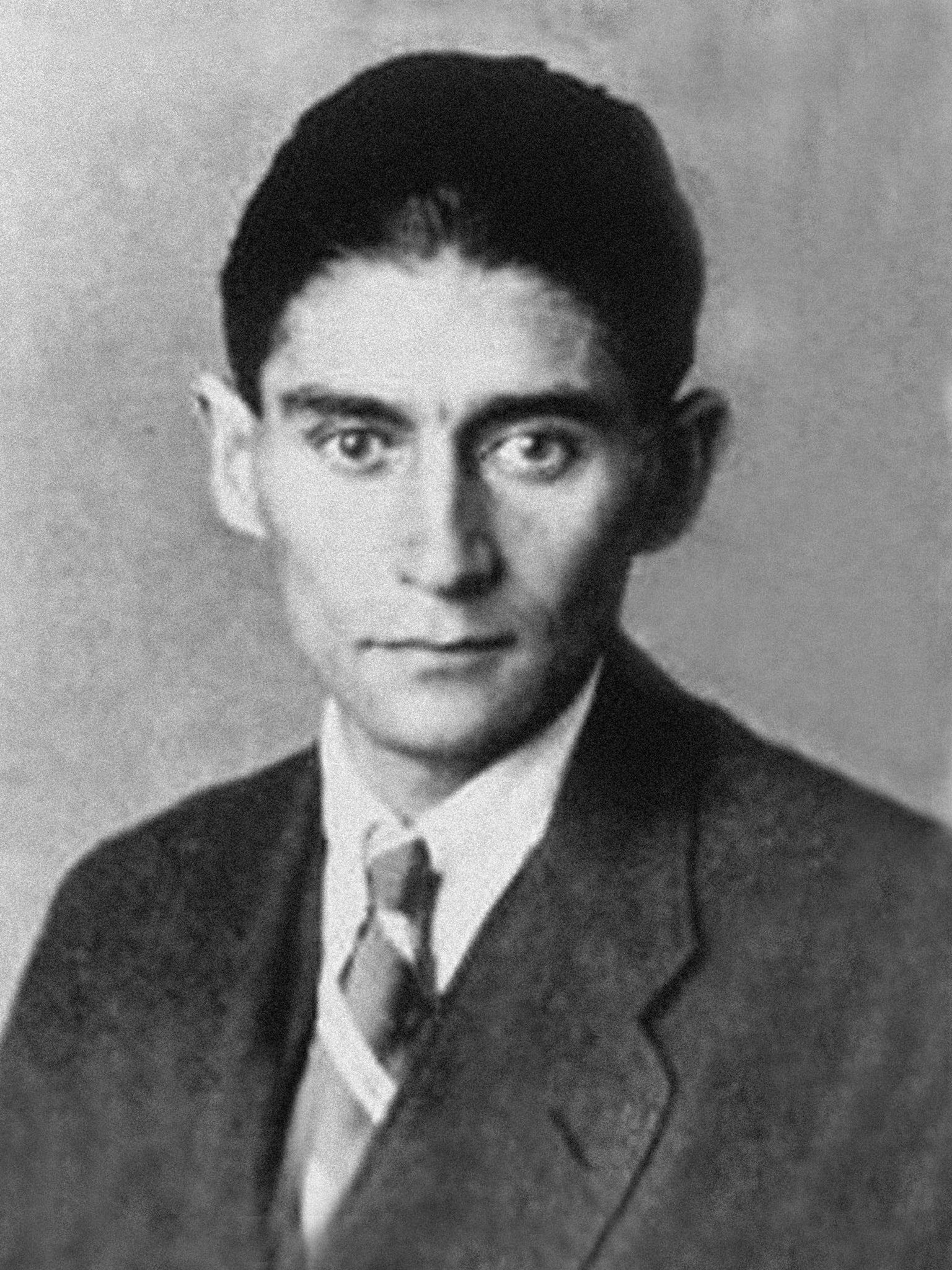

Your support makes all the difference."When Gregor Samsa awoke one morning from troubled dreams, he found himself changed into…" What, exactly? Over the century since Franz Kafka published The Metamorphosis – and the original German does have that definite article – readers have had to imagine the hideous beastie for themselves.

The story first appeared in October 1915, in a magazine called Die weissen Blätter, then in December as a slim volume from Kurt Wolff Verlag of Leipzig. But Dr Kafka, a promising young claims assessor at the Workers' Accident Insurance Institute in Prague, wrote it in late 1912; at the time, he simply told literary friends about his forthcoming "bug piece" (Wanzensache). The readers who must delve into their own many-legged mental bestiary include Kafka's swarm of English interpreters. To Willa and Edwin Muir, the Scottish bohemians who first translated Kafka into English, Gregor has turned into "a gigantic insect". For Malcolm Pasley, he was a "monstrous insect"; for Stanley Corngold, "a monstrous vermin". In a lecture, Vladimir Nabokov – lepidopterist as well as novelist – brought his expertise to bear and dubbed Gregor "a scarab beetle with wing-sheaths". Crucially, he could have flown out the window, had he wished.

To the writer and performer David Baddiel, who goes in search of the little critter at the Prague Insect Fair in a programme for the BBC radio series In the Shadow of Kafka, Gregor initially felt like "a human-sized beetle". Reading The Metamorphosis when young, he loved it even though "I did in fact have a regular nightmare about changing into an insect". When he returned to the tale for his documentary On the Entomology of Gregor Samsa, "it became clear to me this was wrong." Kafka's stricken sales rep has "numerous legs, pathetically frail". For Baddiel, "beetles only have six legs, which I don't think qualifies as numerous, and also they are fairly strong. An insect with numerous flailing frail legs would be more likely a woodlouse – which of course is not an insect but a crustacean. But then Kafka never calls Gregor an insect as such."

Kafka's original German makes Gregor an ungeheures ungeziefer, a doubly negated unspeakable unmentionable nasty creepy-crawly. In a word: "Eeurgh!" In medieval German, ungeziefer meant not merely vermin but an unclean animal unfit for sacrifice. For her excellent new rendering, the American translator, Susan Bernofsky, makes him "some sort of monstrous insect". She argues that "Kafka wanted us to see Gregor's new body and condition with the same hazy focus with which Gregor himself discovers them".

Whatever the bug may be, it's not a single species. So when, in his fine 2006 version, Michael Hofmann makes Gregor a "monstrous cockroach", he makes a strategic decision. German has perfectly good words for "cockroach": kuchenschabe or kakerlake. Baddiel thinks that cockroach sounds "just wrong". The real point of Hofmann's version may lie elsewhere. Consider the ineffable Katie Hopkins. The motor-mouthed provocateuse, you will recall, employed her column in The Sun to throw a specific insult at her fellow human beings who have sought refuge in Europe via the shores of the Mediterranean. "Make no mistake," she wrote, "these migrants are like cockroaches."

Gregor has woken as just such a subhuman pest, worthy of eradication. Yet The Metamorphosis, never forget, is also darkly funny. Baddiel's sense of its bleak humour has intensified. Now he notices, for instance, "Gregor's deadpan reaction to his transformation, the way… he worries about how he will catch the train to work and what his boss will think." Kafka and his Prague circle of chums also got the mortifying joke. Hofmann reminds us that when his stories "were read aloud, people – including Kafka, reading them – fell about laughing".

The novelist and short-story writer Clive Sinclair, who says that he owes a "particular debt" to Kafka and to Prague, regrets that "you don't see any books on Kafka and humour. Kafka and Freud, Kafka and Nietzsche, Kafka and Marx; but not Kafka and Groucho Marx, or Chaplin – and he was a fan of Chaplin". According to the logic of both farce and dream, when the sudden makeover strikes, "no one for one second questions that what has happened has happened." Sinclair notes that, in Dr K's office at the workers' insurance headquarters, "people probably came in with the most incredible stories" of life-changing injuries. He suspects that "there must also be an element of the Old Testament, and the speed of creation: like Adam waking up with one rib missing, and a hot bird beside him". In the tale's Biblical denouement, Mr Samsa Snr – that pompous old fraud – pelts his afflicted son with an apple.

Just because of this element of gross-out comedy, The Metamorphosis can then proceed to break your heart. Especially when sister Grete, who at the outset has with kindness brought her altered brother food and cleared the furniture so he can freely crawl over the walls, bursts out to their father that "we must get rid of it… You just have to put from your mind any thought that it's Gregor". The Alzheimer's-themed weepie for which Julianne Moore won an Oscar carried the title Still Alice. Perhaps the next film adaptation of Kafka's masterpiece could be "Still Gregor". After Grete's rejection, Gregor wills himself to die, having in his final moments "thought back on his family with devotion and love".

As a shape-shifting myth, the tale has undergone myriad metamorphoses of its own. In the Shadow of Kafka celebrates its author's enduring legacy. The critter, though, looms large: not only in Baddiel's Prague venture, but Hanif Kureishi's Radio 3 The Essay and, in the same strand, a meditation by Jeff Young on the story's darting, scurrying movement between languages and idioms.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Young is a prolific dramatist whose TV credits include Casualty, Holby City and EastEnders, as well as 35 radio plays. He first encountered Gregor's tale when – at his "fairly bog-standard secondary modern in Liverpool" – an art teacher read part of it to the class. "I'd never heard anything like it in my life. It was one of those defining moments." Later, in a second-hand bookshop in Liverpool, he came across an old Penguin Modern Classics copy. A lifelong passion soon took flight. "I took it to the pub, and I read it in the pub. It just blew my mind." Later, Young began to collect and compare different editions. He reports: "I'm still really fond of the Muirs' translation. The tone really is 'Kafkaesque': a very strange, slightly off-kilter version of normality."

Young reflects that, "when you come to books at different times of your life, you always discover something different". For him, the anguish of the solitary youngster barricaded in his room has faded. Now, "it's a story about fathers and sons, and families." That blustering father has himself suffered ruin and degradation: "A lot of it is about redundancy."

Sinclair agrees: "It's an economic story, rooted in the everyday." Like Young, he spots a link with another perennial family drama: "You could as an alternative title call it 'Death of a Salesman'. There is a clear connection between Gregor and [Arthur Miller's] Willy Loman, 'to whom attention must be paid'."

The Metamorphosis does indeed get everywhere. For Baddiel, it ranks as "the first modern horror piece", with "an internalised monstrosity rendered in the body of the hero". Jeff Goldblum's mutation into a hybrid arthropod, in David Cronenberg's film The Fly, is inconceivable without Kafka. On stage, Steven Berkoff's one-man show from 1969 has proved over many iterations to have legs. The Australian composer Brian Howard changed the Berkoff script into an opera. Gregor's plight jumped into yet another medium when, in 2011, choreographer Arthur Pita made him dance for a Royal Ballet production. Among film versions, Chris Swanton's 2012 movie had Maureen Lipman as Mrs Samsa, co-starring alongside Robert Pugh – and a CGI-designed bug. Less literally, Philip Glass has written five piano pieces inspired by the tale.

Kafka's disciples number countless critics as well as homage-bearing artists. In the wake of the Nazi genocide that claimed Kafka's three sisters, Elli, Valli and Ottla, one interpretation held sway. Kafka had, it was asserted, prefigured the dehumanisation of whole peoples as the Third Reich spread to engulf much of Europe. Above all, the story became a foretaste of the Holocaust. To the critic George Steiner, "from the literal nightmare of The Metamorphosis came the knowledge that ungeziefer… was to be the designation of millions of men."

Baddiel acknowledges that all these theories have their place: "It's about alienation, or isolation, or about Kafka the Jew in Prague, or whatever, and of course it is all these things." However, he found that "once you start thinking about the apparently reductive issue of what kind of creature exactly does Gregor become, then you eventually find yourself coming back to something, which is the visceral and at some level unsymbolic nature of the story. It gives you the actuality of waking up transformed into that creature". For him, "part of Kafka's genius… is that the story resists allegorical interpretation: it genuinely makes you feel what it might be like to experience this nightmare."

That nightmare begins with the anxious employee's terror at being labelled a skiver. The sickly author, remember, did a job that brought him into contact with the medics who tried to separate shirkers from deserving claimants. In the story, Gregor's company doctor recognises "only perfectly healthy but work-shy patients".

In pre-Great War Prague, as today, health meant virtue. Tough bodies bore witness to noble souls. The cultural historian Lisa Appignanesi, a specialist in the central European culture of Freud and Kafka's time, notes that "the rise of sport has begun, with the encouragement of the body beautiful – or the body healthy. There are a lot of injunctions doing the rounds". Neurasthenic illness of the sort that plagued young Franz, even prior to his diagnosis with TB in 1917, shadows this fable of a housebound and humiliated breadwinner. "Illness is terribly important at the time," Appignanesi says, citing The Magic Mountain – the novel of symbolic maladies that Thomas Mann began to write in 1912. "This is where sensitivity and genius collide with the decline of the race."

Sinclair makes the point that Kafka's self-image as a weedy nerd did not quite match the man whom others met. True, "he never trusted his own body". Yet he was tall, good-looking, charming, successful at work. "People think of Kafka as a little Jewish wimp. But he was a strapping fellow, over 6ft."

In Israel in the 1980s, Sinclair interviewed the Hebrew teacher with whom Franz – by then gravely ill in actuality – took lessons in the early 1920s. Aged 18, Puah Ben-Tovim had in 1922 travelled from Palestine to Prague to study mathematics, giving Hebrew classes to fund her stay. She described to Sinclair an eager pupil who "hunched when he walked because he was embarrassed about towering over people". Their lessons, she recalled, were punctuated by bursts of laughter.

Who or what had shrunk the soul of this debonair young executive so that he could gaze into the mirror and see a bug-like being? The usual answer runs: Dad.

Hermann Kafka had risen from dire poverty to work as a sales rep like Gregor. By the time he overawed his son, he presided over the family fancy-goods emporium in Prague. In the extraordinary Letter to My Father, written in 1919 but probably never meant to reach its target, bodily abjection fuels Franz's sense of failure. He feels more of a Lowy – his mother's better-educated family – whereas dad is a "true Kafka", in his "strength, health, appetite, loudness of voice, eloquence, self-satisfaction". Franz remembers the pair undressing together in a cubicle, "I skinny, frail, fragile, you strong, tall thickset." As Lisa Appignanesi remarks about pre-1914 Europe, "paternal authority had not quite bitten the dust then. Freud did not invent castration anxieties from nowhere."

The Metamorphosis still speaks to every cowering son – or child. Plunge into it today and the plight of "boomerang kids" priced out of independent housing may come to mind: eternal squatters, who crawl around the home and exhaust their parents' patience. Yet Kafka turns the tables on the bullying patresfamilias. Gregor has, we learn, supported the family after father's bankruptcy. When Dad works again, it's as a bank commissionaire in a comedy uniform: patriarchy as masquerade.

To the writer Deborah Levy, "my view of The Metamorphosis is that writing it was the most subversive way that Kafka could punish his tyrant father." For her, "it is a story about shame but most of all about revenge." Every reader can lend the deathless bug new legs – or wings. None will pin it down for good. While in Prague, Baddiel heard about a drama from the same period "in which capitalists were represented as dung beetles, and workers as butterflies. That's exactly what Metamorphosis isn't, and why Kafka is a genius."

'In the Shadow of Kafka' runs from 10 to 16 May. Radio 3 broadcasts Hanif Kureishi's 'Essay' on Tuesday 12 May and Jeff Young's on Friday 15 May; David Baddiel's 'The Entomology of Gregor Samsa' is on Radio 4, Saturday 9 May

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments