'The Crucible' returns: The witch hunt that implicates us all

As renowned South African playwright-director Yaël Farber revives ‘The Crucible’, she explains its enduring power

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The Crucible first came into my consciousness as a 13-year-old, living in the white suburbs of South Africa in the mid-Eighties. Apartheid was in its most violent throes. The government declared States of Emergency with regularity. The “swart gevaar” (black danger) was the mythical beast kept alive in our white enclaves by a state-engendered and community-maintained collective fear. This fear enabled a white minority to mostly continue living amid profound injustice, without engaging the capacity for outrage. More toxic even than the reorganisation of our moral code around violence and injustice was the apathy. Those who rose against the system from the safety of the protected few were rare.

How people submit to apathy in dark times was fascinating to me, even as a child. This preoccupation crystallised over the years into a world view that tends to surface in whatever I write or direct in the theatre. So too, conversely, am I drawn to expressions of the heroism of which individuals are capable. It was for these same reasons that, in the early 1950s, Arthur Miller felt the need to give voice to a largely forgotten chapter in world history: the Salem Witch Trials of 1692.

I discovered The Crucible via my older sister, who was studying the play at school. She and my late father had visited family in the United States the year before, and made a trip, text in hand, to the original village of Salem in Boston. She spoke to me of the story on her return in such vivid terms that I was drawn to seek out the text for myself. Two years later, I played Abigail in a high-school production with our brother school from down the road in a leafy suburb of Johannesburg. Outside our enclaves, the country was in yet another State of Emergency – and burning.

Reading the text in those years revealed to me the power of theatre and word, and it marked the beginning of a lifelong devotion to this craft. For the Salemites I found between those pages were painfully recognisable; here was human behaviour depicted with such delicacy and poetic accuracy that I knew I was going to spend my life engaged with such stories.

The play’s narrative is one that will repeat itself endlessly as long as we ignore the issue of collective guilt, when those in power need us simply to be amenable to doing nothing. My own most recent works, Mies Julie and Nirbhaya, ask the same questions: what do we accept as our inherited narratives? And when should we push against those narratives, defining ourselves against the given paradigm of our times?

History will show that we are no more enlightened now than the Salemites were in the late 17th century. Whether the focus is on immigrants or homosexuals, ethnicity or gender or disease, we remain largely unable to see ourselves clearly without using the “other” as our foil. The Crucible is not about malicious individuals who engineered an exceptional chapter in history when human beings lost their way. It is an articulation of the endless propensity we have for harming each other – when we believe ourselves to be righteous in so doing.

When a community abandons its ability to discern what is morally right, and when it prioritises collective obedience, it manifests what Hannah Arendt termed the “banality of evil”. But when evil becomes legitimised and integrated without resistance, how does the individual reawaken the capacity to think? When we break from the collective, making ourselves accountable only to ourselves, do we awaken, as The Crucible’s hero does, asking of himself: “What is John Proctor?” In these defining moments, when the shadow falls over our door and demands that we betray others to survive… who do we choose to be?

Being entrusted with The Crucible in order to speak of such things in today’s world is a rare privilege. Honouring the details of Salem with integrity allows us to slip through the portal of specificity and into the universal commonality of what it means to be human. That we recognise our very selves in the people of Salem is the mandate, and if our audience scorns the ignorance and cruelty of these men and women, we have failed to reach the truth of this text. For we are no wiser than they. If we were, we would return to Eden. And as Arthur Miller says: “The apple cannot be stuck back on the Tree of Knowledge; once we begin to see, we are doomed and challenged to seek the strength to see more, not less.”

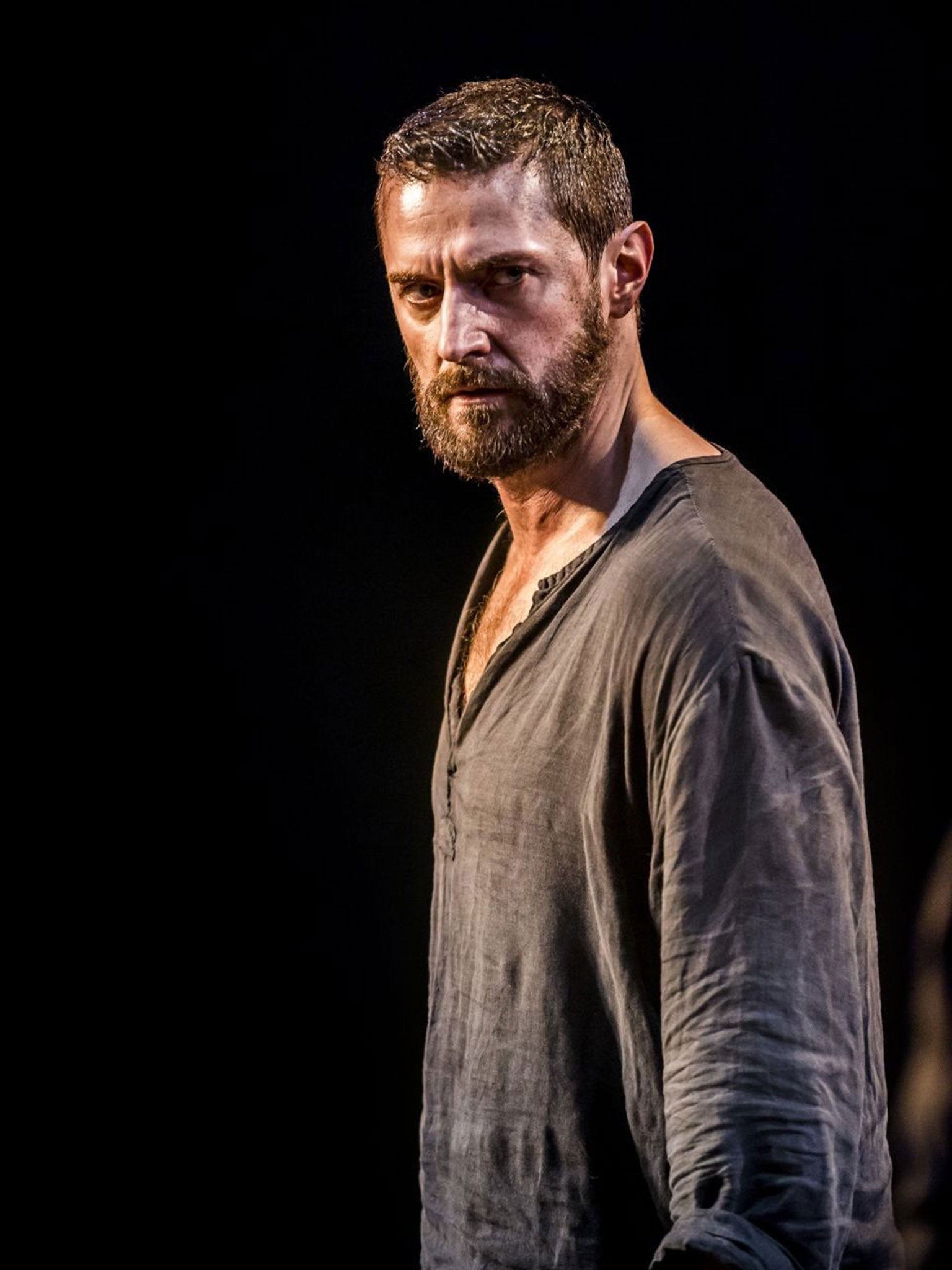

Working in the round at the Old Vic offers a unique opportunity to enter the arena – and witness the reconstitution of the individual in the form of John Proctor. With the audience seated all around us, we literally face ourselves. Like a hall of mirrors, in-the-round theatre is an evocative ritual of reckoning with the self. The beauty of the ancient arenas and circular fires around which stories were once told, is that no one is excused from the conversation. We are a part of the transmission.

And just as the story should implicate us, so too should it colonise the body. Theatre performed from the neck up – leaving out the heart, the sex and the viscera – will engage the audience only from the neck up too. A deeply physical approach to performance is fundamental to my work. I’m often asked who choreographed Mies Julie because of the intensely physical nature of the performance. To that I can only answer that, in my collaboration with the actors, in the hunt for the truth, we climb, crawl and dig our way through the text. We kneel, float and press walls to find truth.

I am fortunate to have grown up in a country that, for all its desperately deluded ideologies and brutal insistence on power for a handful of its population, taught me that to tell stories you need nothing more than an empty space, actors who are brave as samurai in matters of the spirit, some chairs perhaps – and a collective need to come and bear witness to that story each night.

‘The Crucible’ is at the Old Vic until 13 September (oldvictheatre.com)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments