The Toad Knew, Sadler’s Wells, London, review: It's admiring its own free spirit a little too much

Charlie Chaplin's grandson, James Thierrée, performs his latest rambling show with members of his own Compagnie du Hanneton, complete with acrobatics, clowning and music

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.James Thierrée’s latest show is a long 90 minutes of whimsy. A mix of illusion, acrobatics and elaborate staging, it’s highly skilled and deliberately rambling, wandering through its themes. It depends very heavily on the assumption that you will find all this charming.

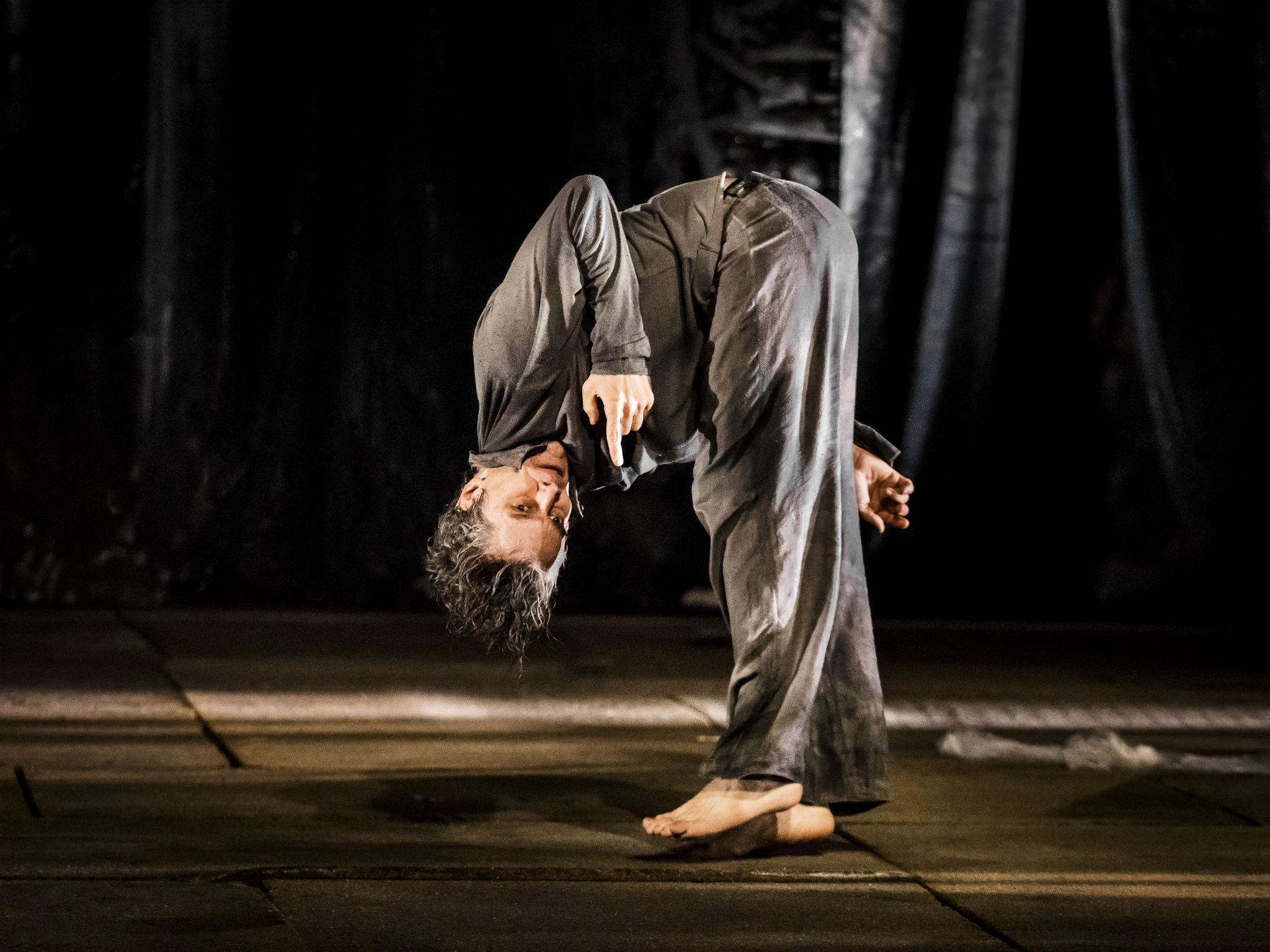

Thierrée comes from a spectacular showbiz dynasty. His grandfather was Charlie Chaplin, the playwright Eugene O’Neill was his great-grandfather; he grew up in the circus. As a performer, he’s an acrobat, clown, illusionist, mime and even violinist, joined by the members of his own Compagnie du Hanneton. His shows blend all these elements with large-scale theatre effects, aiming for dreamlike imagery.

The Toad Knew opens with a red velvet curtain that falls instead of rising. Singer Ofélie Crispin, in a matching red robe, vanishes under the bunched-up fabric – at which point her cloak, and then the curtain, move up and fly away by themselves.

Thierrée’s set is both decorative and distressed. A dilapidated piano plays itself; a tank of water suggests a paddling pool, an aquarium and a mad scientist’s laboratory. In one of the best sequences, a spiral staircase grows from the floor, its steps rising as Thierrée climbs it. The dusty junkshop look feels generic: so many surreal circus shows have used faded grandeur as an aesthetic.

Thierrée himself is in charge, though the space and his five colleagues often get away from him. With a shock of grey curls, he poses like a brooding Romantic, striking attitudes as he plays the violin. Hervé Lassïnce is ready to tidy the instrument away, except that Thierrée’s solo never quite ends. Each apparently final note leads into another, and another, until he throws the bow away rather than handing it over. When Lassïnce tries to take the violin, it sticks to Theirrée’s hand, leading to a battle in which he keeps trying to let go.

The manipulation is cleverly done, Theirrée juggling the violin until it seems to leap in his hands. Moment by moment, the timing is sharp, but it’s a long sequence, a long time to spend on the arrogance of Thierrée’s persona. His costars are given less space for characterisation: the men are stooges, while the three women are more glamorous but remote.

The show always seems conscious that its punchlines are clowning classics. It’s knowing about its own marvels, admiring its own free spirit a little too much.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments