The Dream/ Song of the Earth, Royal Opera House, London Without Warning, Old Vic Tunnels, London

With dazzling effects, the show goes on without Polunin the wonder boy

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.If anyone had set out on Wednesday night feeling short-changed by the absence of Sergei Polunin – scheduled to dance his first Oberon at Covent Garden but now in self-imposed exile – they had forgotten about it by the interval.

Yes, it would have been something to see the talented young Ukrainian in the role made almost 50 years ago for the young Anthony Dowell. In terms of sheer physical beauty (we'll overlook the tattoos), the 22-year-old was the closest any Royal Ballet principal had come to that gilded classical ideal. In terms of technique, in a role now legendary for its killer challenges, Polunin's debut was a lip-smacking prospect. In the event, though, his replacement, Steven McRae, gave him a run for his money. Also young but more slightly built, he seized the role and made it his: fiendishly fleet and pungently feral, if not quite wild.

The Dream, a 50-minute contraction of Shakespeare's play, is a fragile thing, delicate as cobweb. The cleverest idea of its choreographer Frederick Ashton was to set it, in design and gesture, in the period of Mendelssohn's music. This not only renders the piece ageless (who would guess it was from the 1960s?), and gives a Jane Austenish spin to the human lovers' tiffs, but invites reference to Romantic ballet's sylphs and wilis in the treatment of Shakespeare's fairies.

That said, no choreographer of the 1840s ever conceived of chorus-work so skitteringly fast. Dazzlingly, the feet of Titania's courtiers replicate the motion of moths' wings, though on first night the effect was sustained with effort, causing a back-row fairy to take a fairy tumble.

McRae's Oberon is not one for camp fairy-kingery. Sleek and severe, he streams like a swallow through sequential curling jumps, is testy with his capricious queen and indifferent to the humans' amorous problems. He sorts them out with his aphrodisiac magic, it seems, purely for the pleasure of wielding his power.

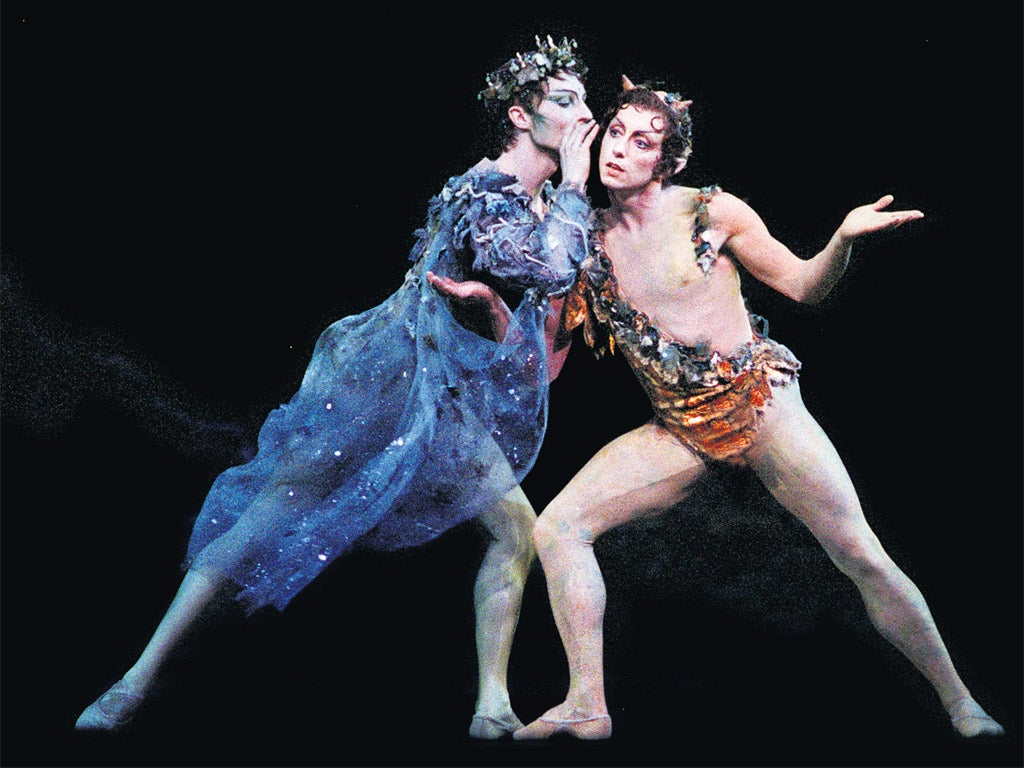

Valentino Zucchetti, the evening's Puck, had clearly been cast against a burlier master, but his hyper-nimbleness, throwing shapes in the air as sharp as a starry night, reduced any sense of mismatch. And no one would guess Alina Cojicaru's definitive Titania had been rehearsing for weeks with a different Oberon. The climax of her reconciliation with McRae, when she abandons herself to a fuss of ecstatic fluttering, may be the most erotic thing ever seen on that stage.

The other half of the bill, also from the 1960s, is its opposite – ruminative where Ashton is frivolous, stark where Ashton is pretty. Song of the Earth was Darcey Bussell's swansong when she retired five years ago. "That ballet says it all," said director Monica Mason, and she was right. Set by Kenneth MacMillan to music written by Mahler after the death of his daughter, it's as much about life as it is about loss. Those people who think you need technical knowhow to look at ballet could do worse than expose themselves to this pure shape- and pattern-making.

As in The Dream, at the centre is a trio: the Man (Rupert Pennefather), Woman (Tamara Rojo) and the shadowy Messenger (Carlos Acosta) – an envoy of death, but also a companion and guide. While dance and music both express the inevitability of his embrace, they also promise renewal.

The piece is full of moments you want to freeze and revisit. One such is when Rojo, standing isolated and small, leans forward like a reed in the wind – stillness as a gesture of ardent longing – then rises on her points with the swell of the orchestra and glides, in widening circles on rippling feet, as if unwinding from this mortal coil.

Without Warning ought by rights to leave your head brimming with dark thoughts, but it doesn't. Brian Keenan's book An Evil Cradling, about his four-year incarceration by terrorists in Beirut, is the spur to this project by choreographer Lizzi Kew Ross. At one point, the abducted heating engineer describes how he ventures a little dance in his cell, conjuring music from the rumbling of a vent – it's an invitation of sorts to a choreographer.

Without Warning's ambulant audience also get a chance to experience a novel venue – the cavernous tunnels under Waterloo Station. The lofty, rimmed-brick arches make a superb backdrop and acoustic. But the foreground shrieking, moaning, sidling along walls and contact-improv wrestling is random to the point of irritation. A generation has grown up since Keenan's dehumanising trials. It would surely better to give them information than this improvised horror. Stay at home and read the book.

RB double bill: ROH (020-7304 4000) to 5 Mar. 'Without Warning': Old Vic Tunnels (0844 871 7628) to Sat

Next Week

Jenny Gilbert seeks heat at Sadler's Wells's flamenco festival

Dance Choice

Richard Alston Dance Company premieres Alston's A Ceremony of Carols, as part of a triple bill. Danced to Britten's 1942 masterpiece scored for three-part treble chorus, solo voices and harp, it will be sung live by Canterbury Cathedral Choir. (Marlowe Theatre, Canterbury, Wed & Thu; Sadler's Wells, London 29 Feb & 1 Mar).

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments