Henri Michaux: The Other Side, Guggenheim Bilbao, review: We see only part of the artist's greatness

This show brings together about 230 of the artist’s visual works – including drawings made under the influence of mescaline and other drugs

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The Belgian poet and artist Henri Michaux (1899-1984) was an intensely shy man. When he and the French novelist and filmmaker Georges Perec had dinner together, neither spoke a word. Michaux held his hand in front of his mouth. Perhaps even masticating was a private matter. When the American poet John Ashbery interviewed Michaux at his Paris apartment in 1961 – he lived an itinerant’s life in Paris, moving from apartment to hotel room, seldom owning much, even destroying the scripts of his poems once he’d typed them up – the subject of the interview sat side-on to his questioner, head slightly averted, as if too bright a light was being shone upon him.

What in heaven’s name then would Michaux have thought about being presented in the Guggenheim Bilbao, the world’s most extravagantly plated armadillo of a museum? Fortunately for Michaux, he is somewhat tucked away amongst the gods. The exhibition happens on the third floor, in three galleries which lead into each other. Most of the galleries at this Guggenheim pick up on the outrageously eye-catching architectural panache of the building itself, at least to some degree, the way it always seems to be falling in on itself or emerging out of itself like some squirmy, river-thirsty living thing. Not so these three galleries, not really – except for the concave ceilings. Otherwise, it pretty much feels like gallery business as usual in here. And Michaux’s works suit a lack of splash because they are small and regular in their formats – many of them are framed rectangular pages extracted from notebooks, sketchbooks – we see that from the perforations which run down the left-hand edges of the pages.

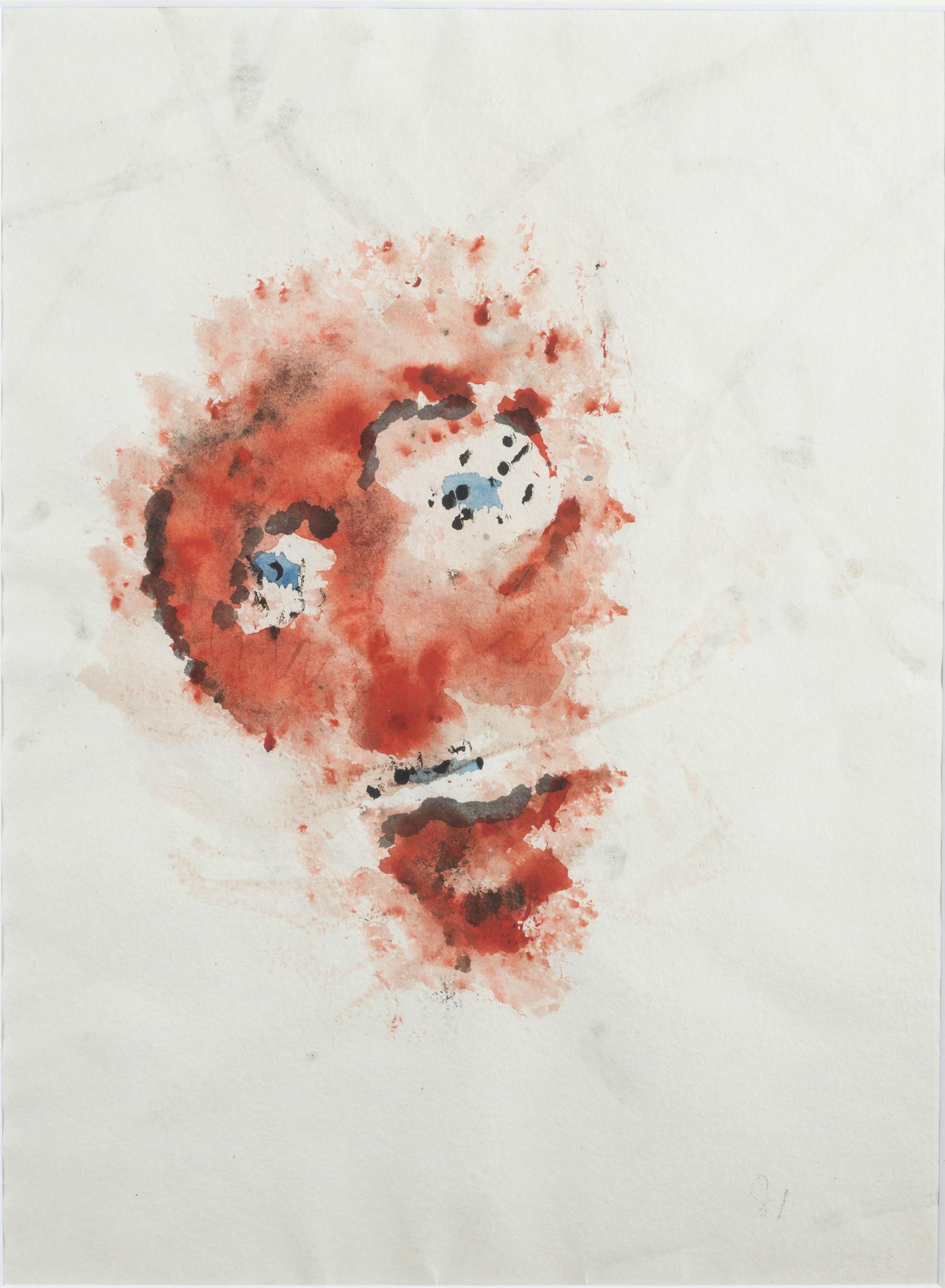

Michaux has been described as a neo-surrealist – which contains just the right amount of hedge-betting. He adopted what could easily be described as surrealist practices – belief in the aléatoire, for example – the role of chance in art-making, something known to every child who has ever been born. But his was chance combined with a degree of control. He would splatter-splash ink down on to a surface and then try to seek out the form – a face perhaps? – that was in the throes of being born. If he found it, he would encourage it along by adding a mark or two. He had no time for automatic writing – or for the pronouncements of that petty dictator André Breton. He wanted to encourage the mysterious to emerge from the depths of himself. His drawings and his paintings feel small and secretive, as if they have taken some considerable risk by revealing themselves thus far. Ashbery had asked Michaux what surrealism meant to him. It gave me La Grande Permission, Michaux replied. That marvellous formulation doesn’t need to to be translated.

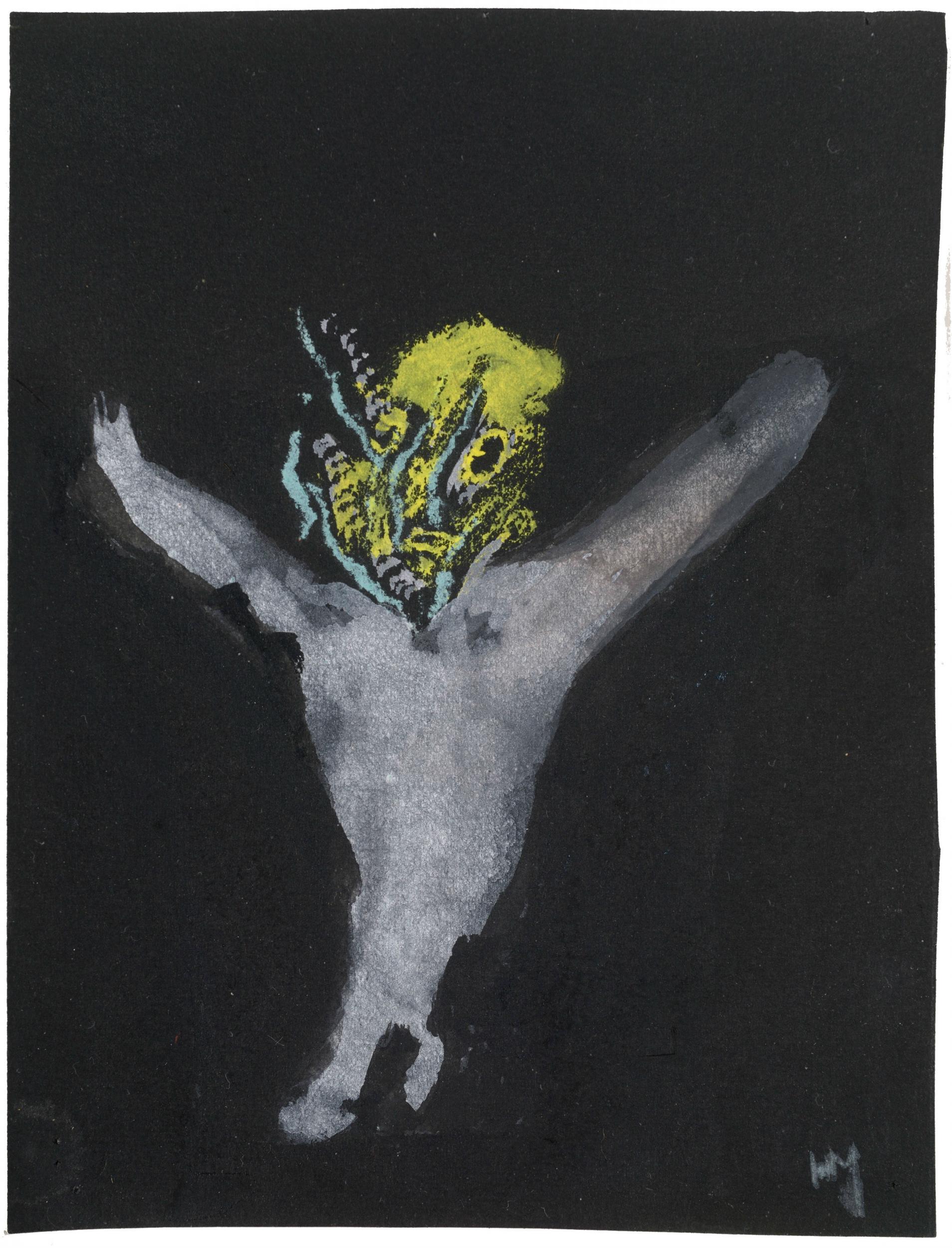

The exhibition is in three parts. It shows us how he worked with signs and extrapolated from notions of the alphabet (he was fascinated by Chinese calligraphy). It presents drawings made under the influence of mescaline and other drugs in the 1960s. And it sets his own work alongside some of the various ethnographical objects that he owned, often primitive totemic figures. There are more than 200 works in all, scratchings, combings, ant-like swarmings of mark-making; ghostly, mirror-warped faces swimming into view.

It all feels like an intense exercise in deep interior delving. But something is missing here. Something which makes this show much less of an achievement than it needed to be. For a start, quite a number of the works exhibited here are not very good. There are many others better than these. Who has done all the choosing? Was the Fondation Michaux in Paris properly consulted about this choice of works? There is also a total absence of poetry – except for the odd passing reference to a few book titles. The consequence of this absence is that we see only part of Michaux’s greatness. Half his life was devoted to poetry, and the other half to all this frenzied mark-making. The poetry opens up to us the full gamut of his extraordinary oddness in ways that the art often fails to do, and it is a world of bizarre humour. Why not quote from some of these poems? And why not humanise the man by putting a photograph of him on one of the walls of the gallery? (Yes, there are some tucked away down a side corridor).

This is therefore much less of a Michaux than it needed to be. In fact, it is something of a wasted opportunity. Why? Because the rigid, three-fold categorisation gives an excuse for a good deal of tedious and often self-defeating intellectualising. And if the catalogue had been made available in more than merely Basque and Spanish, Michaux enthusiasts who inhabit linguistic worlds others than these, would understand all this all too readily.

Until 13 May (henrimichaux.guggenheim-bilbao.eus)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments