Hamilton first night review: 'A magnificent achievement'

The most frenziedly anticipated musical in London since ‘The Book of Mormon’ lives up to the hype and is not to be missed, says Paul Taylor

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Alan Bennett once suggested that the world’s worst-taste T-shirt would read “I HATE JUDI DENCH”. By the same heretical token, it’s a fair bet that you could get yourself lynched right now if you were to walk round the West End with “HAMILTON SUCKS” emblazoned on your chest. This has been the most frenziedly anticipated musical in London since The Book of Mormon and the implacable publicity blitz (all together now for those 11 Tonys, the Pulitzer, the triple-platinum Grammy-winning cast-album et al) might lead even the most mildly rebellious soul to wonder if anything could possibly live up to this degree of hype.

I’m delighted to report that, for the most part, Hamilton manages to do so – quite exhilaratingly – and will disarm folk who think that a hip-hop musical about the Founding Fathers isn’t ideally placed to be a mega-hit on this side of the pond. “Join the revolution” is one of the main selling lines. Watching Thomas Kail’s production, you get a genuinely heady sense that Lin-Manuel Miranda – who wrote the book, music and lyrics – is offering us two revolutions in one here. The saga of the American War of Independence and a look at the teething problems of a new nation are presented in the shape of a bona fide game-changer of a musical – a (virtually) through-sung piece that blends rap, hip-hop, R&B and Broadway.

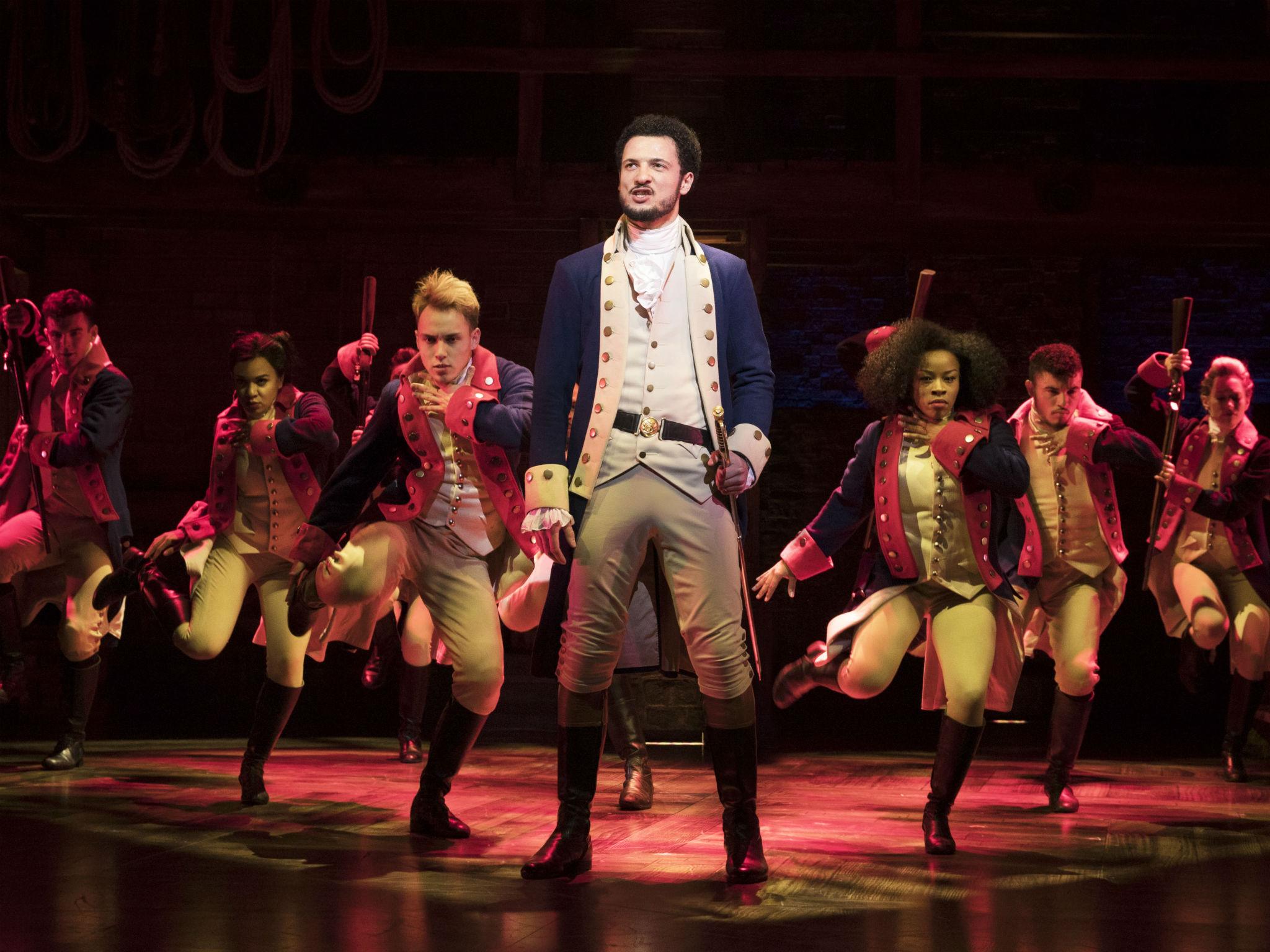

They may wear knee breeches and period costumes, but Hamilton and his band of brothers – the Marquis de Lafayette, John Laurens, and Hercules Mulligan – are played by performers of colour (the cast are of diverse ethnic backgrounds) and they rap in exuberant volleys of assonance and street-smart word-play, syncopated riffs and sprung rhythm (“Lock up ya daughters and horses, of course/It’s hard to have intercourse over four sets of corsets”). The idiom takes you right into the fiery metabolism and word-drunk wit of these youthful rebels, desperate to seize and mould a nascent nation.

Later on, presided over by Obioma Ugoala’s sombre and dignified Washington, cabinet debates become ferocious rap-battles with red-hot dropped mics. Hamilton and Jason Pennycooke’s superb, provocatively foppish Jefferson argue the toss over issues such as whether America should establish a national bank or provide aid to its former ally, France, in any upcoming conflict with Britain. The effect of the torrents of subversive coruscation (argumentative virtuosity translated from one style to another) and the unconventional casting feels wonderfully liberating and joyous. If this is “the story of America then told by America now” (as Miranda has pithily put it), you can appreciate why the similarly diverse company of the Broadway production felt entitled to treat Vice President Mike Pence, when he visited the show, to a salutary reminder about the duty to uphold American values.

This is a piece that urges America to take pride in its immigrant heritage (the composer’s family hail from Puerto Rico). It’s a land where a penniless “bastard, orphan, son of a whore and a Scotsman”, like Hamilton, could arrive in New York from the Caribbean and rise to be Washington’s right-hand man and the first Secretary of the Treasury – before being brought down by the country’s ur-sex scandal and meeting his premature end in a duel with the vice president, Aaron Burr. Just occasionally you may reckon that the author overplays his hand. You can almost see the waggle of an “Applause” placard on the line “Immigrants – we get the job done!” But, in general, the sentiment is fervent and far from facile.

Miranda originated the title role on Broadway. Here it goes to Jamael Westman who delivers a very intelligent and well-sung performance, while coming over as perhaps too disciplined to give full turbulent life to this relentless, pell-mell, sometimes rackety prodigy who can toss off 51 of the Federalist Papers in six months, does everything as if is he is running out of time, and likens his raw, ravenous state, at the start, to the condition of America: “Hey yo, I’m just like my country,/I’m young, scrappy, and hungry/And I’m not throwing away my shot!”. Giles Terera is splendid as Burr, the frenemy and nemesis who is Salieri to Hamilton’s Mozart, all silky, privileged containment and disengaged calculation as opposed to his fellow orphan’s committed impetuosity. “If you stand for nothing, Burr, what’ll you fall for?” asks Hamilton with scathing succinctness. He effectively seals his fate by endorsing Jefferson rather than Burr in the 1800 election. While he’s never agreed with the former about anything in his life, at least “Jefferson has beliefs. Burr has none.” The pair’s intertwined destinies play out as a beautifully articulated part of the proceedings.

There are several knockout numbers, among them Terera’s jivey, obsessive “The Room Where It Happens”, the hypnotic and danceable plaint of a man who feels politically excluded. Rachel John is in tough, ravishing voice, rhapsodising about how good it is to be alive now and living in New York, as Hamilton’s smart proto-feminist sister-in-law, Angelica Schuyler, who is his soulmate in unappeasable yearning. It may be unfair to the original but it’s a terrific joke that George III – hilariously played by Michael Jibson as a camp clump of twinkling malice in full royal regalia – sings of the political break-up in the jaunty tones of a 1960s Britpop number: “You’ll be back/Soon you’ll see/You’ll remember you belong to me”. He can’t believe that the presidency is not for life, unlike kingship, and settles back, with condescending relish, to watch his former subjects tear themselves to pieces.

Kail’s production is not perfect. It unfolds with seamless fluency on David Korins’s handsome open-stage set, with its bare brick walls, revolve, coils of rope and other maritime paraphernalia. The ensemble, in their sexy torn-off costumes, give the show high-energy propulsion, but their movements sometimes look banal. When they sing of “The world turned upside down!” after the decisive victory at Yorktown, they clamber aloft and hold up inverted furniture – evidently unafraid of the obvious.

If I sometimes wanted the piece to go further (why not an African-American woman as George Washington?), this is doubtless just a tribute to the show’s instigative powers of suggestion. Towards the end, though, for my taste, it starts to tackle its serious developments with a po-faced solemnity that is faintly risible. The death in a duel of Hamilton’s son; the fall-out from the sex scandal (Rachelle Ann Go overacts the role of his wife, Eliza); the preoccupation with the eyes of history and with legacy – these are weighty subjects, true, but the show begins to feel as if it’s a little in awe of itself in the way it deals with them. I fell to musing what revivals of Hamilton might be like in years to come when it is not such an institution and directors have more latitude.

These are relatively minor cavils, though, about a piece that, in the main, is obviously a magnificent achievement. Miranda’s synthesis of the historical material is phenomenal, as is his supple control of the diverse musical idioms. Two eras train light on each other here and, at its best, the show creates the impression that it is not merely dramatising Hamilton’s revolution but, in its artistic choices and spirit, is carrying it forward. Patience may be required to secure tickets, but on no account is this to be missed.

‘Hamilton’, Victoria Palace Theatre, London. Currently booking until 30 June 2018 – hamiltonthemusical.co.uk

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments