First Night: The Bolshoi Ballet, Royal Opera House

Bigger, bolder, stronger: Bolshoi returns to London with an epic 'Spartacus'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The Bolshoi Ballet is one of the world's great companies, among the best-known names in dance. Anticipation has been high as the Moscow dancers return to London for a three-week season, with fans rushing to the box office. Russian ballet companies being famously unpredictable, the same fans have been rushing back at each rumour of changed casting, determined to get the right stars.

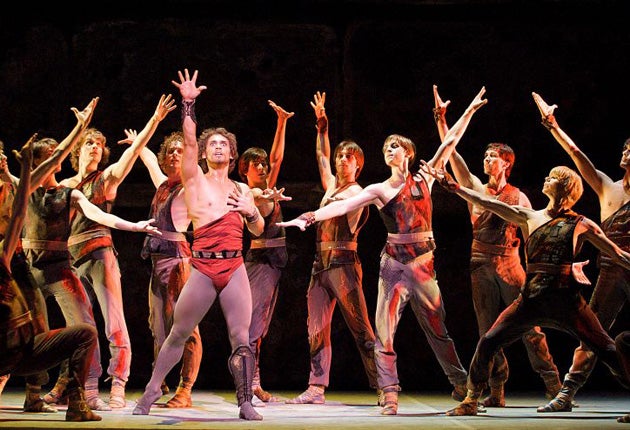

For most, the right star is Ivan Vasiliev, who danced the title role in Spartacus on the season's first night. Vasiliev made a big impact at the last Bolshoi visit three years ago, as a teenage virtuoso. Now 21, he's opening the season in one of the biggest roles in the Bolshoi repertory.

The hype, and the real excitement, were feverish. Both turned out to be justified.

Vasiliev is spectacular: in technique and in authority. He's physically stronger now, broader in the shoulders, with wild eyes and wild curling hair. Perhaps most surprisingly, he makes a natural Spartacus.

Though Yuri Grigorovich's ballet is still one of the Bolshoi's defining works, the company has moved away from his blockbusting style in recent years. Spartacus demands enormous power – huge leaps, one-handed lifts – while today's Bolshoi men often have a slighter, perhaps nimbler build. Yet this is still an iconic role. Foreign dancers such as Carlos Acosta have been eager to try it.

Vasiliev, trained not in Moscow but at the Belorussian Ballet School, certainly has the jumps. London audiences have already seen his soaring leaps. Now they're even loftier, with a plush spring as he leaves the ground. He holds shapes brilliantly in the air, arching tightly mid-flight. Lifted by his own army, Vasiliev's Spartacus looks like a figurehead, or a Soviet poster.

He also developed greater stamina. The extravagant Bolshoi lifts are confident – even the jaw-dropping one-hander where Nina Kaptsova, as Spartacus's wife Phrygia, balances on his upstretched palm, her feet higher than her head.

If Spartacus needs brute strength, it also needs sincerity. Grigorovich's choreography is not subtle. Noble gladiators oppose wicked, wicked Romans. Spartacus is generous in victory, only defeated through treachery. His opponent Crassus is given to sneakiness, cruelty and notably camp orgies. Where Phrygia is noble and devoted, Crassus's mistress Aegina waylays and seduces the rebellious slaves, doing a pole dance in triumph. Aram Khachaturian's music blares with trumpets and jangles with percussion.

In other words, Spartacus is thoroughly kitsch. It's survived this long because the Bolshoi danced it with innocent ardour, heroic conviction: look knowing in this, and the whole thing would sink. But today's Bolshoi dancers haven't grown up under the shadow, and the protection, of a Soviet state; they've lived with capitalism and danced a much wider repertory than their predecessors. Can they still believe in Spartacus?

On recent visits, the conviction had definitely wavered. I've seen some stodgy performances, when sagging energy gave you all too much time to notice the ballet's sillinesses. This time, the Bolshoi has gone back to believing in it. Gladiators and shepherdesses hurl themselves into Grigorovich's big, repetitive steps, dancing with abandon. There are still weaker moments; despite the best efforts of Alexander Volchkov and Maria Allash as Crassus and Aegina, the Roman orgies do go on.

Vasiliev's hero pulls it all together. Grigorovich's Spartacus turns to rebellion after being forced to kill a fellow gladiator. In his big solo, he reaches out with both hands. With Vasiliev, it's the gesture of a man with blood on his hands. His horror leads directly into the clenched-fist gesture of rebellion. Vasiliev does go over the top in the final battle, but he can also find subtleties even in this choreography. The whirling turns can slow, becoming weighty as he agonises over the future.

The other principals are strong. Kaptsova is a long-limbed Phrygia, going from gently drooping lines to heroic resolution. Maria Allash has huge fun as Aegina, flashing wicked smiles in all directions. Alexander Volchkov struts through the goose-stepping Roman steps, with a touch of mania in his fight against Spartacus. Pavel Sorokin conducts the orchestra of the Bolshoi Theatre in a gleeful performance of Khachaturian's flamboyant score.

Bolshoi season runs until 8 August. Box office 020 7304 4000

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments