Damned by Despair, Olivier, National Theatre, London

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

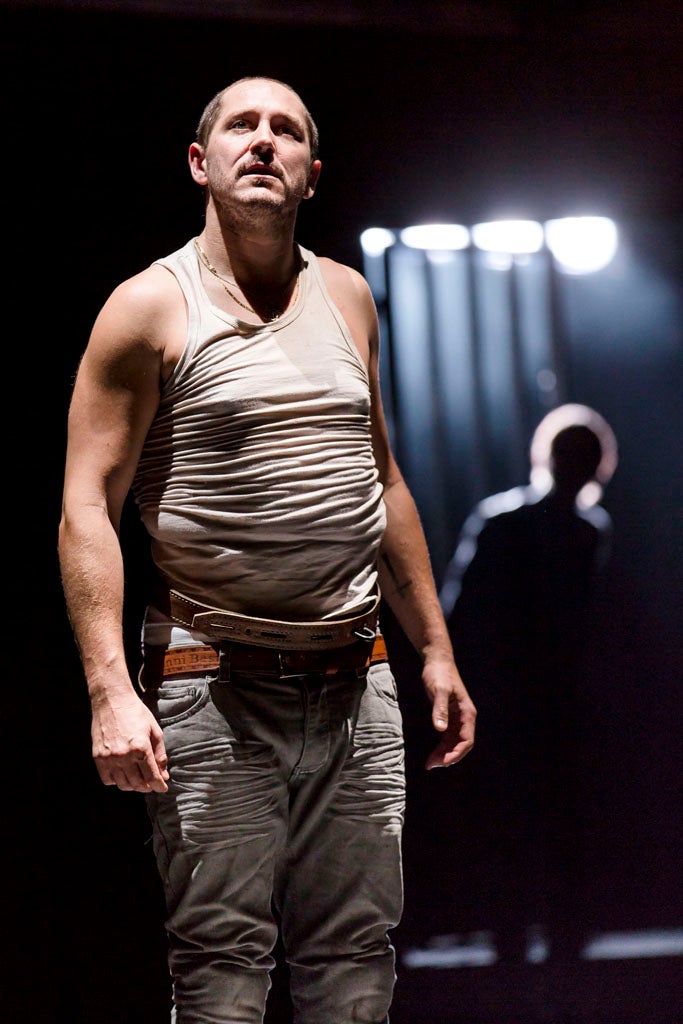

Your support makes all the difference.Spare a thought for poor Bertie Carvel. One minute, he's a camp brute of a headmistress swinging schoolgirls round by the plaits in the rip-roaring hit of Matilda. The next, he's being brutish – and strangely camp – all over again, this time, though, as a murderous Neapolitan thug in Damned by Despair, a venture that looks set to go down in history as one of the National Theatre's rare turkeys.

The reasons why Tirso de Molina's 1625 play is rightly considered one of the masterworks of the Spanish Golden Age are only fitfully apparent here in Bijan Sheibani's erratic staging – in the Olivier, as part of the Travelex £12 season – of a tonally messy new version by Frank McGuinness.

Full of black ironies about the knotty relationship between faith and God's mercy, the play dramatises the intertwined destinies of two men. Obsessed by the problem of his own salvation, the pious hermit Paulo (Sebastian Armesto) falls for the trick practised on him by the Devil who appears in the form of angel and is portrayed here as a bony androgynous practical joker by Amanda Lawrence.

Paulo is told that he will come to exactly the same end as one Enrico but when this stranger proves to be Carvel's agitated braggart of a baddie, the hermit despairs. If he's bound for the eternal flames in any case, the hermit reasons that may as well go in the fashion of his supposed doppelganger.

It's a penetrating piece that pits the spiritual pride that presumes to want a fixed deal with God against the flexibility of a man who, though wicked, remains open to divine forgiveness. To the agnostic mind, it all seems, erm, damnably unfair, especially as Enrico is equipped with a redemptive soft spot for his crippled dad. In the original, a darkly comic dimension co-exists with an overall deadly seriousness.

Here, though, a Reservoir Dogs-style jokiness in the updated gangster scenes sits uneasily alongside, say, ethereal apparitions of a flaxen-haired boy-treble singing of God's mercy as he processes down the central aisle or the laughably sentimental bits where Enrico goes all gooey over papa. The show has several not-quite-saving graces but it feels incoherent and underpowered and has none of the fiercely flamboyant concentration of effect achieved by young Turk Stephen Daldry when he directed this epic-scale play at the tiny Gate Theatre twenty years ago.

To December 17; 0207 452 3000

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments