What's the fuss about Pinter?

The Nobel laureate's No Man's Land has earned rave reviews. But what do three Pinter virgins – and our critic – make of it?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Matilda Egere-Cooper, urban music journalist: 'Obscure and exhausting'

I've never seen a Harold Pinter play. From what I hear, his work has long been revered for its pointed sense of irony, drama and multifarious characters, all evident in this revival of his 1975 classic. So forgive me for thinking that, after the first 15 minutes, I'd rather be somewhere else.

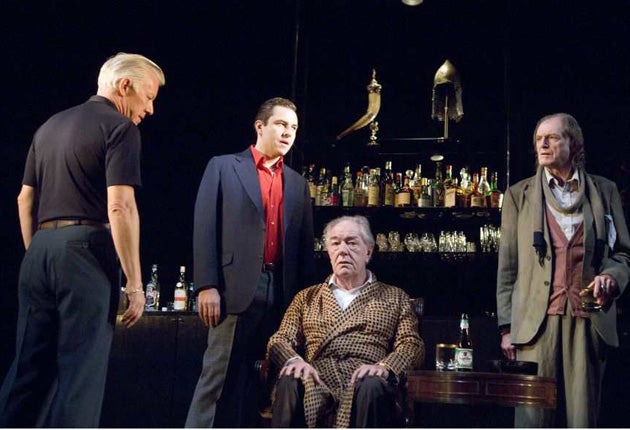

Don't get me wrong – David Bradley's Spooner made me smile, with a performance that was completely at ease with Pinter's sprawling dialogue and colourful vocabulary. He looked the trampy part and shared his love for a good drink or five with his accidental and troubled pub buddy, Hirst (performed by Michael Gambon), suggesting Spooner was quite content in an intoxicated nirvana which seemed to be the only place to go for failed poets, or just failed old men.

But the whole premise seemed obscure, exhausting and convoluted. There were way too many anecdotes to keep up with, not helped by the limited action of the characters on the set. The various trips down memory lane that Hirst and Spooner take could have been helped with a bit more visual variety.

Then there's Foster (David Walliams, 'Little Britain') and Briggs (Nick Dunning) – the two man servants. Dunning's mug was convincingly mean, but I just didn't buy it with Walliams.

Act 2 was a lot better. The champagne breakfast scene between Briggs and Spooner was quick-witted. Add to that the moment Hirst realises he doesn't know who Spooner is after a lengthy discussion about the sexual conquests of their youth – the comic timing was just superb. But I doubt newcomers to Pinter will be instantly taken with this writer's knack for one-liners, empty spaces and incomprehensible dialogue. It's highbrow all right, but a touch overwhelming, too.

David Knott, political lobbyist: 'Don't expect to feel uplifted...'

I went to see 'No Man's Land' pushing to the back of my mind the hours spent considering Pinter at school. I encouraged myself with the thought that I usually enjoy trips to the theatre. I'd also never previously seen Michael Gambon on stage, which was also a draw.

The first half was a forlorn affair. I found it difficult to empathise with the characters: Spooner is a professional drunk masquerading as a poet, Foster and Briggs are both aggressive, freeloading homosexuals, while Hirst is a forgetful, whisky-sodden intellect looking for sympathy.

This is not to say that the cast is not good, since – perhaps with the exception of Walliams' overstated menace – it is. But, to me, the dialogue often sounded clumsy and detracted from any overall narrative.

Part of the amusement of any play is to examine the set, which in this case did contain a number of interesting items. The well-stocked bar is attended at regular intervals by the cast. This was supplemented by curios that might have been on loan from the British Museum: an ivory drinking horn, gleaming Moorish helmet, and an interesting ochre-coloured lamp in the form of the Buddha.

In the second half, Hirst's room is bathed in light and the mood is, for a time, more upbeat. There is a champagne breakfast and some genuinely amusing banter as he and Hirst reminisce about Oxford, Dijon, and women that they have known. But this does not last for long, and a wintry aspect soon overshadows the remainder of the play, with the dialogue freezing once more into a fog of non sequiturs. It's not that I wouldn't recommend the play: just don't expect to feel particularly uplifted as you exit.

I have a feeling that this is not Pinter's strongest work. I read the Nobel citation afterwards, which said he's known for his "comedy of menace" – and I think I can see that 'No Man's Land' was trying to produce that.

Susie Rushton, editor and columnist: 'Where's the joke?'

There are laughs right from the first words of 'No Man's Land': "As it is," says Michael Gambon as Hirst, accepting a drink. At least a dozen people in the audience respond straight away with the kind of pre-prepared titter that signals, "I understand this." I'm nonplussed. The man wants his vodka served straight up. Where's the joke?

What followed certainly wasn't laugh-out-loud funny, or very interesting: a barmy old drunk, dressed like a tramp, has latched on to another rheumy-eyed boozer, and joined him back at his bachelor pad. They talk nonsensically at each other. There are pauses. Rolled eyes. They drink whisky. So far, so route 137 night bus. We discover they have met that night on Hampstead Heath. I think of George Michael; but, no, Hirst and Spooner are not two aged cruisers. They are literary men, and may have known each other before – Oxford, was it?

By the end of the first half, ambiguity becomes confusion when Foster and Briggs stride into the room. My impression that this is a play about relations between gay men returns, particularly as David Walliams' mode is the same campy-menacing sidle he used in 'Little Britain'. Actually, if 'No Man's Land' is about anything, it's about aggression. Everyday, closing-time, moody-old-bloke-aggression. Care much about the subtleties of that? Me neither.

In fact, the only one of these four who looks capable of throwing a punch is Briggs, the manservant. His posturing – puffed-out chest – recalls another Pinter play I've seen, 'The Homecoming', during which I remember feeling anxious blood might spill. But, tonight, I'm never really touched by the thrill that violence could break out. Instead there's sarcasm, put-downs, defensiveness. I zone out. Only Gambon's grumpiness and leonine voice can bring me back to the shuffling-about onstage.

The second half is marginally less rambling. Daylight breaks. Spooner is still hanging around, the guest who won't take a hint and bog off home. With fake magnanimity, Foster and Briggs serve Spooner a champagne breakfast, which he accepts at face value. He looks grossly sweet as he tucks in. The dialogue becomes more nimble as Hirst accuses Spooner of sleeping with his wife back in the Thirties, and by the time he roars "I'll have you HORSEWHIPPED!" I'm quite gripped; it's like the shouty bit in 'Withnail and I'. Gambon works himself into an extraordinary frenzy, his old body shaking, spittle flying across the stage. He is truly brilliant – but he'd be brilliant with a bucket over his head reciting the collected lyrics of Kylie Minogue.

And what of Pinter, the Nobel laureate? That there's no "story", I can forgive, but this theatre goer didn't find much poetry, or complex emotion, in the play; it seemed poorly structured; its focus was narrow. I'm guessing that Pinter is a bit of a moody bloke himself. If he's our greatest living dramatist, as most of the audience clearly believed, I sure don't want to see the other guys' plays.

Paul Taylor, 'Independent' critic: 'You need to persevere with Pinter'

In some respects, being a "Pinter virgin" is a bit of a contradiction in terms. Pinter's influence has been so wide and deep that we have all, even people who haven't yet seen one of his plays, lost our innocence to him. He's like part of the water supply or the air we breathe. To claim to be a Pinter-virgin is rather like (in certain parts of the world) suggesting that you are a fluoride virgin. The adjective "Pinteresque" has entered the language and everyone has at least a vague notion of what it means. It has to do with those famous pregnant pauses, a sense that language (used as a weapon or a mask) is what divides people rather than brings them together, and the feeling of menace and unease (often very funny) lurking beneath what is said. And Pinter's poetic and hilarious manipulation of idiom and register has spread far beyond the theatre. As Patrick Marber remarked when directing a revival of 'The Caretaker' (1960), nascent within that play is the greater part of Sixties comedy, from Pete'n'Dud to 'Steptoe and Son'.

So why might a first-timer to a drama such as 'No Man's Land' (1975) find it slightly daunting? It's partly because Pinter plays the rules of the game in Pinterland with uncompromising stringency. What are the rules? Well, as Tynan once said, where most playwrights devote their technical efforts to making you wonder what will happen next, Pinter deliberately leaves you puzzled as to what is happening now. Then there's this dramatist's belief that "One way of looking at speech is to say that it is a constant stratagem to cover nakedness," with the plays acting as the means by which the characters betray that underlying nakedness. Then there's his use of subjective memory. In 'Old Times' (1971), a female character declares that "There are some things one remembers even though they may never have happened. There are things I remember which may never have happened but as I recall them so they take place." Consciously and competitively deployed, such "memories" become (uproariously in 'No Man's Land') weapons in the fight for territory, status, possession of the past.

Like many classic Pinter plays, 'No Man's Land' is about the reaction to an intruder who threatens the status quo ante. The subtlety that gradually emerges in this play, though, is that Spooner, the seedy Prufrockian failed poet, is the alter ego of his host, the moneyed litterateur, Hirst, and that his predatory intrusion also represents an abortive attempt to reconnect Hirst to life and to his creativity and to save him from the bitter stalemate of old age. Mysterious, bleakly beautiful and very funny, 'No Man's Land' demonstrates that though it may take a little while to latch on to the laws of Pinterland, it is well worth the effort.

'No Man's Land' is at the Duke of York's Theatre, London WC2 (www.dukeofyorkstheatre.co.uk), booking to 3 January

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments