Up to their necks: The singular joys of appearing in Samuel Beckett

No playwright pushes actors to the limit quite like the Irish absurdist

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Samuel Beckett liked his actors to be up to their necks in it. In Happy Days, the protagonist’s head pokes out of a mound of earth; in Play, characters are incarcerated in urns; in Endgame, it’s dustbins. Sometimes he gets rid of their necks altogether: the actress in Not I must have her head strapped down, her body clamped still, so just her mouth can be lit. Demanding? Not half – and not just physically. Beckett’s bleak (if also blackly comic) texts also require actors to give up their innermost self; his favourite direction was “don’t act”.

He was prescriptive, not to mention constrictive, in his language, pauses and stage directions too. Beckett died in 1989, but even modern productions must follow these exactly – or risk being closed down by the estate. And the shorter, later plays, especially, are an exact – and exacting – science. Lisa Dwan, performing a trilogy of them at the Royal Court this month, describes his writing as “homeopathic… where everything is distilled and distilled until what is left is so potent and clear”.

Not that his work has always been viewed as clear. Many plays baffled, even angered, critics and audiences when first staged, and his work still has a reputation for being difficult. Yet today’s theatregoers are apparently happy to ditch the “but what does it mean?” bleating, and embrace Beckettian absurdity.

Dwan’s trilogy is a sell-out, and will transfer to the West End in February; not, perhaps, the home you’d expect for the just-a-mouth monologue Not I, the carefully choreographed pacing of Footfalls, or for Rockaby, where a chair mechanically rocks an old woman as her recorded voice reflects on the end of life. Then there’s Happy Days, opening at the Young Vic later this month, whose run has already been extended owing to demand. It stars Juliet Stevenson as the resourceful housewife Winnie, in the first half buried up to her waist, in the second up to her neck; she chatters on endlessly to her (near-silent) husband to ward off despair. Meanwhile a version of Krapp’s Last Tape, starring Tom Owen as the old man broodingly listening to old tapes of his younger self, is on tour.

Talk to any of these actors and they all say the same thing: Beckett’s work is the most challenging they’ve ever tackled – physically, emotionally and formally. And that’s not to mention the trials of learning his often maddeningly fragmentary scripts. Owen, who played Compo’s son for 11 years in Last of the Summer Wine, says he “couldn’t make head nor tail of” Krapp’s Last Tape when he first read it, but came to welcome the contrast with his less arduous TV stint. The Beckett piece may be short – 55 minutes – but Owen says he feels he’s been on stage for about three hours. “You’re mentally and physically exhausted but you have that after-glow, that ‘wow’ – and that doesn’t happen often in an actor’s career.” The piece is partly challenging due to its double structure: not only acting, but reacting, to the tapes, to the past. It’s another formal constriction Beckett loves: the pre-recorded, disembodied voice (also potently present in Dwan’s Footfalls and Rockaby).

Juliet Stevenson found actually performing Beckett offered her a way into his work. “I thought he was pretentious and unavailable,” she confesses. “But when I did Not I and Footfalls with Katie [Mitchell, for the RSC in 1997], it was a complete revelation: to come inside the material, and explore it and inhabit it. And I realised he really is a genius.”

Did she have any reservations about taking on Winnie? “Piles of reservations! I was quite agonised. Because it’s frightening … [But] I would not have forgiven myself for not saying yes.” And it is simply physically scary – an early rehearsal involved her being buried in steaming compost in Regent’s Park: “the claustrophobia set in really quickly, before they got to the waist – I didn’t like it. But [Winnie’s] long been in that situation. So whether or not she still has to fight claustrophobia, I don’t know; I suspect there are moments when she does. But what’s for sure is that she talks in the way that she does, and as much as she does, to keep the demons at bay.”

Being buried obviously limits an actor’s physical tools of communication; in Happy Days it comes down to “eyeball movement and breath” – even if such tiny gestures are detailed in the script with precision. Stevenson likens it to a musical score: “His rhythms are astonishing. And I think you have to observe [them] as you would observe Mozart’s or Bach’s … they just reveal [Winnie’s] internal life.”

So can Beckett’s restrictions actually be liberating? “It feels restrictive when you’re trying to learn it, and you swear and scream and shout at him, but finally [it is]. Discipline is always liberating.”

Stevenson has had several such encounters with Beckett; there was also Play which she recorded in 2001 for the “Beckett on Film” series, in which she found herself in a clay pot in some purgatory or hell, recounting an affair with a similarly incapacitated Alan Rickman and Kristin Scott Thomas. “It’s interesting, isn’t it, Beckett so often wants to contain women,” muses the woman who also found that performing Not I involved her head being clamped to a small hole in a tower, eight feet up in the air.

Lisa Dwan’s production of Not I also entails elaborate physical preparation: namely, painting her face in black make-up, blindfolding her eyes and putting tights over her head. Dwan’s head is then fastened in a tall wooden structure, with just her mouth coming through a hole, while her arms are strapped, crucifix-style, so she can’t move a millimetre. The text is fiendish too: a feverish stream-of-conscious gallop through a trauma-ridden life, which Beckett wanted delivered “at the speed of thought”. She nearly manages it, rattling through Not I in nine minutes: so fast, in fact, that she must use circular breathing and doesn’t have time to swallow: “I can’t eat things that produce a lot of saliva, because that’s a real problem!” After one show, she even discovered she’d given herself a hernia…

“I don’t know which is more anxious-making: the claustrophobia, the head harness, trying to memorise it, the speed, the actual trauma the piece summons … let’s just say it’s quite a cocktail,” says Dwan wryly.

Impressively, she memorised it in a just a few days in 2005, to convince the initial director (Natalie Abrahami, also helming Happy Days) she was the only one for the part. Dwan was schooled by the greats, mind. Beckett’s favourite actress, the legendary Billie Whitelaw, for whom he wrote Not I and Footfalls, invited Dwan to her house to give her Beckett’s notes.

It gave her permission, Dwan explains, to be less intimidated by Not I, or Beckett’s “don’t act” diktat. “He wants the real thing, an access point to your entire nervous system. You know that if you succumb to exactly what he wants, it works. I don’t think I’ve ever trusted another writer – I don’t think I’ve ever trusted anybody – to the extent that I trust him.”

‘Not I, Footfalls, Rockaby’, Royal Court until 18 Jan, Duchess Theatre, 3 to 15 Feb. ‘Krapp’s Last Tape’, Rose Theatre Kingston tomorrow, and on tour. ‘Happy Days’, Young Vic, 23 Jan to 8 Mar

Beckett actors recall the heaven and hell of his plays...

Billie Whitelaw

On Not I and Footfalls: “Me, I recognised an inner scream in Not I, something I’d been sitting on for a long time, and whatever it was connected with me very fundamentally … It’s physically very painful to do. Each play I do, I’m left with a legacy or scar.”

Peggy Ashcroft

On Happy Days: “Winnie is one of those parts, I believe, that actresses will want to play in the way that actors aim at Hamlet – a ‘summit’ part … I couldn’t play Happy Days again. But it is one of my most intense theatre memories. There’ll never be such pleasure again – or such agonies.”

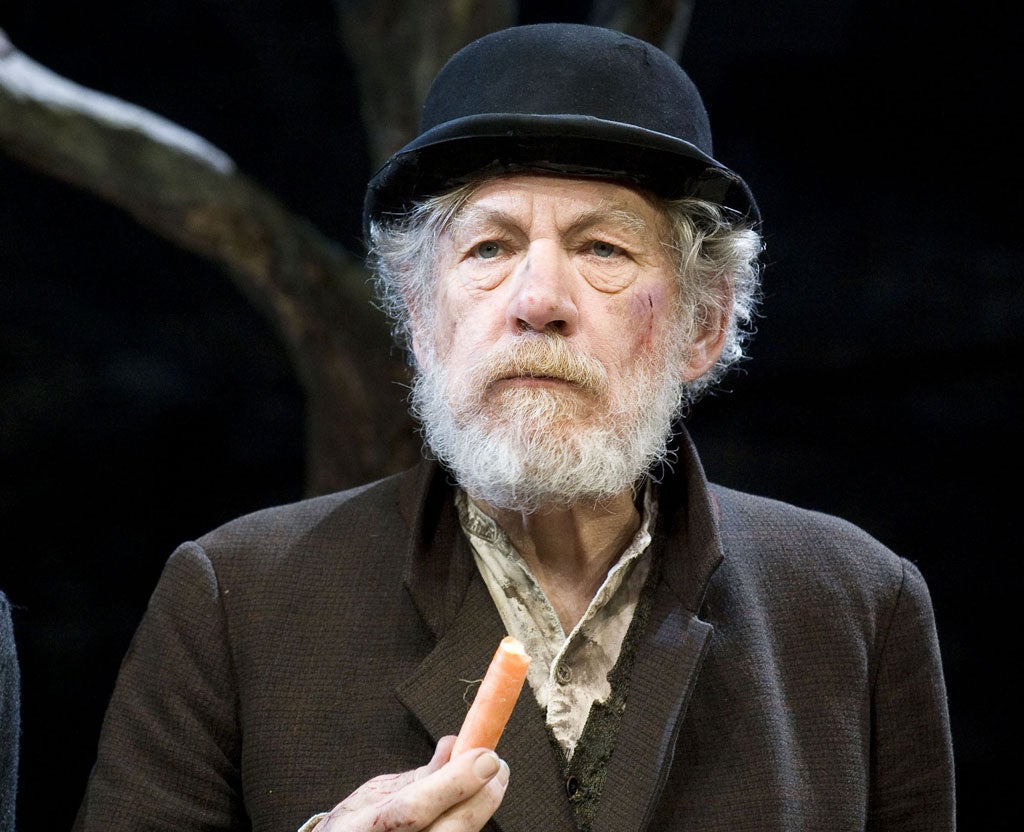

Ian McKellen

On Waiting for Godot: “I thought this was the most difficult play in the world … but now I’ve done it, after just five weeks, I realise it is an absolute masterpiece. I think the world is divided between those that think Waiting for Godot is absolute rubbish, and those who know it to be absolutely vital.”

Simon McBurney

On Endgame: “Beckett is special, Endgame particularly so. It is unlike anything else I have played: fastidiously specific, utterly elusive. At any one moment in the performance, you will be aware of someone laughing hysterically, another weeping, while others sit silent, astounded or baffled.”

Fiona Shaw

On Happy Days: “I have always had a troubled relationship with Samuel Beckett … I found my lines hard to learn. Images did not build in the mind, they disintegrated instead – Beckett’s writing is all interrupted thought. It is as if he wrote in reverse, ideas appearing as X-rays. This struck me as ungenerous and cruel of him … Then, a few weeks into rehearsal, I saw a light in the darkness.”

Alan Rickman

On Play: “I’d done enough research, having talked to people who had been in that piece of work, to know that it had literally driven people nuts. ‘You are mentally and physically exhausted but you have that afterglow, that “wow”’

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments