The Tempest: Why the RSC got it wrong

The danger in relocating The Tempest to South Africa is that real-life events move more quickly than any drama, says Paul Vallely

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Can Caliban be a noble savage in the age of Jacob Zuma? The elections in South Africa this week coincided with the end of the tour of the Royal Shakespeare Company's production of The Tempest. The critics had given the show, which was a joint venture with the Baxter Theatre Centre in Capetown, high praise for re-interpreting the Bard's valedictory play as a study of the end of apartheid. But politics is moving too quickly. Already this Tempest seems hopelessly out-dated.

Caliban has undergone a wide range of paradigm shifts since he first appeared in his filthy gabardine in 1611. In his early days he was the personification of the natural depravity of man, a drunken beast untamed by tender education, on whose nature nurture could not stick – and whose nature was, as Hobbes wrote less than 50 years later, solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.

But, less than two decades on, Dryden coined the phrase "the noble savage". Out of that, and the political optimism of Rousseau, came a view of Caliban as "nature's gentleman", whose instinctual poetry stood as a reproach to the corrupting civilisation which had plunged the continent of Europe into an unending series of wars.

Thereafter Caliban swung between victim and villain with the fashion of the times until, by the latter half of the 20th century, he had come to be seen as an oppressed representative of the Third World bowed by the exploitation of European imperialism and then global capitalism. They were big, easy targets.

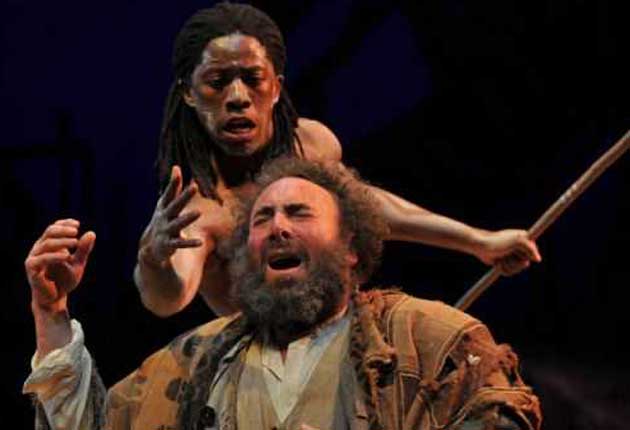

And now we have the RSC end-of-apartheid version. Sir Antony Sher's Prospero is a foul-tempered, dyspeptic, whip-in-hand white colonialist. And the South African actor John Kani plays the part of Caliban with what one critic described as "a stoical, Mandela-esque dignity".

No doubt the idea would have resonated in the early 90s when Nelson Mandela walked free from jail and became South Africa's first black president. But much rancour has flowed under the political bridge since those golden days. Mandela was succeeded by Thabo Mbeki, a reserved intellectual, at ease with quoting Shakespeare or Latin tags, but who systematically undermined the post-apartheid constitutional settlement, neutering parliament, factionalising the security services, politicising prosecutions and suppressing debate.

And now Jacob Zuma has assumed power. This political chameleon is a throwback to an earlier time. He is charming and charismatic, but his crude populism, his "Bring Me My Machine Gun" anthem and his "100 per cent Zulu Boy" sloganeering summon the tribal Big Man stereotype which has served Africa poorly in the past. He has, of course, had charges against him of corruption, racketeering and money laundering dropped, and he has been found not guilty at his trial for rape. But it is all a far cry from the beloved dignity, magnanimity and secular sainthood that was Nelson Mandela.

This shift in political model only exposes the other deficiencies of the RSC's sentimentalist approach. Mr Zuma may have been acquitted of rape, but Caliban rejoiced in the charge and gleefully boasted that, had not Propsero intervened, he would have "peopled else this isle with Calibans". Shakespeare leaves us in no doubt that Caliban is "a savage and deformed slave". His contrast is not between Caliban and Prospero, but between Caliban and Ariel, who personify conflicting traits within Prospero's character.

Shakespeare is not into facile finger-pointing; he is dealing with the complexity of truth and rec- onciliation in the human psyche. If politics has to be part of that, let it at least be up to date. Mbeki as Prospero, with Zuma as Caliban, now that would be political theatre of altogether more interest.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments