Platonov, Ivanov and The Seagull: David Hare is determined to prove young Chekhov is more glorious than old Chekhov

‘He was hot and romantic’

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Think you know Chekhov? Think again. No lesser figure than Sir David Hare is on a self-declared campaign to shake up audience’s assumptions about the dramatist. For all the umpteen Chekhov revivals, we largely see only four plays from the turn of the 20th century: The Seagull, Uncle Vanya, Three Sisters and The Cherry Orchard. The tragedy is he died in 1904 at just 44, and left us with so little. Or did he?

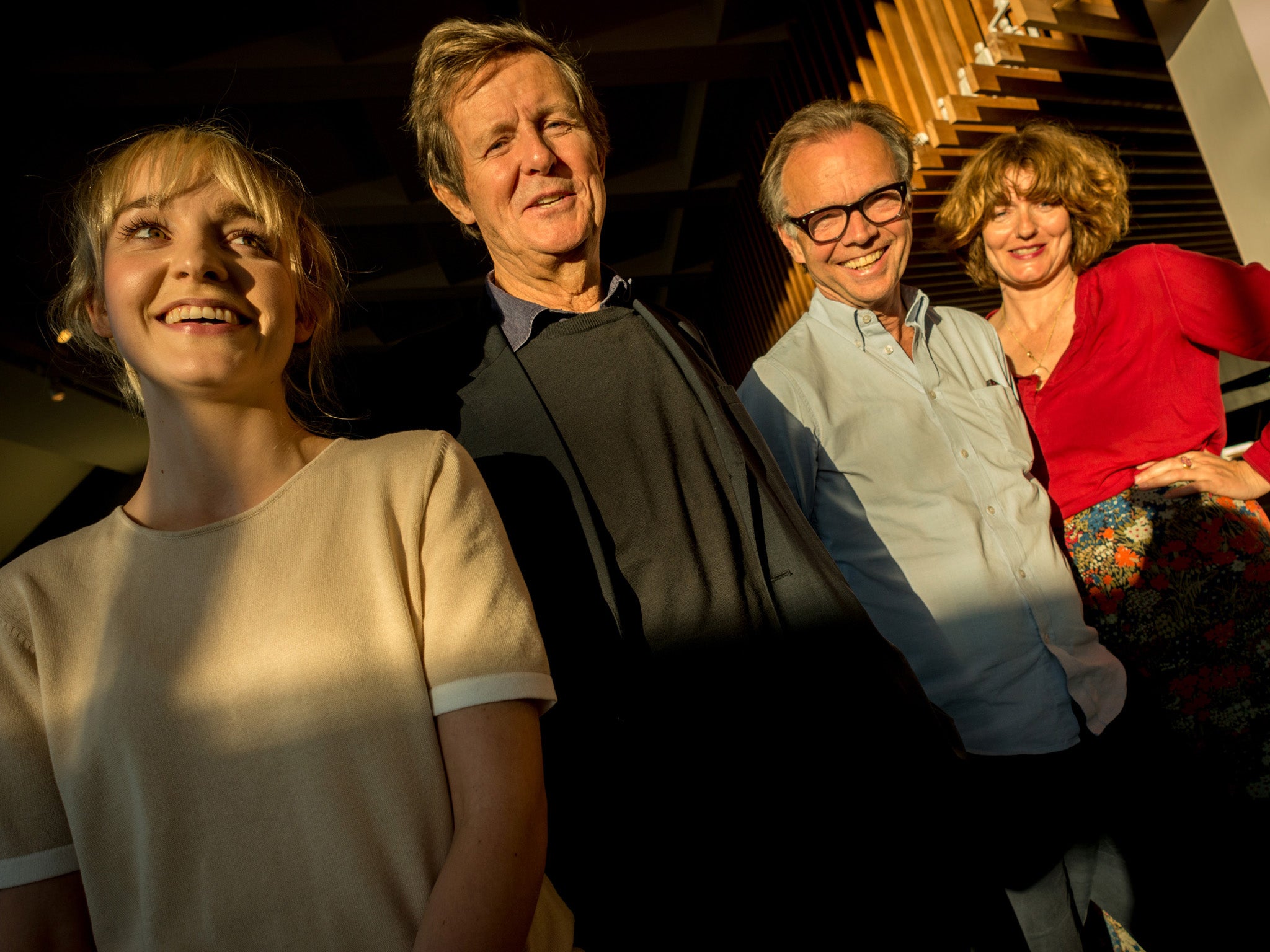

A new season of “Young Chekhov” at Chichester Festival Theatre presents two early, lesser-known works – Platonov and Ivanov – alongside The Seagull, all adapted by Hare and performed by an ensemble cast of 23.

“I’m on a lifelong campaign to persuade people that his romantic genius is as great as his classical genius,” says Hare with relish. “He was young and hot and romantic. My own preference is for those plays – I don’t think those later plays work so wonderfully on the stage. I know they’re meant to be great masterpieces but I’ve never seen a production of The Cherry Orchard that actually works …”

Platonov, written when Chekhov was about 20, is unlikely to be familiar to many – because it’s barely even a play, more an abandoned first draft. Hare first had a crack at it in 2001, but felt he failed to make it work; this new version cuts down seven hours of rambling material – “the speeches are just absolutely interminable” – to a brisk two-and-a-half hours.

Platonov is a Russian Don Juan, every woman in sight falling for him. But while there are familiar Chekhovian motifs here – an estate being sold off, a rural backwater, unrequited love – the overall tone is worlds away from what we expect. For a man famous for banishing melodrama from the 19th century stage, it’s totally melodramatic: there are bandits in the woods, a woman throwing herself across train tracks and a shooting. Plus, it’s farcically funny.

“Broad farce, sexual hysteria – it’s all about sex, it’s all about death, and it’s all about political anger. I think people will be amazed that that’s Chekhov,” says Hare. Meanwhile young Scottish actor James McArdle, playing Platonov, describes him as “a cross between James Dean and Basil Fawlty.” The mind boggles.

Jonathan Kent directed both Hare’s previous adaptations of Platonov and Ivanov – the script for the latter, first seen in 1997, is revived here with few changes – and explains it has been a “longstanding plot” to stage all three. “It is the birth of a playwright before the veil of his genius descended. It’s Chekhov naked.”

Ivanov, written in 1887, does at least resemble a play rather than juvenilia in need of Hare’s helping hand. You can see the progression: there’s still melodrama and farce, but Chekhovian tragedy begins to unfurl too, in the story of a depressed middle-aged man hoping to find salvation in the love of a young girl.

“Chekhov slowly begins to realise that he can suggest that everything in life is inevitable loss,” says Hare. “And by the time he writes The Seagull, it’s all about how they’re all hopeless victims of time. That makes The Seagull the most moving of the three.”

So moving, indeed, Hare confesses he’s just been in floods at the dress rehearsal. “I’m just a bubble of tears. I start crying at the beginning, because I know what’s going to happen to these young people! Maybe it’s because I’m an old man; the youth in the play is just absolutely unbearable.”

Written in 1895, The Seagull sees a young man, Konstantin, harbour ambitions as a writer while living in the shadow of his actress mother Arkadina; he’s in love with Nina, who dreams of becoming an actress, but is broken by an affair with an older writer. In Hare’s translation, the story reads clearer than ever as one about the struggle of youthful ambition in a world where a cynical older generation seems to be disinclined to share their good fortune – and as such, feels particularly pertinent today, when young people must struggle with mountains of debt, eye-watering rent, and unpaid internships, in pursuit of “creative” jobs fiercely guarded by older generations.

“Nina is the 20th century female – she isn’t just wanting to be a wife or a mother, she’s actively pursuing a career in the arts,” says Olivia Vinall, the young actress playing her. “In all of the plays there’s youthful exuberance coming up against people who’re experienced, going ‘it’s not going to work out for you …’ ”

“It’s very shocking, the pressure on the young people in The Seagull, and that’s true today too,” agrees Anna Chancellor. She plays the diva-ish Arkadina, another role that she says still rings true – although she insists she doesn’t know any actresses quite as ghastly as Arkadina. “He wrote Arkadina because he was so fed up with actresses he’d come across, and their demanding, divaish ways. So she’s a self-centred monster. But she’s got to be quite fun, otherwise she’s just a nightmare; you’ve got to want to be part of this woman’s party.”

The Seagull is the well-known, oft-performed conclusion of the trilogy – but Kent wanted to stage this work alongside Platonov and Ivanov to reveal a sense of progression. “So many of the themes are subliminally there, that all find their culmination in The Seagull – the first blossoming of his genius.”

It’s like eating a great big ice cream if you’re an adaptor, you just glut on it because it’s so gorgeous

Not that the world really needed a new version of The Seagull, Hare acknowledges: there are 25 in English already (he’s particularly a fan of Anya Reiss’s 2012 youthful, contemporary updating). But the trilogy needed a continuity of voice – and anyway, it was a joy to work on. “It’s like eating a great big ice cream if you’re an adaptor, you just glut on it because it’s so gorgeous.”

All three sound tartly modern, with Hare’s writing bringing out the wit more than the ennui. But they are staged in period, from the late 1800s for Platonov through to the early 1900s for The Seagull. The same deconstructed country house set is being used for all three; it opens up across the stage, with drawing room furniture giving way to trees and plants.

Although each play stands alone, there’s the option to watch all three on the same day, starting at 10.30am. It sounds daunting, but according to McArdle, “boxset” days are selling best. “There’s clearly an appetite for event theatre,” he says. “What’s quite special about this, is a cast being in rep. It’s just not done anymore, but I hope this way of working comes in to fashion again.”

It’s a sentiment echoed rather angrily by Hare (who has form here: his plays Racing Demon, Murmuring Judges and The Absence of War were triumphantly staged in sequence at the National in 1993). “They don’t have ensembles at the National Theatre anymore – bloody disgrace – we’re filling that gap. To see the joy of ensemble acting again is fantastic.”

As for the experience of sitting through that many hours of Chekhov? Hare is confident it will only enhance the plays, pointing to other theatrical marathons like Peter Brooks’ Mahabrata in 1985 or the RSC’s The Wars of the Roses in 1963. “I’m very much a binge man. Something special happens when an audience melts down – you cease to think about time. They’ve been my best days in the theatre. I love it.”

Platonov, Ivanov and The Seagull play at the Chichester Festival Theatre to 14 Nov; cft.org.uk

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments