Joe Orton: The life and crimes of a great playwright

Fifty years ago, Joe Orton and his partner were jailed for defacing library books. Now the dust jackets and the trial are being re-examined.

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Over the next fortnight, Islington Museum in north London is marking an obscure, quirky and subversive slice of British literary history. On 25 April, it will be 50 years since Joe Orton, the playwright best known for Loot, and his partner, Kenneth Halliwell, were arrested for stealing and defacing library books. With the total damage estimated at £450 (approximately 1,653 plates were removed from countless art books), Orton and Halliwell were sentenced to six months in prison, which they served later that year.

Islington Museum has begun its commemoration with Malicious Damage, an exhibition of the surviving 40 defaced dust jackets, which runs until 25 February. On 9 February, John Lahr, Orton's biographer and theatre critic of the New Yorker, will discuss Orton's life and work with the psychoanalyst Don Campbell. This weekend, Orton and Halliwell are being retried according to 21st-century sentencing guidelines.

The retrial is the brainchild of Greg Foxsmith, a criminal lawyer and Islington councillor. The case will be tried by genuine lawyers, the final verdict decided by a circuit judge. "I have always been intrigued by the case," says Foxsmith. "It's not unique, but it's certainly very unusual. The sentence appeared to me to be quite harsh."

Orton himself later explained the custodial sentence by claiming the judge knew that he and Halliwell were "queers". Due to the absence of trial transcripts, Foxsmith cannot prove whether homophobia did influence magistrate Harold Sturge. Instead, he concentrates on the legal differences between 2012 and 1962 – Foxsmith thinks they will be charged with theft, criminal damage and possibly a public order offence for their intent to shock.

Orton and Halliwell began stealing from local libraries in 1959. They were poor, unpublished and increasingly isolated from the world around them. The book stealing began as a cut-price way to let off steam and decorate their tiny flat into the bargain: almost all of the 1,653 art plates ended up as collages on the walls of 25 Noel Road.

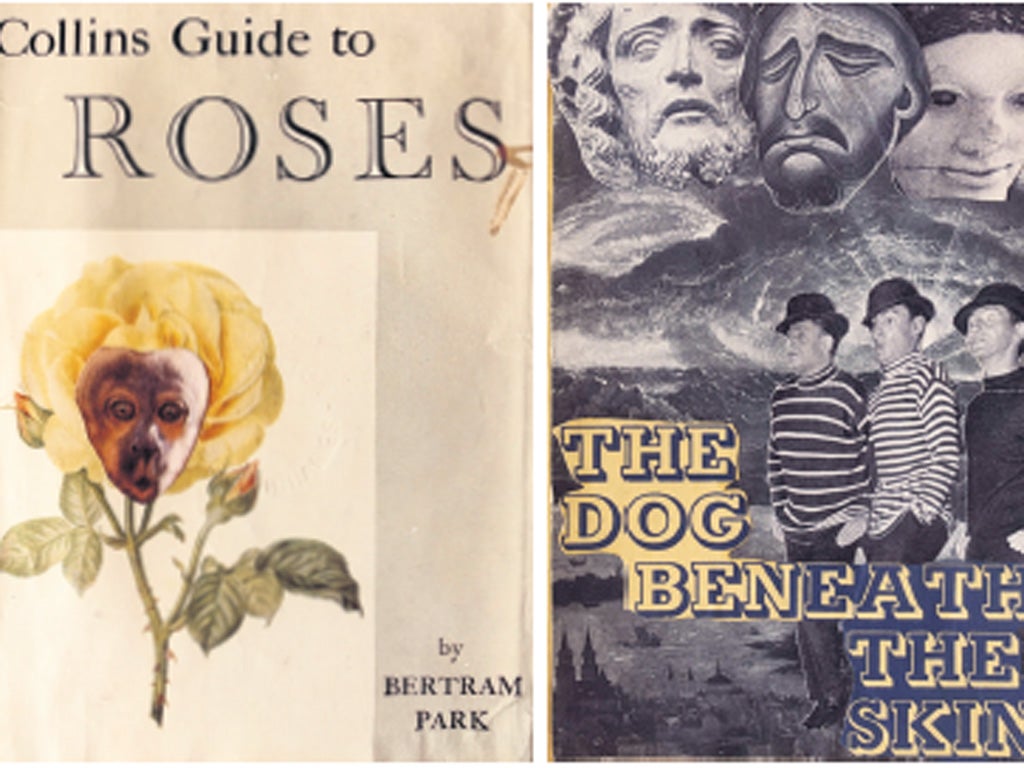

The remaining 72 stolen books (novels, plays, biographies and works of glorious obscurity like Selvarajan Yesudian's Yoga and Health) had their dust jackets re-designed in a lewdly comic fashion. A sober critical appreciation of John Betjeman was emblazoned with a near-naked, tattooed elderly gentleman. The only remaining part of the cover – JOHN BETJEMAN – stands out like a deadpan, and mildly sinister caption. The titles on the front of Emlyn Williams's Collected Plays were altered to create sexual innuendos: "Knickers Must Fall" and "Fucked by Monty". The exception is the seemingly innocuous "He Was Born Gray" – until it dawns that Williams's original was He Was Born Gay.

Ironically it was a tamer, if surreal effort – a gorilla's head affixed to a flower on Collins Guide to Roses – that provoked the greatest outrage at their trial. "A quite lovely book," the prosecuting barrister noted sadly.

Interviewed about the library affair in April 1967, Orton alternated between dismissing the vandalism as "just a joke", and elevating it into an act of literary and even political protest. "I didn't like libraries. I thought they spent far too much public money on rubbish."

Orton and Halliwell reserved particular derision for the pulp fiction that lined so many "rubbishy" library bookshelves. They pasted Agatha Christie's The Secret of Chimneys with giant cats. The plot of Dorothy L Sayers' Clouds of Witness was re-cast as the "enthralling" tale of "little Betty Macdree", interfered with by P.C. Brenda Coolidge. "READ THIS BEHIND CLOSED DOORS", the blurb warns. "And have a good shit while you are reading!"

John Lahr sympathises with Orton's self-proclaimed role as righteous protester against prudish mediocrity. "Orton wrote, 'Teach me to rage correctly.' He wanted to disturb people and make them see what utter rubbish they were reading. He delighted in irritating middlebrow people, whom he disdained."

Lahr detects anger, frustration and revenge in the comic assaults on the libraries, but adds that jealousy played a crucial role. "Orton and Halliwell were sensationally unsuccessful in their attempts to break into the literary game. Coupled with the defensive arrogance of the failed, I think it's pretty clear that their motive was envy at the 'rubbish' the library had on offer." Envy explains the choice of Auden and Isherwood's play, The Dog Beneath the Skin. A case of one unsuccessful collaboration between gay writers poking bitter fun at a rather more successful one?

By contrast, the 16 Shakespeare plays doctored by Orton and Halliwell reveal a genuine flair for book design: the plain covers of the Arden edition are embellished with beautiful or, in the case of Titus Andronicus, appropriately grotesque images.

But as Lahr also notes, Orton and Halliwell were mainly intent on dramatising an in-joke as public scandal. "They would hide and watch people look at their defacements. It was a piece of private theatre for their own amusement, but definitely staged." Sadly, no verifiable records of contemporary reactions exist. But Mark Aston, head of Islington's Local History Centre, hints that reactions were far from negative. "I have heard that librarians almost looked forward to the next instalment. It became a bit of a game. But after two and a half years, it had to end."

Their capture sounds worthy of an Orton farce. After a manhunt, in which policemen and librarians posed incognito, Orton and Halliwell were undone by Sydney Porrett, a clever but rather pompous member of Islington's legal department. A model perhaps for Loot's Inspector Truscott, he later pursued Orton and Halliwell through the civil courts, winning £262 in damages.

Prison marked a turning point for both Orton and Halliwell. Halliwell began the gradual slide into depression and violent self-pity that culminated when he murdered Orton in his sleep, before taking his own life.

For Orton, prison marked the end of obscurity and the beginning of fame. It was in prison that he discovered the authentic voice of his plays, the mixture of high style and low impulses. "I tried writing before I went into the nick. But it was no good," Orton said in 1964. "Being in the nick brought detachment to my writing. I wasn't involved anymore. And suddenly it worked." Lahr agrees. "He didn't care anymore about people's judgment. He had gone beyond shame. He had nothing to lose. And when you have nothing to lose you're dangerous."

The 40 defaced library books continue to divide opinion. Foxsmith sees them as evidence in a trial rather than works of art. Aston is proud of the collection, if slightly disapproving of its creation, and accepts the irony of the library's exhibition with good cheer. Lahr sees Orton and Halliwell's use of collage as ahead of their time. "We live in a world of collage. What is a remix but a collage?"

Whatever their worth, the 40 remaining dust jackets do prove one thing. You really never should judge a book by its cover.

Orton and Halliwell's retrial and John Lahr's talk are part of Islington's LGBT History Month

Malicious Damage, Islington Museum, London N1 (www.islington. gov.uk) to 25 February

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments