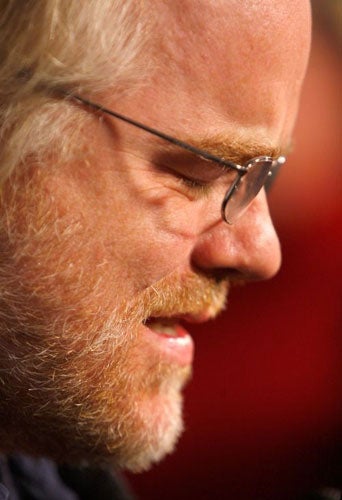

Heavy hitter: Philip Seymor Hoffman

He conforms to few notions of what a Hollywood leading man should be like. But no actor has a more compelling presence, and now London has the chance to see him make his mark as a director for the stage

Your support helps us to tell the story

This election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

For A man who is in London to direct a play, and won't even be appearing on stage himself, it's remarkable how much of the attention aimed at Philip Seymour Hoffman focuses on his physicality. He's here for the European premiere of Riflemind, a play by Cate Blanchett's husband Andrew Upton, which opened this week. But that extraordinary screen presence is hard to dispel even when he's working behind the scenes.

Of the many throwaway epithets attached to Hoffman, "doughy" is surely the least appropriate. It's frequently applied by critics seeking to emphasise how extraordinarily vulnerable Hoffman can seem on screen, how he casts all affectation aside to play every part with a naked honesty that rejects mannerism as cheating. And sometimes, since Hoffman is heavily built, that means we are reminded that some of the people he plays are not exactly at their physical peak. But "doughy"? As an artist, Hoffman is anything but doughy. The sense of the man that sticks with most moviegoers when they leave the cinema is not of a slothful weight. It's of a performer who is nimble, lean and obsessively precise.

To such shorthands, the 41-year-old Hoffman offers his own alternative. "A lot of people describe me as chubby or stocky, which seems so easy, so first choice," he once said. "There are so many other choices. How about dense?"

Dense: that's it. For all his size, Hoffman always feels like a coiled spring. "He's never not concentrated," says John Lahr, biographer and drama critic at The New Yorker. "He's extraordinary. He's completely compelling to watch. And everything he does illuminates character."

There are few who would demur from that judgement of Hoffman the actor: he has taken the baton from Kevin Spacey as the acceptable face of serious, unostentatious acting in Hollywood, and like Spacey has been drawn to directing in London.

In films big and small he has turned in a string of impeccable performances, from his creepy phone-sex addict in 1999's Happiness to the ferocious blackmailing elder brother in last year's Before the Devil Knows You're Dead. Put in charge of a project, however, and his credentials are more in doubt. "As an actor, he's really peerless," says Lahr. "But I think that as a director, he's less rigorous with other people's talent than he is with his own."

For Riflemind, the notices have been distinctly lukewarm. The reviews came out yesterday, and by and large they dismissed the play, which is about a rock band that re-forms and attempts to make a comeback. It's a "listless" production, wrote this newspaper's critic, Paul Taylor. "It's theatrical suicide," was the verdict of Charles Spencer in The Daily Telegraph. Such brutality was spread across the press.

For someone like Hoffman, as particular about his professional reception as other A-list stars are about their hair, such disparagement will hurt far more than remarks about his size. "I know I'm not as handsome as some of the other guys," he says. "But I'm OK with that... if you're truly vain you care more about your work than how you look in your work. I actually consider myself a pretty vain guy when it comes to that."

Hoffman's ferocious concern for the quality of his work belies his route into acting, which was more or less an accident. A keen wrestler as a teenager growing up in Rochester, New York, an injury put an end to his athletic activities. Searching for an alternative, he says, "I tried out for a play, and there were some cute girls there, and that was basically it." (Unfortunately, the chief object of his affections turned out to be more interested in his brother.) Around the same, Hoffman's mother, a lawyer, took him to the theatre, and the former athlete was hooked. "I couldn't believe that people were making me believe something in front of my eyes," he said later. "It didn't make any sense. It was a miracle. When theatre does it, there's nothing better."

A few years later, he studied drama at New York University's Tisch School of the Arts. "I never thought I'd do films," he says. "I was studying theatre, and my dreams were about riding my bike to the theatre on Sunday afternoons to do a play, and they still are." But Hoffman's intense, uncompromising personality, such a boon as a performer, had a dark side. Shortly after leaving Tisch, Hoffman checked into rehab for addiction to alcohol and pills. Now clean, his work is nevertheless still informed by those years. "It was a long time ago, so it's not like I'm sat there going, 'Well, when I was in rehab...'" he told the London Evening Standard earlier this week. "But I bring my experiences along."

In the early 1990s he combined theatrical work with moonlighting as a waiter and a lifeguard to make ends meet; before long, though, he found himself a niche in Hollywood. In 1993, he turned in a breakthrough performance in Scent of a Woman, in a cast led by Al Pacino, and he put his theatrical ambitions on hold.

Hoffman developed a respectable body of work as a character actor, but his chances were always limited to the fringes, with his best-known role before 1997 being a turn as a tornado-chasing scientist called Dusty in Twister. Then Paul Thomas Anderson cast him in Boogie Nights, his cult tale of the Californian porn industry in the early 1970s and everything changed. As Scotty, a member of the film crew who nurses an abiding passion for the industry's biggest star, Dirk Diggler, Hoffman was pathetic, physically unappealing, and extraordinary. A similar turn in Happiness followed a year later, and Hoffman had established himself as Hollywood's premier player of misfits and freaks.

Hoffman has, in the past, disputed that categorisation of the parts he plays. "Some people might struggle more than others," he told The Los Angeles Times in 2003, "and those people might be losers, but those are really just the characters who are more on the outside than others."

Hoffman continued to build a remarkable portfolio of outsiders in such films as Magnolia and Flawless, where he played a pre-op transsexual opposite Robert De Niro, and he seemed to be set for a successful career as a well-respected player of marginal figures in mainstream movies. But in 2005, Capote came along – and everything changed again.

If Boogie Nights had established him as a mainstream player, Capote was the film that put him in the big time. His version of the great American writer was rapturously acclaimed by critics and moviegoers alike, and he was one of the hottest favourites for the best actor Oscar for years. Hoffman, who is nearly six foot and has a deep, baritone voice, was uncannily good as the 5'3" falsetto-voiced Capote.

His preparation for the role involved months of sitting in a quiet room with director Bennett Miller "working out what the hell he is doing with his mouth and tongue and chin that makes him sound like that", and throughout the shoot he remained in character on camera and off. But the efforts paid off when, sure enough, Hoffman won the Oscar. Suddenly Hoffman was a legitimate A-list star.

That brought its own benefits, and since 2005 Hoffman's characters have covered a broader spectrum than the strict outsider figures to whom he was previously confined. But at the same time, Hoffman, an intensely private man who protects the privacy of his wife and two children jealously, was thrown by his new status. "Now, if someone looks at me it's 'cause they recognise me," he told the Standard, "whereas before, it probably just meant I had food on my face or something."

That, perhaps, is why Hoffman's interest in directing has grown: a desire to escape the highly egocentric strictures of the Hollywood mainstream. "Acting is an incredibly self-centred type of thing," he once said. I don't mean that in a bad way. It's one of the hazards... As a director, you don't have to become all caught up in yourself." And certainly those who have worked with him testify to the intensity of his interior process as a performer. The late Anthony Minghella, who directed Hoffman in Cold Mountain and The Talented Mr Ripley, said, "He is cursed by his own gnawing intelligence... he struggles for every moment in a film, overthinks, overanalyses, wrestles with the scene There are few actors more demanding in front of camera."

There are, Minghella also noted, few less demanding away from it. But as a director, that restless energy is released outwards. Working with him is "a headfuck", said John Hannah, a member of the Riflemind cast. He says Hoffman's vigorous style means that you have to brace yourself to work on a production with him for any length of time.

If Riflemind is less than wholly successful, then, perhaps the problem comes from the release of that dense energy that makes Hoffman one of the most compelling actors of his generation. Those who are disappointed by the London production can comfort themselves with the knowledge that they will soon be able to watch Hoffman again, with his collaboration with Charlie Kaufman, Synecdoche, New York just around the corner – about, ironically enough, a theatre director struggling with his work. The prospect is a mouthwatering one. "The only other actors who can do the things that he can are Dustin Hoffman and Al Pacino," says John Lahr. "He's got the same gift. And he's going to have the same career."

A life in brief

Born: 23 July 1967, Rochester, New York.

Family: Son of a lawyer and Xerox executive, he has two sisters and a brother. Lives with costume designer Mimi O'Donnell and their two children, with a third coming.

Early Life: Started acting in high school, attending theatre school in his summer holidays; went on to study drama at New York University, where he founded the Bullstoi Ensemble theatre company.

Career: A much lauded actor of stage and screen, his big break was in 1992's Scent of a Woman. Most noted for playing complex supporting roles in films including The Talented Mr Ripley and Almost Famous. Won the Best Actor Oscar for his portrayal of Truman Capote in Capote.

He Says: "My passion to develop as an actor didn't have anything to do with people knowing me. I had no idea that would happen. To become famous is something that I thought happened to other people."

They Say: "He is just not afraid to play all sides of the character, even the really creepy things that go on inside all our heads." John C Reilly

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments