New photography exhibition shows the tough reality of the now barely legal squatting movement

Squatting has withered since its 1970s heyday. As a historic show of photos opens in London, Charlie Gilmour wonders if the movement is ripe for reinvention in the new era of eviction, bedroom tax and homelessness

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.As a child, I dreamed of squatting. It was hearing second-hand stories about my biological father, Heathcote Williams, that did it. The Free Independent Republic of Frestonia, a chunk of West London that he and others attempted to secede from the United Kingdom in the late Seventies, sounded like the most exciting and glamorous thing in the world. They produced their own stamps, manufactured their own passports and declared a two-year-old to be the Minister for Education. More to the point, they held on to 1.8 acres of prime London real estate for years on end. You couldn’t get away with that today.

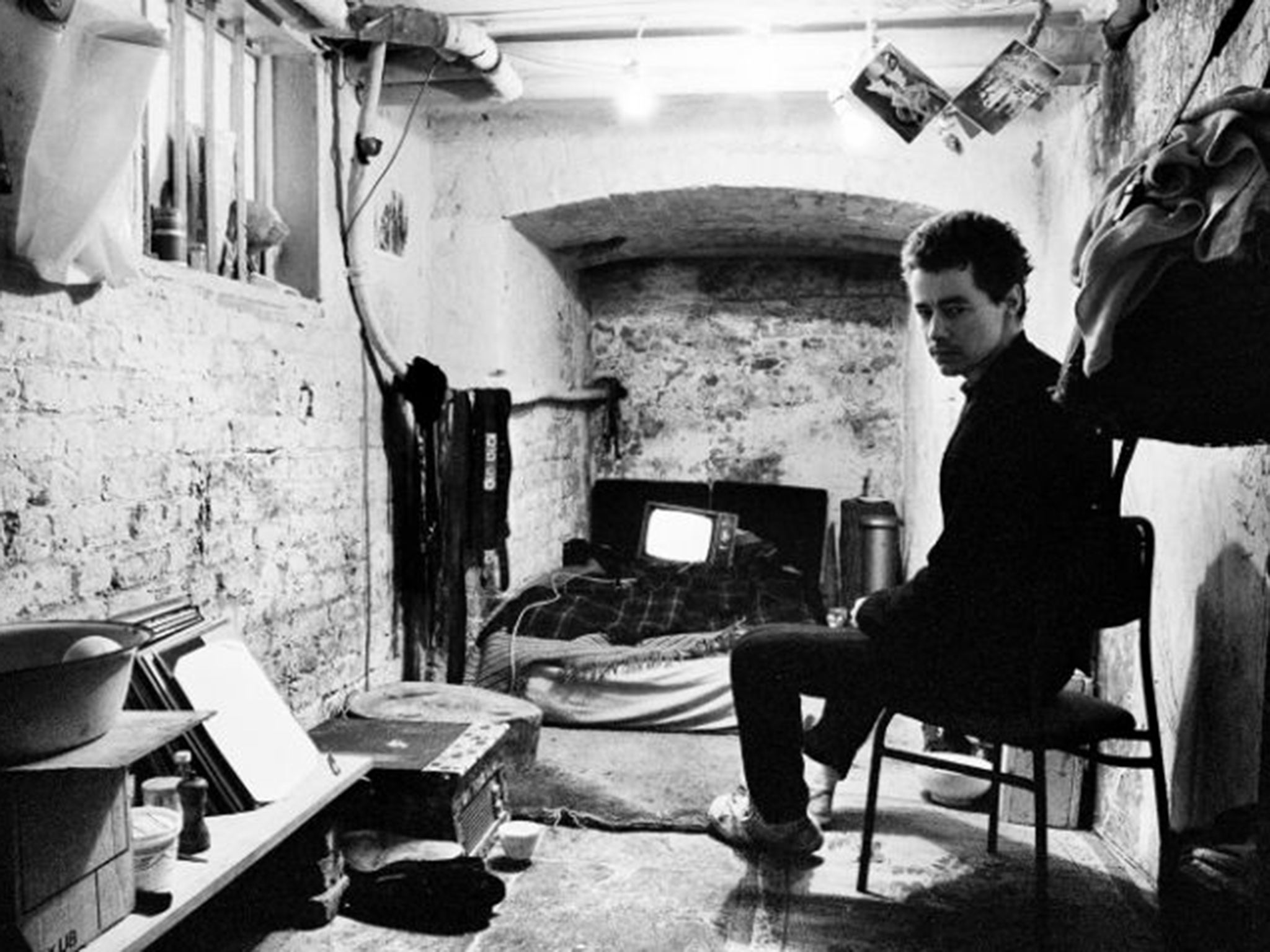

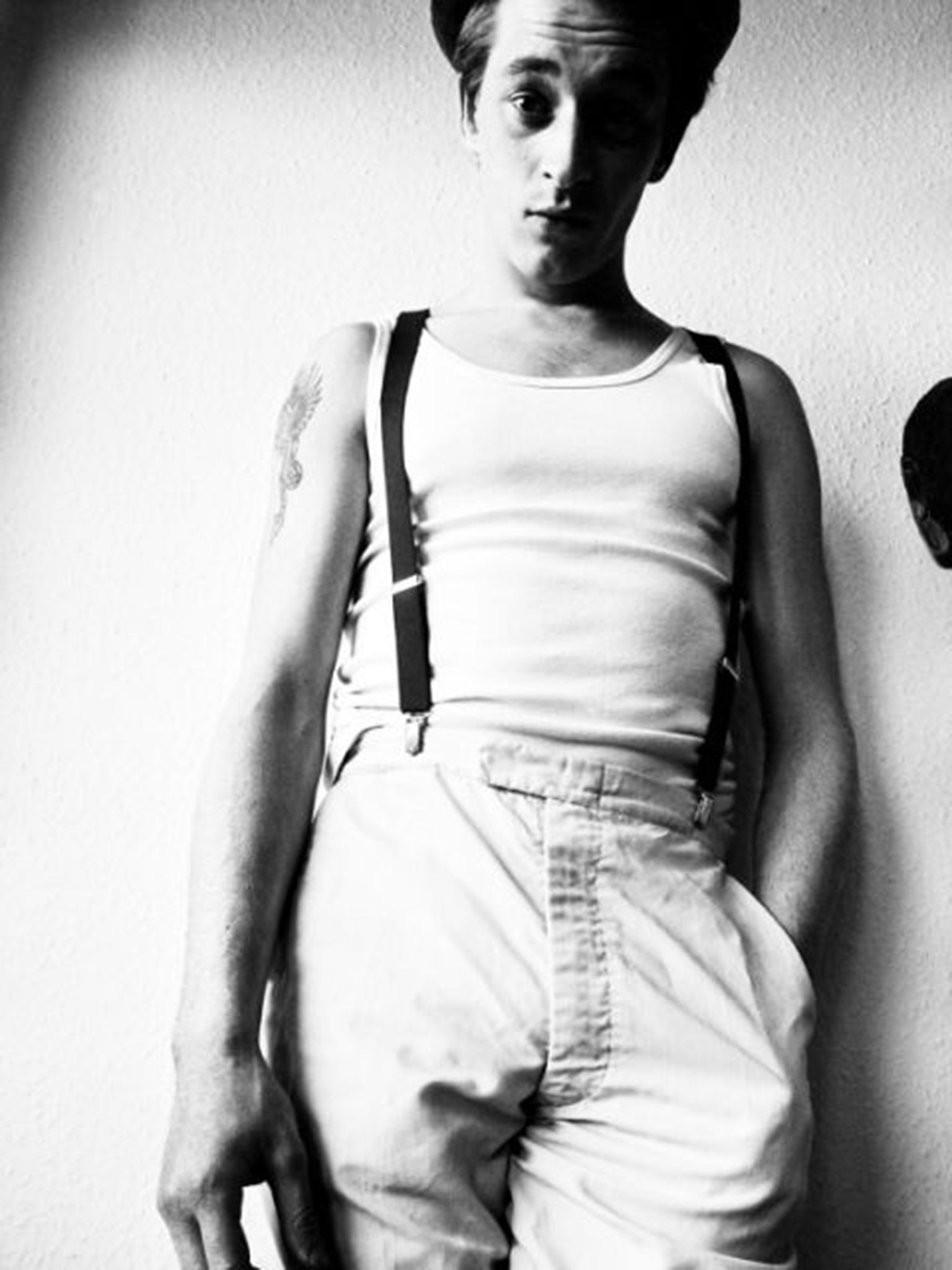

A recently unearthed treasure trove of images captured by painter-decorator, photographer and artist Mark Cawson – aka “Smiler” – provides a rare and intimate (at times painfully so) insight into what might be regarded as the golden age of squatting.

By the end of the 1970s, there were an estimated 30,000 squatters in London alone. When Cawson moved to the city in 1978 to attend Hornsey College of Art, joining their ranks was, he says, natural.

“It was just a way of life at that time,” he recalls. “There were a lot of empty properties around. Not having the funds or the wherewithal to go the normal route, I started doing it with fellow students Hornsey way, then ended up in a huge ex-blind hospital in Muswell Hill. It was an extraordinary place.”

Thanks to aborted redevelopment schemes – delayed by tough economic times – whole streets were left abandoned, so if you had a crowbar, you had a home – and London in the 1970s was a land of opportunity. Piers Corbyn, weather forecaster, housing activist and brother of Jeremy, remembers it well:

“It was an amazing time. We had 600 squats around us in the area of Elgin Avenue alone. We squatted numbers 9-51. There were hundreds of us. The legality was that if you gained entry without breaking and entering then you couldn’t be arrested for anything, and you couldn’t be removed without a court order,” says Corbyn, who, at 68, gleefully celebrated his most recent birthday in a squatted council redevelopment office.

And squatters were heroes as well as mischief-makers. Tony Allen, considered by many to be the father of alternative comedy, helped set up the Ruff Tuff Cream Puff Estate Agency, which over the decade matched 3,000 homeless people with empty homes.

“We broke into places and we gave them to people, basically,” says Allen. (While breaking and entering was illegal, it was almost impossible for the police to prove.) “We were just helping people have somewhere to live,” he says. “Everybody loves this idea of owning their own property and having a mortgage – but that’s a death debt. If everybody’s tied to maintaining the mortgage and maintaining the property, they’re fucked. They’re screwed. Then they need work. They need money. They need to obey the rules. Squatting liberates people.”

These pictures may suggest otherwise. But actually, squats came in all sizes. Some were mattresses-on-the-floor affairs, some cosy family homes, where the occupiers lived by the rules, paying utilities and council tax. Still, not all were so saintly. “A couple of buildings got quite badly destroyed,” says KLF hit-maker, music industry executioner, and million-quid incinerator Jimmy Cauty, who lived rent free from 1977-1991.

“There was a house that we broke into in Clapham,” he remembers. “It was only a small two-up, two-down. We felt kind of cramped in it, so we started taking the walls out. Then we took out all the floors and ceilings as well. We ended up with just a huge open space with no internal anything. It took us weeks to do it. It was totally impractical. We had to build little sheds to sleep in.

“And obviously,” he continues, “if the building doesn’t actually belong to you, then you’re much more adventurous with what you do. The outside walls started bowing out because there was nothing to hold them in. Floors are integral to the structure of a building. I know that now.”

Cauty became something of a removals expert. “It was easy,” he says. “You only needed a crowbar.” He tried “five or six” places before finding his dream home, a building on Jeffreys Road, Stockwell, that eventually became known as “Trancentral”, the KLF’s quasi-mythical base of operations.

But life was not always a jolly game of anarchist Monopoly. That the Cawson archive has come to light is, in itself, something of a miracle. Half the people in the pictures, he recalls, are dead.

“Or if they’re not dead,” he says, “I’ve never seen them again. At that time, London had become flooded with Iranian heroin after the Revolution, which had a big impact. As did Margaret Thatcher and Aids.”

Cawson was not entirely untouched by the chaos that surrounded him. “I did get my first shot of heroin in a squat,” he says, although he insists it wasn’t the lifestyle that was to blame. “I’d always experienced problems, way back to school days,” he says. “I’d never say that I was a fully functioning person.”

Indeed, after a lifetime of struggles, by the mid-2000s, Cawson was burnt out. Battling drug addiction, tuberculosis and lone parenthood, salvation came via a drug recovery programme, albeit in a rather unexpected way.

A chance conversation at an addiction meeting led to his pictures being seen by top photographer Gareth McConnell. Through him came a solo show, now at the ICA. “It’s really given me a new lease of life,” says Cawson, who, after decades of neglect, has picked up his camera once more.

Back on the streets, he’ll find life on the edge is sharper than ever. In London, the number of rough sleepers has increased by 79 per cent since David Cameron came to power in 2010. Many others are only a payslip away: according to the English Housing Survey, private tenants in the city are handing over an average 72 per cent of their income for rent.

And it’s not just landlords who are raking it in. Bailiffs are making a killing too. Thanks, largely, to rising rents, the bedroom tax, and cuts to housing benefit, tenants are being booted out of their homes at the highest rate since records began.

In London, the number of rough sleepers has increased by 79 per cent since David Cameron came to power.

The picture is clear. As capital floods into the city, so the people are being flushed out. Figures obtained by The Independent this year revealed that homeless families are being moved out of their local boroughs, often out of the city entirely, at a rate of 500 per week. If ever Londoners needed an alternative to the violence of the housing market, it’s now.

Unfortunately, Tony Allen’s old tag – “Squat Now While Stocks Last” – has turned out to be horribly prescient. Squatting is harder than ever. Not that there’s any shortage of houses. According to a recent report published by the Empty Homes Agency, there are 600,000 empty houses in the UK; 22,000 of them are in London alone. But since 2012, recycling these spaces has become an offence punishable with six months in prison, a £5,000 fine or both.

Non-residential properties can still be squatted, until eviction papers arrive from the courts. But activists claim the law against squatting residential buildings – brainchild of the former Conservative MP Mike Weatherley – has even killed. In February 2013, 35-year-old Daniel Gauntlett, a homeless father of two, was found frozen to death on the doorstep of an empty bungalow in Kent. To enter the house would have been a crime and, according to Squatters Action for Secure Homes (Squash), the new law was “the nail in Daniel’s coffin”.

It’s tragic, but hardly surprising. According to data gathered by Squash, there is a “noticeable and significant” rise in the use of the new law during the winter months, demonstrating, they say, that the police are using it to “force homeless people out into the cold”. Evictions – never pleasant – have also, the campaigning group claims, become “more violent, aggressive and dangerous, especially now that squatters are commonly viewed as ‘criminals’”.

“There’s been a lot more violence against men, women and children from squats,” says Phoenix Rainbow, an activist who has been on the scene for more than 20 years. “There’s men breaking in and dragging people out by the hair. It’s created a lot of prejudice against squatters.”

And while it is not illegal to occupy empty commercial property – of which there is enough in the UK to create 420,000 homes – often, it has simply become too hot to handle.

“Thanks to the booming market, properties are more carefully watched,” says Simon, a recent graduate who started squatting when his job in the charity sector failed to match rent. “You’re lucky if you get a month.”

Some of Britain’s greatest cultural movements, from punk to rave, grew from these cracks in the city. Now that they’re being sealed up and cemented over, life is more about survival than art.

“Squatters have to spend all their time squatting,” says Jake, an activist in his late twenties who lives in an abandoned commercial property in east London. “If you’re getting evicted every month, you get in, you sort the building out, you get your papers, then you’ve got a week or two and you’re just looking for buildings because you know you’re going to get evicted. So it really can negate some of the political potential of the movement.”

Even outside of the city, utopia is hard to come by. Rainbow was there when the bailiffs came, with chainsaws and dogs, to clear Runnymede Eco Village from its squatted plot of land in Surrey last month.

“They had a big team of bailiffs just going through from one end to the other, chainsawing things and smashing things up,” says Rainbow. “It was an incredible community. There was everything: from an Anglo-Saxon longhouse that we built, through to proper old-style Celtic roundhouses, octagon-shaped houses, shacks made out of pallets and wood, a teepee powered by solar panels… It was just old fridges and bicycles and cans and broken glass when we got there three years ago.”

Despite it all, Rainbow sees sunshine through the storm. “It’s been very hard for squatting in the last few years but there is a vast wave of push-back,” he says. “There’s a massive housing movement building. A tidal wave is coming.”

In some parts, it has reached land. Across London, squatters and tenants have been forming alliances against councils and developers. Indeed, as development blight continues to uproot communities – renters and squatters alike – it’s becoming hard to tell one group from the other. Even legal squatting has become a political act.

Focus E15 – a group of young mothers living in a homeless hostel in Newham – rose to fame this time last year when, rather than allowing themselves to be evicted and sent as far away from their families and friends as Manchester, they occupied a disused block of flats on the nearby Carpenters estate. Embarrassed by the media attention, Newham Council eventually agreed to house 40 people on the estate. “This,” said founders Jasmine Stone and Sam Middleton at the time, “is the beginning of the end of the housing crisis.”

More recently, at Sweets Way, an estate in north London, activists and squatters fought alongside social and private tenants down to the very last man. As in so many of these cases, residents were being evicted en masse to allow the owners – Annington Homes in this instance – to redevelop the site.

“The whole estate was covered in piles of people’s belongings they couldn’t bring with them,” says Liam, an activist who was there from the start. The few remaining families were, he says, “scared and demoralised”.

“All we did as activists was raise the sense of possibility,” says Liam. “I told some stories from Focus E15 and the work we’d done in Newham and it was like things just flipped. A group of about 20 residents went right across the road to Barnet Homes and blockaded the front of the office that day and all managed to get slotted in for meetings with senior staff that afternoon. I was utterly blown away by it. People just became so militant about it so quickly.”

The occupation that followed lasted more than six months and the end, when it finally came, threw the harshness of the housing market into stark relief. Social cleansing, as wheelchair-bound father of four Mostafa Aliverdipour discovered when High Court enforcement officers smashed in his windows and dragged him out of his flat, is no empty phrase.

“At the very least, every redevelopment project in London and maybe beyond is going to be thinking about the things that we’ve done when they put their next bids in,” says Liam. “The associated legal costs [for them] were in the tens if not the hundreds of thousands.

“As the housing crisis intensifies, the skills of squatters, such as eviction resistance, are going to become more and more important,” adds activist Jake. “Eviction resistance used to be the preserve of squatters, but evictions have been massively on the rise over the last few years. There’s been not only an obvious need but a desire from groups of residents to come together and start learning some of those skills from squatters.”

Their detractors would have you believe that squatters spend their days depriving people of their own homes. No mention of how often the opposite can be true. For – while much has changed since Smiler’s 1970s – squatting is now, as it always was, a simple response to a serious problem.

As Focus E15 puts it: “These homes need people. These people need homes.”

‘Smiler: Photographs of London by Mark Cawson’ is at the ICA until 29 November

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments