Has business deserted the arts?

A leading figure in the arts has called business leaders 'bastards'. Now the backlash has begun, says Simon Tait

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

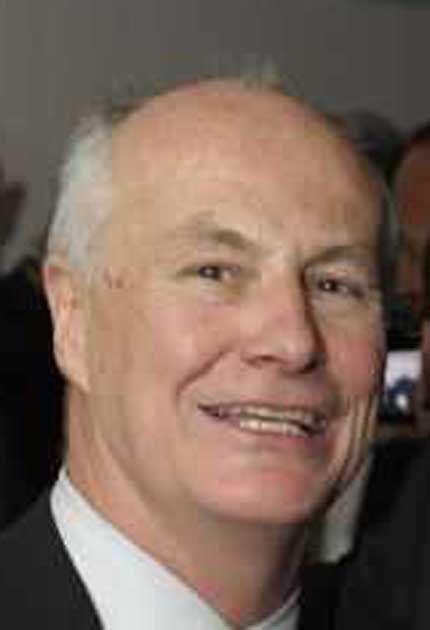

Your support makes all the difference.A few days before he left the Southbank Centre and these shores to return to his native Australia, Michael Lynch decided to pay off a final score. Known as The Crocodile, partly because of his uncompromising approach and partly for having been the casting director of the Crocodile Dundee movies in a previous life, he had had a universally acknowledged successful five years as chief executive in which he had completely reorganised the administration to ratchet up its efficiency.

His major triumph, though, was getting the Royal Festival Hall refurbished and reopened on time and somehow raising the £118m it needed, a cost which more than doubled in his time there. Yet, with some notable exceptions, he had done it without the help of the corporate sector, and in a farewell interview in the magazine Arts Industry he casually let a bomb drop.

"My greatest disappointment is that Corporate Britain didn't do themselves proud," he said, happily mixing his tenses. "At a moment when Corporate Britain were making more money than they'd ever made they were prepared to leave it to the individuals, the general public and the audiences of this place. And look at what the bastards have done to us over the last couple of years."

In a subsequent interview he singled out the investment bank Goldman Sachs for special mention.

Given the opprobrium heaped on bankers over the last few months Lynch's remarks might have seemed fair comment, but before the story had stretched its legs panic had gripped the arts community.

His successor at the Southbank, Alan Bishop, was hitting the phones to apologise to City contacts (each Goldman Sachs board member was individually called) and reassure them. The views of The Crocodile were not the Southbank's.

Nicholas Hytner, head of the Southbank's neighbour the National Theatre, felt constrained to say: "Contrary to Michael Lynch's experience ... the National Theatre continues to benefit enormously from the generosity of both corporate and individual City donors ... Goldman Sachs have been staunch supporters for 10 years ... "

Colin Tweedy, chief executive of the subsidised sponsorship agency Arts & Business, chose the conference at which the Arts Council announced a £40m lottery-fuelled recession safety net for arts organisations to declare: "Attacking wealth, bashing bankers, has to stop. Yes, there have been terrible mistakes, appalling bad practices, disgraceful greed, but business and individuals have no obligation to give ... "

But beneath the surface is a whole welter of issues which Lynch, perhaps unwittingly, has set alight. It is probably significant that neither the Arts Council nor the Culture Department chose to add comments to the Lynch backlash. It might be useful for arts subsidisers if the Treasury could be persuaded that business sponsorship of the arts was collapsing and a further hammering through the government grant would not go down well with a newly arts-conscious public.

Secondly, the "Armageddon" that A&B's Tweedy told the cultural sector to expect in January has not transpired, and it might not. Audiences for theatre, music and dance are holding up and museums and galleries are seeing more visitors than ever. Although corporate arts sponsorship has been declining in recent years, the contribution of individual donors has been rising in more than inverse proportion. While the latest figures show corporate contributions down 7 per cent, individual giving was up a staggering 25 per cent, so that overall sponsorship of the arts was actually up by 12 per cent.

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Thirdly, the Lynch remarks have not led to corporates deserting the arts, nor have their spokesmen put their heads above the parapet to comment themselves. Despite their difficulties, large-scale supporters such as UBS are maintaining their support. They are keeping their heads down because they like the arts' association with culture giving banks in particular a good image with customers and clients when other facets are less attractive; but saying so could nudge shareholders into demanding why money is being spent on art when their dividends are dwindling, the last debate the financial sector wants at this time.

Simon Tait is editor of 'Arts Industry'

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments