Why Loudon Wainwright is still going strong

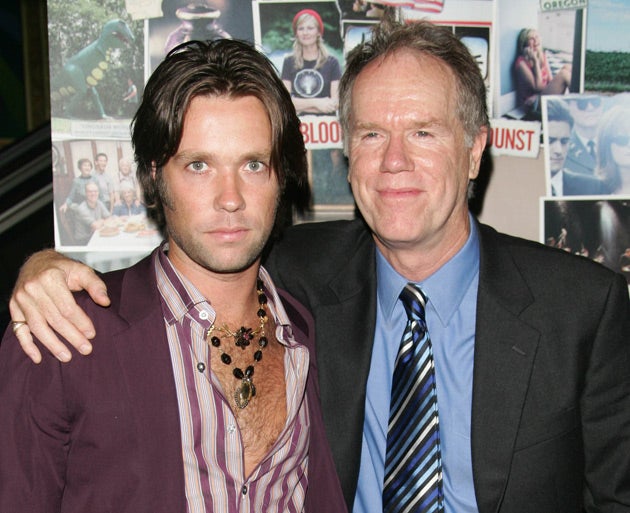

Father of Rufus and Martha, Loudon Wainwright III tells Andy Gill why he's still going strong. Just don't mention the skunk

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.There's a certain irony in the way that, even as the CD is gradually rendered redundant by downloading, the multiple-disc box set has become increasingly prominent. This is essentially a side-effect of the growth of the "classic rock" market of fiftysomething dads gazing wistfully at their heritage.

But why has there been no Loudon Wainwright III retrospective? Don't ask Wainwright – it's a mystery to him, and a source of some irritation. He's even compiled a running order, in case anyone's interested.

"I was working with Joe Henry, producer of my previous record Strange Weirdos, and moaning about the fact that I hadn't had a box set out yet," he explains. "So we were discussing what would be on it, and we came up with the idea that there would be three discs, and a bonus disc of me taking some of my old songs and re-recording them with this band of musicians we like to use. We shopped this idea around, and nobody seemed interested in the box set. But the idea of this bonus disc stuck; we still thought that was a good idea."

Hence Wainwright's new album Recovery, on which some of his choice songs are dusted down and made over by the songwriter and a crack band of LA session players.

The project gave Wainwright the chance to reassess his material, and the "blaspheming, booted, blue-jeaned baby boy" – as he described his youthful self in "School Days" – who wrote them.

"I can vaguely remember that guy," he reflects, "because that is one of the songs I have continued to perform. But a lot of them I hadn't, so I had to go back and relearn a few of them. And whenever I listen to that high, keening voice I used to have, I don't know if I like it. It's kind of an arresting vocal quality, and I think it got people to notice me at the time."

Wainwright's appearance in sleeve photos was also starkly at odds with the fashions of the day. Lee Friedlander's monochrome portrait on his debut suggests a certain asceticism; frankly, he looked like the guilty man in a police line-up. It was, he admits, a deliberate ploy: "I made a point of not being booted or blue-jeaned. When you start your career you have to figure out a way to separate yourself from the pack. So I went for a kind of preppy, psycho-killer look: I had short hair, grey flannel pants and a button-down shirt. I think it worked, because nobody else was looking that way at that time."

It worked enough for Wainwright to be heralded as the first "new Dylan". Though flattered, he found the accolade baffling. "I don't think of what I do as particularly Dylanesque," he once told me. "He was a mysterious, cryptic kind of songwriter, and mine are so clear, there's no mystery about what I'm writing about."

But his songs were marked by an intelligence and challenging attitude which, with his distinctive delivery and looks, secured Wainwright the cult appeal that sustains a long career. After two albums, his severity was supplanted by a more beaming, bearded visage that reflected the growing jocularity of his material. Like Leonard Cohen, he became a serious man seduced into comedy.

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

"What happened was that on the second album there were a couple of what you could call 'novelty songs' – 'Nice Jewish Girls' and 'Plane; Too'. Whenever I performed them, audiences would laugh. I found I enjoyed the laughter, so I moved in that direction. The third album had 'Dead Skunk' on it, which certainly changed my life. For a time, anyway."

"Dead Skunk", with its chorus, "Dead skunk in the middle of the road/ Stinking to high heaven", secured Wainwright his sole Top 20 hit, but the roadkill anthem became a millstone "in that people expected, and in some cases demanded, that I sing it". He rarely performs it now, and it is not on Recovery.

Re-recording his rather stark early songs with a sensitive band has in some cases altered their tone, reflecting changes in his own attitudes. The callow youth so sternly analysed in "School Days" is now regarded with something like wistful affection.

There's a certain irony to this, as when Wainwright first joined Atlantic Records, he strenuously resisted their attempts to record him with a backing band. On Recovery, however, he's found a band sympathetic enough to inhabit his songs intelligently and illuminate their themes, which in several cases reveal an perhaps unhealthy interest in growing old.

"As early as 1970, I was concerned about getting old. There's a kind of through-line in a lot of the material on the new record – lines like 'In Delaware when I was younger', 'If I was 16 again, I'd give my eye tooth', and a couple of others. So you can imagine how I feel about it now I'm 61."

These days, Wainwright spends much of his time working for film and television: his Strange Weirdos soundtrack for Judd Apatow's comedy Knocked Up was accompanied by the latest of several small acting roles, as an obstetrician – an echo of his role as Captain Calvin Spalding, the "singing surgeon", in three episodes of M*A*S*H – and he wrote songs for Jon Plowman's theatrical adaptation of Carl Hiaasen's Lucky You, which has been running at the Edinburgh Festival. In terms of music, though, you're much more likely to encounter the work of his offspring Rufus and Martha. Does this worry him, or give him a warm glow of parental satisfaction?

"I don't see it as a competition," he says. "Rufus and Martha are both really established now, and enjoying some success, and occasionally take me out to dinner... and pay! It's a rough business, so I worry about some aspects of it. But I'm pleased that they're in the family business."

And despite re-recording his old writer's-block lament "Muse Blues", Wainwright's not about to stop writing songs. "I've never really suffered complete and utter writer's block, really," he says. "I equate it with sex: in the beginning of my career, I was writing five songs a week; now, I occasionally write a song. But it's an exciting moment when it happens!"

'Recovery' is out now on Yep Roc; Andy Gill reviews it on page 19

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments